Squid Game, Kafka and the horror of daily life

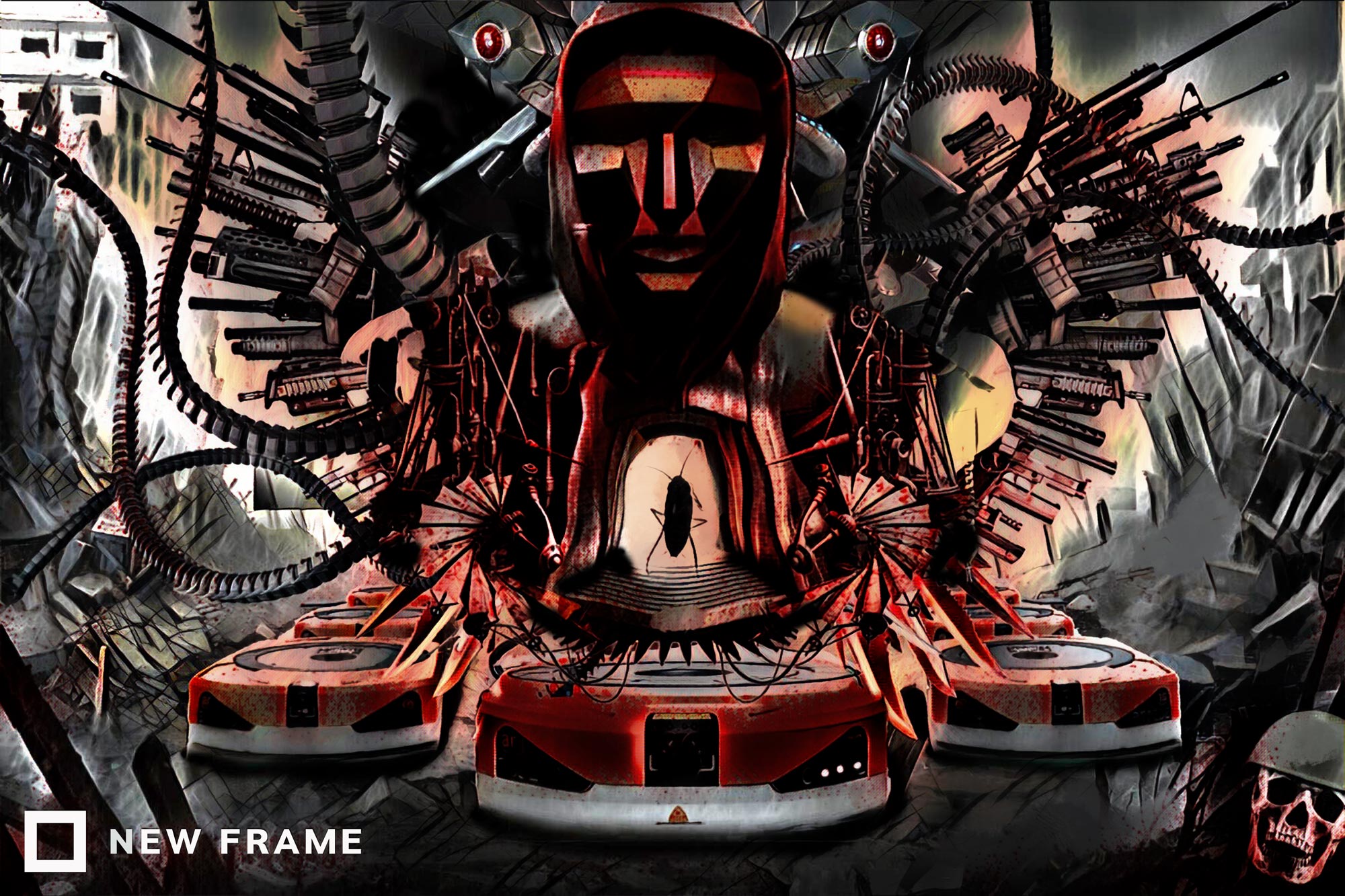

The popularity of shows like Squid Game suggests the horror genre is moving away from depicting the supernatural towards a critique of the cruelty of capitalism’s power over our everyday lives.

Author:

27 October 2021

As a genre, horror has long been a medium for hard-hitting social critique. Whether in the form of Jordan Peele’s macabre vision of racism in Get Out (2017) or the sadistic late capitalism of Squid Game (2021), horror can expose the absurdity and perversity latent in everyday life.

The themes that horror explores reflect the larger political and economic landscape, interpreted through the fears and nightmares that dominate us. For example, the shock of the industrial revolution, which transformed human life in the 19th century by introducing rapid technological shifts, wage labour and consumer capitalism was echoed in the gothic horror depicting haunted castles and monstrous aristocrats.

In his book Wasteland: The Great War and the Origins of Modern Horror, cultural historian W Scott Poole argues that the modern horror genre was born in the chaos of World War I. From 1914 to 1918, new forms of industrial warfare butchered millions of soldiers and civilians in Europe, Africa and Asia. From lethal gas attacks to aerial bombing, cutting-edge technology was deployed for the single purpose of causing mass carnage at a scale that exceeded all the wars, colonial invasions and state violence that preceded it.

Related article:

World War I destroyed the then common belief that society was becoming more peaceful. This created a cultural shift. Horror artists began to move away from depicting supernatural threats to exploring instead the real-life terror of how human-created machines and social institutions became mechanisms for mass dehumanisation. This included both horrifying tales, but also the dark comedy and grotesque satire used by visual artists associated with radical movements like Dadaism and surrealism.

One of the most influential mappers of these “nightmare lands” was the German-Jewish writer Franz Kafka. While Kafka is not generally cited as a horror author, Poole argues that his “themes of alienation, ruin, torture and madness” have exerted a huge influence on the modern genre.

In the colony

In novels such as The Trial, the protagonist of which is arrested and ultimately executed by the police but who never finds out his crime, Kafka shows how bureaucracies can become sadistic operations dedicated to nothing more than perpetuating themselves.

Kafka’s own politics were informed by the bohemian and socialist circles of his native city of Prague, and his depiction of inhuman power reflected the increased power of European states, which used both systematic violence and draconian laws to control populations at home and in the colonised world they had won by force.

His 1914 short story In the Penal Colony is set in an unnamed colonial penitentiary, where prisoners are executed by a machine that slowly tattoos their sentence onto their skin as they die in prolonged agony.

Even more shocking than the actual torture device, which a former commander handed down, is how the characters who oversee this infernal machine feel incapable of stopping its use. Despite its obvious cruelty, they maintain it. Kafka writes, “The colony forms such a self-contained whole that his successor, even if his head was bursting with new schemes, would find it impossible to alter any part of the new system, at least for many years to come.”

Related article:

The term “Kafkaesque” invokes the nightmarish quality of his fictional worlds – which often involves irrational and sadistic centres of power – and what he shows through In the Penal Colony is that human action enables these horrors. The soldiers and functionaries who run the machine could stop it at any time, but choose not to.

Kafka died in 1924, but his work anticipated the horror of fascism, a political ideology that actively revelled in sadism. The Nazis who presided over the Holocaust, where millions of people – including three of Kafka’s sisters – were murdered at an industrial scale, were not supernatural monsters, but ordinary men and women who became cogs in a machine of mass bloodletting.

The institutional perversity of In the Penal Colony still exists in the bleak prisons and border detention centres around the world. In the 21st century, governments respond to the social problems of poverty and migration by warehousing refugees and non-violent offenders in carceral systems that serve only to inflict pointless suffering.

Corporate horror

While Kafka addressed the horrors of which nation-states are capable, contemporary creators are detailing the nightmares of neoliberalism and entrenched corporate power.

As economist Peter Fleming writes, “With current trends unfolding as they are, a new dark age appears imminent, in which corporate fiefdoms and global plutocrats preside over an increasingly disenfranchised transnational population and dying natural environment.”

Neoliberalism has also unleashed an epidemic of psychic stress and pain, seen in the proliferation of mental health disorders. Advertisers and the media tell us that consumer capitalism is the peak of human happiness, while we feel more wretched and hopeless than ever.

This bleak absurdity is portrayed in the TV show Corporate (2018-2020). While ostensibly a comedy, the show’s depiction of office life at the corporation Hampton DeVille is a Kafkaesque horror-sitcom. Hampton DeVille is a proudly evil corporation, invested in building products like an apocalyptic “weather machine”. Not only will it happily destroy the planet for profit, it also turns its own staff into miserable and pessimistic office drones.

According to co-creators and stars Matt Ingebretson and Jake Weisman, the bleakness reflects the contemporary fear “that corporations infect every single part of our lives. They’ve won. They’re the new nations … [Hampton DeVille] is a company that’s insatiable and sort of represents the drive and unending greed that comes out of working in capitalist society. If it were the number one company in the world, it wouldn’t be enough. They have to be bigger than number one.”

Towards obsolescence

The insatiable drive of contemporary neoliberalism is a key theme in the “corporate horror” of author Thomas Ligotti. For many years a cult literary figure among horror fans, he gained wider public attention after his writing inspired Matthew McConaughey’s pessimistic monologues in the first season of True Detective (2014). His short stories collections Songs of a Dead Dreamer (1985) and Grimscribe: His Lives and Works (1991) were reissued under the prestigious Penguin Modern Classics imprint.

In short stories such as Our Temporary Supervisor, in which a monstrous being is hired to improve work performance in an anonymous office space, Ligotti holds a distorting mirror to the orthodoxies of neoliberalism. He suggests that capitalism has become autonomous from human control or needs, dedicated only to the endless promulgation of useless commodities.

This image of terminal-stage capitalism is chillingly described in the novella My Work is Not Yet Done, in which the nameless narrator describes how “the company that employed me strived only to serve up the cheapest fare that its customers would tolerate, churn it out as fast as possible, and charge as much as they could get away with. If it were possible to do so, the company would sell what all businesses of its kind dream about selling, creating that which all our efforts were tacitly supposed to achieve: the ultimate product – nothing. And for this product they would command the ultimate price – everything.

Related article:

“This market strategy would then go on until one day, among the world-wide ruins of derelict factories and warehouses and office buildings, there stood only a single, shining, windowless structure with no entrance and no exit. Inside would be – will be – only a dense network of computers calculating profits.”

This stark image is reminiscent of the gleaming new Amazon warehouse built next to a shack settlement in Tijuana, Mexico. Corporate monoliths are looking forward to a future of automated workspaces where humans are obsolete, while the world outside becomes even more depleted and impoverished.

The global success of the South Korean show Squid Game, in which people drowning in debt participate in deadly games to win money. Behind the scenes, the games are created for the enjoyment of perverse powerful men. The series shows how corporate horror tropes resonate with audiences. Although it reflects the specific inequalities and contradictions of Korean society, its vision of relentless and murderous exploitation resonates with international audiences because its speaks to a generalised condition of increasingly feral and destructive capitalism.

The absurdist vision of horror serves an important subversive function. It encourages a scepticism about state and corporate power, reminding us that the dreams of the powerful are often nightmares for the rest of us.