Still rioting under Sly’s sun and stripes

Five decades after its release, Sly & the Family Stone’s ‘There Is a Riot Goin’ On remains confounding and inspiring in equal measure.

Author:

1 November 2021

Sly & the Family Stone’s There is a Riot Goin On, released in November 1971, is a work so powerful that we can still hear its echoes reverberating.

Sly Stone’s biographer, Jeff Kaliss, who published I Want to Take You Higher: The Life and Times of Sly Stone in 2008, argues that Riot, the shorthand for Stone’s album adopted by fans and critics, was “one of the most powerful and haunting albums to inspire the hip-hop movement”. Taking a look back at hip-hop history, he has a point.

From a sampling perspective, the songs Runnin’ Away, You Caught Me Smilin’ and Family Affair have been repurposed on A Tribe Called Quest’s Description of a Fool, J Dilla’s Jay Dee 8 and Ghostface Killah’s Dogs of War. And looking beyond Riot’s specific songs, the band’s music has been sampled by heavyweight rappers and crews that include NWA, Public Enemy, Big Daddy Kane, KRS-One, Missy Elliott, 2Pac, Dr Dre and Kendrick Lamar.

Related article:

Echoes of Riot could be detected strongly last year when the Los Angeles-based rapper Pink Siifu released a howling rage of an album titled Negro. Siifu’s album is an in-your-face expression of rage against white supremacist police murders and is a million miles from his 2018 album, Ensley, much like Riot represented a sea change from Sly & the Family Stone’s Stand!, their much-loved fourth album released in 1969.

As celebrated cultural critic Greil Marcus wrote in his book Mystery Train – Images of America in Rock ‘n’ Roll Music: “With Riot, Sly gave his audience, particularly his white audience, exactly what they didn’t want.” Marcus goes on to describe the album as “music that traps what you feel when you are shoved back into the corners of loneliness, where you really have to think about dead flesh and cannot play around with the satisfaction of myth”.

“It is not casual music and its demands are not casual,” writes Marcus. “It tended to force black musicians to reject it or live up to it.” These words could just as easily be applied to Negro, with both albums being what the world needs to hear, not what it wants to hear.

A disappearing dream

Having released Stand!, which delivered the band’s first number one single, Everyday People, Sly & the Family Stone were on the rise in April 1969.

As music critic Peter Shapiro wrote of Everyday People in Uncut magazine, “at a time when the civil rights coalition was breaking apart, when flower power was mutating into armed struggle, the Family Stone clung desperately to the belief that You Can Make It If You Try and had the gall to deliver the decade’s most powerful message of unity as a sing-song nursery rhyme”.

Shapiro points out that “the soaring mix of black and white voices made crossover seem like utopia”. But he also highlights the flip side of the coin, the album’s Don’t Call Me Nigger, Whitey!, which he describes as the sound of the 1960s dream disintegrating before Stone’s eyes.

Related article:

A mere seven months after the release of Stand!, Stone’s optimism had completely disappeared. He stood before a Bay Area audience in San Francisco and cried out: “You’re over. You thought you were cool, but your arrogance was your undoing and San Francisco is now officially over.”

The second half of the 1960s had been dominated by riots in cities like New York, Los Angeles, Detroit and New Jersey and the assassinations of Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr and Bobby Kennedy. Just months after Stone uttered these words, the National Guard would open fire on unarmed students protesting against the Vietnam War at Kent State University in Ohio.

In his book Funk – The Music, the People, and the Rhythm of the One, Rickey Vincent argues that by the early 1970s most politicians and activists had been “killed or co-opted”, and what followed was a decade of “no protests” and “no leaders”. Many decades later, Stone would provide Kaliss with some insight into his state of mind back in 1969 and 1970.

Related article:

Stone told him that he wasn’t prepared to be the audience’s shining star anymore. “Everybody’s gotta be a role model, either everybody or nobody,” he said. The quote has echoes of Bob Dylan’s 1965 single, Subterranean Homesick Blues, with its infamous line, “Don’t follow leaders, watch the parkin’ meters”.

Marcus writes in Mystery Train that Riot, the album that would follow Stand!, emerged “out of a pervasive sense, at once public and personal, that the good ideas of the sixties had gone to their limits, turned back upon themselves, and produced evil where only good was expected”. He describes Riot as an “exploration of and a pronouncement on the state of the nation, Sly’s career, his audience, black music, black politics and a white world”.

The evolution of Thank You

Between mid-1969 and the release of Riot in November 1971, Sly & the Family Stone only issued one single – Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin), which arrived in December 1969. If there was ever a hint as to what Stone was about to deliver with Riot, this single was it. Delivered over an addictive funk riff, the song’s lyrics explored a darker vision than the band was known for, acting as Stone’s declaration that he could no longer go on pretending.

Thank You drips in urban tension and provides a disturbing vision of the fall of the 1960s dream: “Youth and truth are makin’ love/ Dig it for a starter/ Dyin’ young is hard to take/ Sellin’ out is harder.”

As Stone’s world view darkened, his dalliances with drugs, primarily cocaine and PCP, had spiralled out of control to the point that wherever he went, a violin case of drugs followed.

As Sly & the Family Stone saxophonist Jerry Martini explained to San Francisco music journalist Joel Selvin, a normal day entailed that you “wake up, take Placidyl [a sedative developed by Pfizer in the 1950s], which Sly got from his doctor, then you snort enough cocaine until you can’t talk straight”.

Related article:

It was into this world that There Is a Riot Goin’ On was born, its title an answer to Marvin Gaye’s question, What’s Going On, asked just five months before.

On the album, the single Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin) had evolved into the even more menacing Thank You for Talkin’ to Me Africa, with the same song delivered over a much slower deep groove with muted psychedelic vocals dripping in reverb.

The fear and pain is palpable as Stone sings: “Lookin’ at the devil/ Grinnin’ at his gun/ Fingers start shakin’/ I begin to run/ Bullets start chasin’/ I begin to stop/ We begin to tussle/ I was on top.”

As music critic Matthew Greenwald writes: “The closing track on There’s a Riot Goin’ On is perhaps the most frightening recording from the dawn of the 1970s, capturing all of the drama, ennui and hedonism of the decade to come with almost a clairvoyant feel.”

Brutally honest

The duality that inhabits Riot, the disintegration of the 1960 dream and the downward spiral of Stone himself are poignantly captured. As much as Riot is a laceration of the failed dreams of the era, Stone is not beyond turning his pen on himself.

The album’s opening song, Luv & Height, a down-and-dirty funk song with the lyrics “Feel so good inside myself, don’t want to move/ Feel so good inside myself, don’t need to move”, is almost a fly-on-the-wall image of the album’s creation, with Sly recording most of it high in bed in the Bel Air mansion he called home.

On Runnin’ Away he sings, “Running away to get away/ Ha-ha, ha-ha/ You’re wearing out your shoes/ Look at you fooling you”, a line that feels like he is speaking directly to himself.

Related article:

The song Brave & Strong contains the lyrics “Frightened faces to the wall/ Oh, can’t you hear your mama call?” and later “Out and down, ain’t got a friend / You don’t know who turned you in”. That these two lines speak both directly to white violence and the life of a drug addict is a perfect example of Stone’s genius.

On the following song, (You Caught Me) Smilin’, Stone confesses to the audience how the drug abuse is a mask for the pain he finds himself in, until for a second the mask slips: “You caught me smilin’ again/ You caught me smilin’ again/ Hangin’ loose/ ‘Cause you ain’t used to seeing me turnin’ on, ha ha.”

It’s a dark window into Stone’s world that is delivered over a sparse, upbeat funk rhythm that feels unsettling and too murky and boisterous for its own good, like most of Riot, which emerges like a dark, narcotic, psychedelic-funk nightmare.

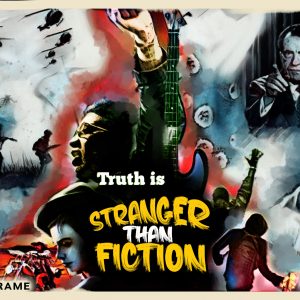

A visual legacy

As much as we are still hearing the influence of Riot in other music, we are still seeing it too. Riot’s album cover, a redesigned version of the American flag, the Stars and Stripes, has become a visual reference over the years. Just three examples from the past two decades are The Avalanches’ cover for Wildflower, OutKast’s for Stankonia or Pink Siifu’s for Negro.

Sly & the Family Stone’s flag was suns and stripes and the flag’s blue background was replaced by black. As Stone explained in 1997 to Jonathan Dakss, a web technician for the band’s official website: “I wanted the flag to truly represent people of all colours. I wanted suns instead of stars because stars to me imply searching, like you search for your star and there are already too many stars in this world.” It is a sentiment that chimes perfectly with Stone’s refusal to be held up as a star by his audience.

Related article:

It’s clear that 50 years on from the release of There is a Riot Goin’ On, Stone’s masterpiece has lost none of its power. It is no wonder that Afro-futurist funk innovator George Clinton, famous for his own cosmic brand of funk, refers to Stone as the only other person to emerge from the metaphorical spaceship in which Clinton claims to have arrived on Earth.