Stimela: The train and South Africa’s musical heritage

As politicians shake off the election season trauma of being stranded on the Metrorail, Percy Mabandu considers the train as a force that shaped South African music over the decades.

Author:

11 July 2019

Around 40 years ago, before Stimela even took on that name, the band was in Maputo, Mozambique, for a gig that became a disastrous fool’s errand. Stranded across the border with nothing but the clothes on their backs, some rags in their bags and a shoddy handle on the local language, they hustled a train ride home to Johannesburg. Years later, they remembered that train ride to name what would become an iconic South African musical phenomenon, Stimela.

Reaching out over the phone from Mbombela in Mpumalanga, the band’s founding drummer, Isaac Mca Mtshali, speaks with impish relish about that fateful train trip. Then, still known as The Cannibals, they arrived in Maputo to play a series of concerts organised by John Moriri and Reggie Msomi, a pair of enterprising musicians who dabbled as show promoters.

“First of all, our car broke down before we even got to Swaziland. Mind you, it was a Datsun sedan carrying seven band members with our instruments and luggage,” Mtshali remembers with howling laughter. “The gig was a flop. Now Moriri and Msomi had our passports and we didn’t have money. We were stuck!”

To make their way, they fought the promoters for their passports and pooled what little money they had. “We bought train tickets, but the money ran out just outside Maputo. So we sold our clothes, bought tickets, but that got us as far as Komatipoort. We had to find a place to sleep and make another plan.”

The tragicomic trauma and triumph of that rollercoaster railway ride stayed with them. It also led to them disbanding. However, the collapse of The Cannibals in 1979 saw the birth of Stimela.

Motif in motion: Stimela to Masekela

Towards the end of September, the band will play at the Standard Bank Joy of Jazz festival in Joburg. The gig is part of a grand promotional tour of their first record without Ray Chikapa Phiri. It’s a bold clawing at a life after the death of its best known lead singer and guitarist in 2017. The band’s new frontman, Sam Ndlovu, is looking at a long future still for Stimela.

“This band is like the thing it was named after. While some members climb off, others join in and the journey continues,” he says.

The late Hugh Masekela had his own take on the train motif. It produced his most epic song about the woes of working-class life during colonial apartheid.

Related article:

Masekela’s spectacular hit, Stimela (The Coaltrain), first appeared on his 1974 record, I’m Not Afraid. The tune is a monumental hymn that memorialises the journey and wretched lives of migrant workers conscripted to work in the mines of Johannesburg and Kimberley, of men and women ripped from their homes and lands across the South African subcontinent.

Few can claim never to have been moved by Masekela’s anthem: the opening staccato stagger of drumstick on cowbell; the steel-and-wood contraption mimicking the train as it churns and charges across the firmament: Dla-kah bla-kah, dla-kah bla-kah, dla-kah bla-kah, choo-chooo!

The rhythm is followed by a dramatic plunge into a bridge of silence before Masekela climbs out with details of his epic tale: “There is a train that comes from Namibia and Malawi. There is a train that comes from Zambia and Zimbabwe…”

It’s an ominous delineation of the dramas of economic displacement in all their dreaded glory. In Masekela’s languid libretto, the train is a cold and monstrous thing. He links it to the loss of land, home and livestock for the migrant mineworkers. By the time Masekela reaches for his horn to serve his melodic statement, the song begins to shore up the coal train as the handmaiden of the colonial assault. A lamentation!

A grand theme

The railroad-borne movement of the people is a grand theme in the work of Zim Ngqawana, too. The late jazz composer’s most ambitious opus, a three-part suite titled Amagoduka (Migrant Workers), is concerned with the transformative power of the rails on the personhood of migrant workers.

The composition first appeared on the album San Song in 1996. The record is notable for being a second-generation collaboration between South African and European musicians, almost 30 years after South African free jazz campaigners like Johnny Dyani, Dudu Pukwana and Mongezi Feza went into exile in the 1960s.

The record features a version of Ngqawana’s suite unfolding as a series of transformative stations on the migrant worker’s path to becoming a being reborn. The Migrant Worker in his Homeland, The Migrant Worker on the Train and The Migrant Worker in Johannesburg are the three movements that make up the opus. Ngqawana later expanded it to include Migration to America on his 2008 recording with the University of Tennessee Faculty Ensemble, Zimology in Concert.

The sum of these parts is the boldest musical metaphor and monument yet by a musician to the train’s contribution to the making of modern South African reality. Each movement of the grand composition memorialises a notable moment of transformation.

The first movement is an invocation. A sonic depiction of the menacing energy that haunts the worker in his homeland. This energy, abjection by any other name, cajoles the unsettled man into migration, and so he elects to leave his home.

By the second movement, the listener is invited into the train carriage, the entombed site of a kind of eucharistic transubstantiation. In the hold of the train carriage, the old being dies, he is transformed and prepared for his rebirth before arriving at his mythologised urban destination.

The third movement marks the migrant worker in Johannesburg. The city in all its cold constitution. In Johannesburg, Ngqawana’s central character is woven into a new social fabric.

Through the lens

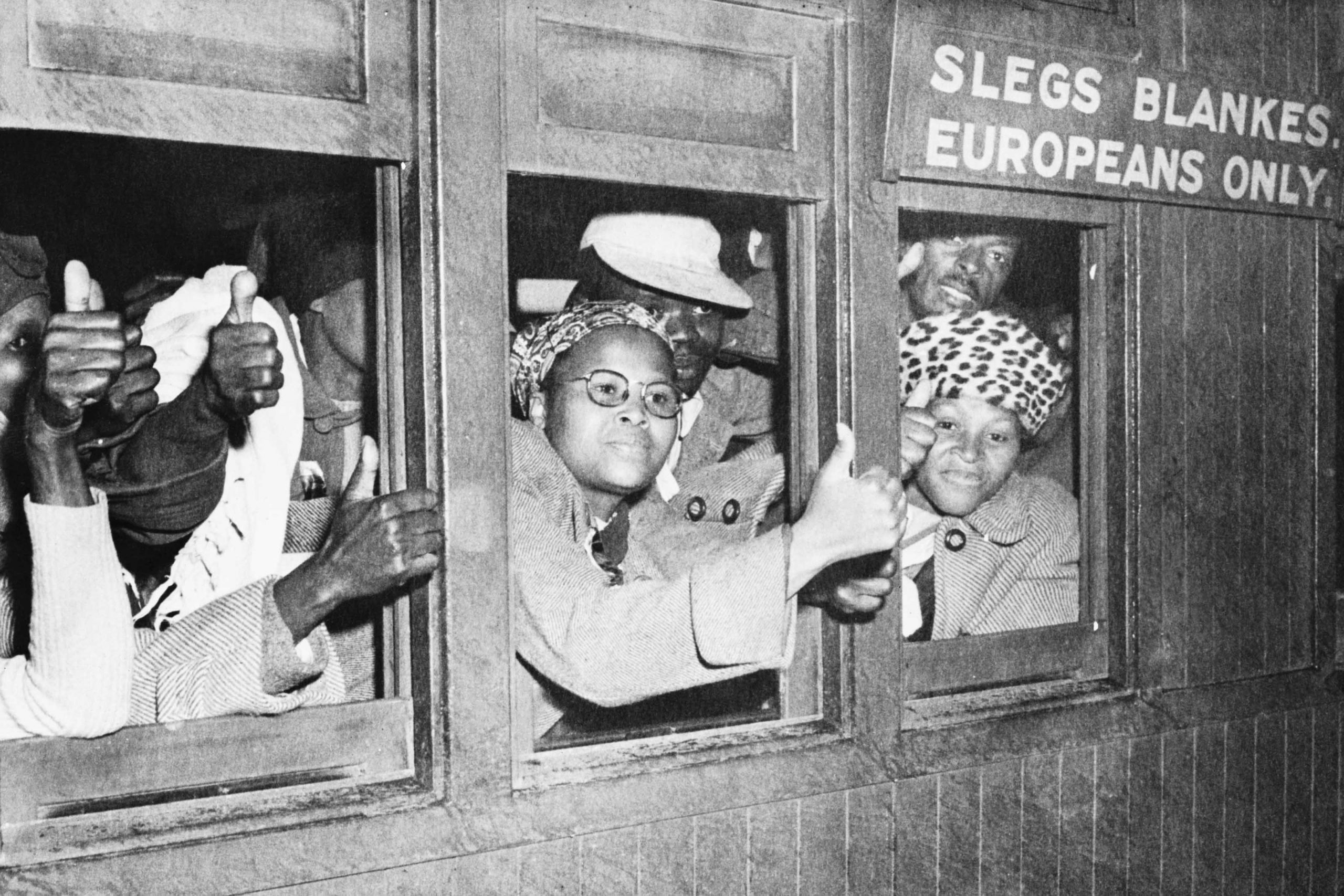

In photography, few have borne better witness to the feverish ferment of life in a train carriage than the late Ernest Cole. At his best, Cole turned his visceral lens on trains and helped shatter the veil of secrecy about black suffering during apartheid.

His 1967 book, House of Bondage, teems with revealing studies of the perilous lives of black working-class train commuters. His images of the crowded khushu-khushu, chockablock full of black bodies: sweaty, sombre and wading through their tragicomic social deaths.

Set to music, the pictures would sound like Bayete’s 1987 hit, Mbombela – an infectious ode to workers as lovers who carry their care and longing for their distant relatives like shovels and other tools. Bayete, led by Jabu Khanyile, garnered national acclaim with their song celebrating the chugging train, hurtling along with a pulse of diesel and steel.

Many musicians and creatives have followed since. Mbongeni Ngema’s runaway hit, S’timela Sase-Zola, is about a beloved woman as a joyous train. In gqom, gospel and other artistic fields, too, the train – coal, diesel or electric – remains a driving inspirational force for creating meaning.