Sport’s scramble for Africa

With the English Premier League leading the pack, European and American sporting bodies are on a fierce drive to expand their dominance in Africa. What does it mean for the continent?

Author:

17 August 2021

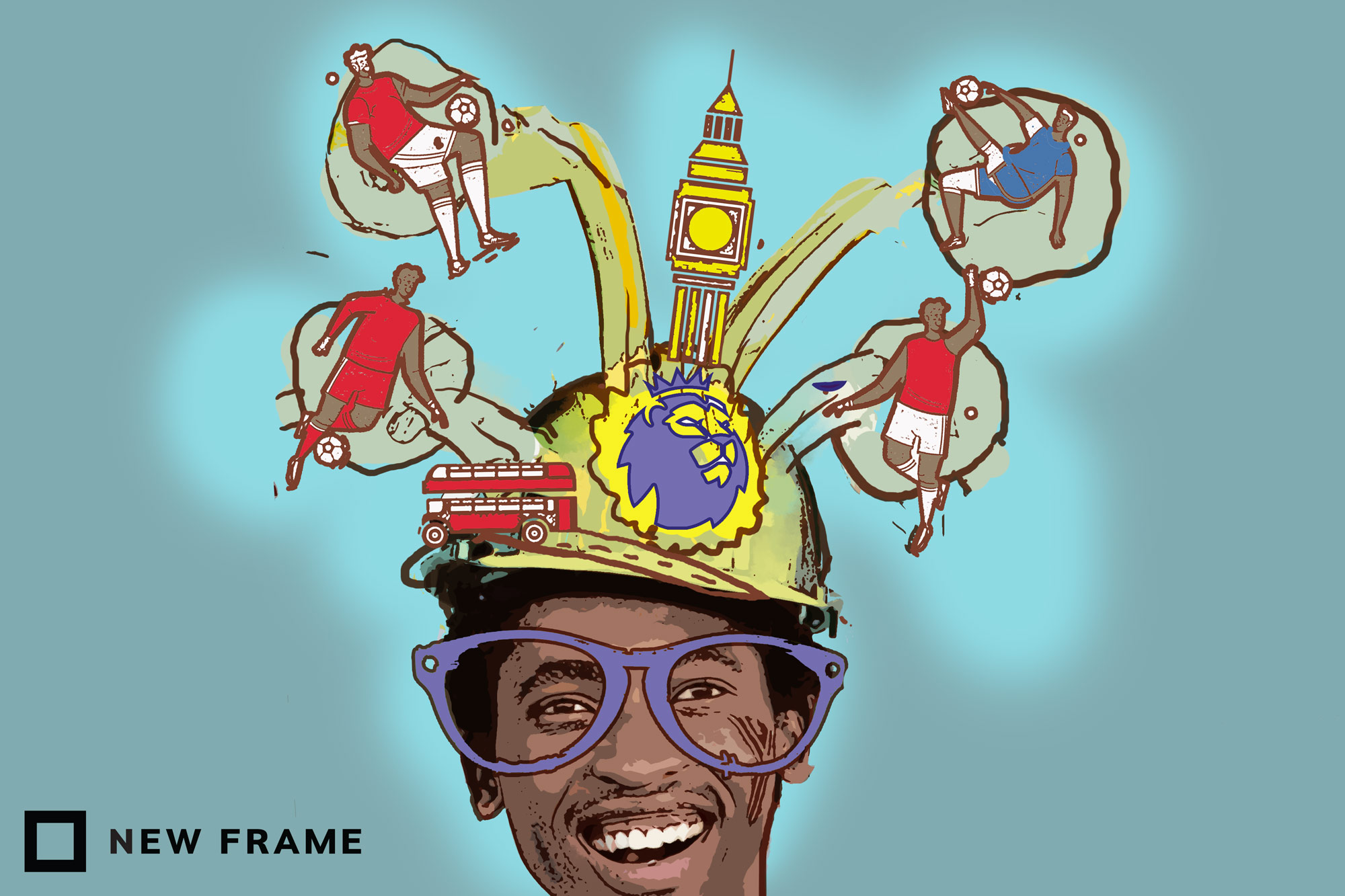

The English Premier League is a global behemoth. It has become Britain’s most recognisable global brand, trumping the likes of the royal family, Rolls-Royce and the BBC, and dominates football in Europe, the Americas, Middle East and swathes of Asia and Africa.

Janan Ganesh, the esteemed Financial Times columnist, wrote in 2019 that “the Premier League is not just another of the country’s ‘soft power assets’. It is the main one.” He noted that from Wyoming to Wellington, the appeal of the Premier League is almost universal and allows Britain to present a face to the world that is different to the “Olde England” of “Harry Potter and Downton Abbey”.

While the league’s commercial relevance is well known, and has been magnified in the wake of the European Super League debacle, there is an often overlooked dimension that merits consideration: sports diplomacy. As observed by Kenyan Milimu Ellen Busolo in her 2016 master’s degree thesis on this subject, “When sport goes beyond national boundaries, it becomes an intimate companion of diplomacy.”

Related article:

Simply put, sport diplomacy is when a country advances its strategic interests and policy goals through sport. It is an example of using soft power as a means to success in world politics. Such endeavours, according to Harvard governance professor Joseph Nye, enable a country to “engage with the world, communicate a set of values it seeks to uphold, project an image it wants others to have of it and gain access to resources and markets around the world”. Nye identifies three pillars of soft power: political values, culture and foreign policy.

To this end, the global appeal of the Premier League represents a unique opportunity for Britain, which is seeking to expand its global influence post Brexit. Done right, it offers a chance to forge new relationships with countries across the globe. The catch here is that, unlike during colonialism when the one-sided nature of the “relationship” was obvious, football gives a false sense that the relationship is mutually beneficial, especially when considering the stars from the Global South making millions in England. But in some countries, the Premier League’s success comes at a detriment to their domestic leagues.

The value proposition

Africa, with over 1.2 billion people, many of whom are football obsessed, is an appealing market for the Premier League. With the continent likely to be an emerging engine of global growth, the commercial and strategic rationale for both investment and attention is obvious.

There are both practical and strategic reasons for the Premier League representing a clear and compelling value proposition for Britain. For one, it is popular. Manchester United, Liverpool, Chelsea and Arsenal are instantly recognisable brands the world over, including in Africa. And a steady rise in the number of African players successfully plying their trade in the league has magnified its appeal on the continent.

Since 1992, when Peter Ndlovu of Zimbabwe became the first African to play in the Premier League, the influence of African players has steadily risen. The likes of Lucas Radebe, Didier Drogba, Jay-Jay Okocha and Nwankwo Kanu have become cult heroes at their respective clubs and their success has paved the way for African footballers to shine. There are now about 50 Africans playing in the league, and they are excelling.

The top scorers in the 2018-2019 season all hailed from the continent, with Sadio Mané (Senegal) and Mo Salah (Egypt) from Liverpool sharing the Golden Boot alongside Arsenal’s Pierre-Emrick Aubameyang (Gabon). Their success resonates with the average African citizen, showing that Africans have the talent and ability to compete with the very best in the world. This aspirational appeal cannot be overstated.

Related article:

Next is penetration. The Premier League is watched by 4.7 billion people worldwide. Television coverage of the league in Africa surpasses that of even channels in Britain. SuperSport, a subsidiary of the MultiChoice Group, Africa’s largest media and entertainment company, recently extended its Premier League broadcast partnership in sub-Saharan Africa until the end of the 2024-2025 season in a deal that includes rights to air all of the league’s 380 matches per season.

With social media and online streaming services rapidly expanding, the Premier League’s digital footprint and brand recognition across African markets are soaring. New modes and mediums of communication, including the explosion of smartphones on the continent, will further fuel the demand for such content. Although exact numbers are hard to ascertain, it is estimated that viewership of the league on any given weekend in Africa is around 300 million – and growing.

Third is proximity. Two factors in particular stand out: colonial legacy (Britain’s cultural proximity and linguistic, legal and educational symmetry, and sizable diaspora) and the timing of most games (early afternoon or evening when most people are socialising).

A powerful export

Alistair MacDonald, a policy adviser on soft power at the British Council, observes that “Premier League football plays an essential role in shaping perceptions of the UK, in attracting people to come to visit, study, live and do business in Manchester, Leicester, Cardiff, and other towns and cities up and down the country”.

With the right level of strategic thinking and tactical nous, Britain could leverage the Premier League to export the values and vision espoused by “Global Britain”. It is by far the nation’s most successful sporting export, watched live each week in more than 200 countries, and earnings from international television rights alone exceed £4.7 billion.

In this regard, there are obvious parallels with the Chicago Bulls and Michael Jordan, Nike Air and the globalisation of the National Basketball Association (NBA) in the 1990s, all of which were hugely successful in promoting American pop culture globally. They all became symbols for the ideas and values that embodied the Washington Consensus – the dominant economic and political ideology of the post-Cold War era.

Related article:

Together, they were hugely effective in signalling the virtues of American-style capitalism, democracy and liberalism to global audiences. By allowing people in faraway lands to identify with the lifestyle, vision and values of its “exports”, the United States was able to create a strong affinity for its “brand” and enhance its global reach and relevance using soft power.

Such messaging has assumed even greater importance in the current context. In an emerging game of geopolitical chess in which Africa is being courted by global powers for its resources and economic opportunities, Global Britain could leverage the attraction of the Premier League into something tangible and beneficial.

The Premier League – by virtue of being the most lucrative, competitive and prestigious league in the world – carries a unique attraction. It functions as a true meritocracy, it is truly cosmopolitan and is the gold standard for technological innovation and modernity. In short, it features the best and brightest from across the world and is the benchmark for excellence. It is the perfect advertisement for post-Brexit Britain, which is aiming to market itself as a multicultural, diverse and prosperous society.

Not a one-way street

Far from being a new imperialist lever, the benefits of a relationship with the Premier League have the potential to work both ways, especially for governments who also want to sanitise their image through the power of sport. In 2018, Rwanda became the first African country to partner with a Premier League club to attract tourists, and its Visit Rwanda initiative with Arsenal was credited with boosting tourism by 8% in its first year.

“Before the partnership was signed, 71% of the millions of Arsenal fans worldwide did not consider Rwanda a tourist destination. At the end of the first year of the partnership, half of them considered Rwanda a destination to visit,” said Belise Kariza in 2019, when she was the chief tourism officer of the Rwanda Development Board. Soon thereafter, Liverpool announced a three-year partnership with the Mauritius Tourism Promotion Authority and Economic Development Board.

The purpose of such initiatives is two-fold. First it is to generate increased revenues, investment and tourist volumes. Second, as in the case of Rwanda, it is to change a country’s image in the eyes of international audiences.

Related article:

The Guardian sports writer Barney Ronay remarked in March that “football has spent the past decade being bought and sold by sovereign states, used to puff, gloss and scour international reputations”. This “sportswashing” tactic – the manipulation of sport to whitewash their reputations abroad, as well as to further political agendas – is not unique to Rwanda. Other countries with questionable human rights records such as Qatar, China and Russia have attempted to improve their image among global audiences by using the power of football to their advantage.

The unsavoury nexus between power, money and politics and their encroachment on the sport has received strong backlash from fans and human rights groups alike. Using football as a vehicle to overlook moral failures in exchange for monetary compensation is an anathema to the values of the sport.

Yet this forms part of a broader strategy by Rwanda to change its global reputation and deflect attention from its democratic deficit and questionable human rights record. The Arsenal deal, the 2019 tie-up with Paris St Germain and the NBA’s inaugural Basketball Africa League (BAL) that was held in Kigali all form part of a deliberate “sportswashing” campaign.

Credible competition

Despite its considerable advantages, the Premier League isn’t guaranteed this dominance for years to come as there is fierce competition looming. Other countries and other sporting codes are jostling for a slice of Africa’s audience.

Intriguingly, La Liga of Spain – a country with little historic affiliation or presence in Africa – opened its first office on the continent in 2015, in Johannesburg. Since then, its expansion has been rapid, laying the foundations to build a Spanish football legacy across the entire continent. “La Liga has evolved from being an unknown brand for South Africans to being the second-most important foreign league in the country,” said Marcos Pelegrin, its southern Africa managing director.

For La Liga, Africa is the fastest-growing region in terms of audiences, with media exposure doubling during the 2019-2020 season. With strong growth, new commercial partnerships and expanding digitalisation, new internationalisation opportunities are being created for Spanish clubs. Real Betis, for example, recently launched an academy in Zimbabwe.

The BAL, whose enterprise value is estimated at nearly $1 billion, is another example of how sport is being used to advance America’s economic and cultural influence. The founders and investors of the league have identified four primary avenues for commercial success: Africa’s talent pipeline, the expansion of television and media rights, sponsorships, and the growth of sales merchandise, all of which can be used to expand its fan base.

Related article:

To this end, the NBA has invested heavily in initial infrastructure with a view of turning the league into a scalable, commercial product. With increased popularity and participation, the NBA envisions basketball being a top sport throughout Africa within the next 10 years.

Sports in Africa is big business, evidenced by the increasing involvement of private equity players, governments and big brands in this space. Roc Nation, a global talent management agency owned by rapper and businessperson Jay-Z, has steadily been expanding its footprint in Africa, bringing a number of high-profile sportspeople and clubs into its stable.

All these companies and enterprises recognise not only the commercial viability of their endeavours, but also their ability to build influence. The continent has a consumer market that is simply too big to ignore. And they, and governments, recognise the potential for sport in Africa to turn into the next big lure for foreign direct investment.

Open to exploitation

In a world where geopolitical realignment is taking place, post-Brexit Britain is looking to forge new and strong strategic alliances and relationships to boost its economy. Using foreign policy as an economic stimulus is vital in achieving this, and Africa is appealing in this regard. For British businesses, Africa’s high economic and population growth rates, urbanising population and growing consumer market provide a marketplace for British goods and services.

While this is good for African football talent, it poses a serious threat to domestic football if not managed correctly. A number of leagues on the continent are already rendered insignificant because the English Premier League is regarded as king. It also puts a spotlight on the issue of talent migration and the constant flow of top talent out of African leagues and into the Premier League – the sporting equivalent of the “brain drain”.

Related article:

This one-way stream of player movement has been beneficial to national teams in Africa as it allows their players to train regularly with the best in the world, but it prevents the nations from gaining any sort of financial benefit for the talents of their players. Advocates of the Premier League will argue that this is simply a function of the globalisation of football, but a more sinister explanation for the player movement from Africa to Europe is neo-colonialism or exploitation of African labour.

Telford Vice argued in New Frame in 2019 that the political economy of football is “bound up with Britain’s historical tendency, and England’s in particular, to take what they want from other countries and those countries’ people, use them up and, once that’s done, discard them and deride them as uncivilised and backward”. For critics, it cements that idea that sport, and in particular football, is being used as a neo-colonial lever, albeit a more subtle one, to assert dominance and entrench historical power dynamics.

For Africa, it will be important to guard against football being used as a tool for cultural imperialism in this new era of geopolitical competition, especially when considering its history of exploitation. Having fallen victim to “divide and conquer” strategies during both the colonial period and the Cold War, the continent will require a more streetwise and savvy approach to avoid losing out on its fair share of the spoils.