Sport’s fairness vs inclusivity debate rages on

New Zealand weightlifter Laurel Hubbard put the spotlight firmly on the issue when she became the first openly transgender athlete to compete in the Olympics.

Author:

11 September 2021

What is the purpose of elite sport? After all, organised games of any sort can be rendered meaningless if you pull at the thread for long enough. But to paraphrase the renowned Uruguayan football writer Eduardo Galeano, the games we play have always told us who we are. And more than most other multinational events, the great quadrennial (or so) jamborees that are the Summer Olympics and Paralympics serve as a temperature check for global politics and the contemporary social order.

Anyone paying attention did not need to read the recent report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change to know that the outlook is bleak. In July, as many as 500 Canadians died from heatstroke in the province of British Columbia as the thermometer reached 49.6°C. In August, the Italian island of Sicily recorded a European high of 48.8°C. Catastrophic events around the world are now met with the same shrugs that once greeted another Michael Phelps gold medal in the pool.

Related article:

It is astounding, then, that the climate crisis wasn’t mentioned once during the men’s marathon won by Kenya’s Eliud Kipchoge. The Olympic event took place in Sapporo, about 1 100km north of Tokyo, to mitigate high humidity levels and stifling heat in Japan’s capital. It also started an hour earlier than originally scheduled to avoid the sun at its zenith. These details were spoken of as a matter of fact rather than the consequences of a planet hurtling towards an uninhabitable dystopia.

A valid counterargument is built around the notion that sport’s primary function is to entertain and that talk of melting ice caps and rising sea levels detracts from the feel-good energy. But to blatantly ignore the growing elephant of doom requires a degree of mental gymnastics that would rival a Simone Biles somersault. No sport exists in a vacuum. Every event must be placed within a broader context.

Can’t deny reality

This is why, when sprinter Krystina Timanovskaya criticised her national team coaches, it was worth knowing that she is from Belarus, a country ruled by the iron fist of Alexander Lukashenko. The chain of events that culminated in her and her husband seeking asylum in Poland only makes twisted sense when the broader sociopolitical narratives are explored and understood.

Why is there a need for a team that comprises only refugees? Why were Russian athletes not competing under their nation’s flag but on behalf of the Russian Olympic Committee? Why are female athletes so often scantily clad while their male counterparts are not? Is it any coincidence that the world’s economic superpowers comfortably finished around the top of the medals table?

The answers to these questions require investigations of their own. For now, let us focus on what was arguably the most contentious conundrum over the several weeks of the Olympics and Paralympics in Japan: Is fairness or inclusion more important in elite sport?

“For me, the most important thing in sport is that it accurately reflects the society in which it exists,” says Hlengiwe Buthelezi, an LGBTQIA+ rights activist based in KwaZulu-Natal and a co-organiser of the Afro Games, a localised offshoot of the global Gay Games that has provided a platform for LGBT athletes since 1982.

“Yes, winning is important, and yes, we want to see our heroes bring back gold medals for our country. But what values are we willing to sacrifice for gold medals? What messages are we giving to our young people if we say that one person has a right to compete and others do not? Sport holds a mirror up to the world. It’s our job to make sure that we recognise the reflection.”

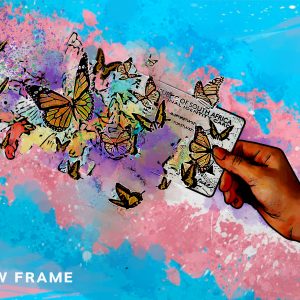

The conversation with Buthelezi begins and ends with Laurel Hubbard, 43, the New Zealand weightlifter who became the first openly transgender woman to compete in an Olympic Games. Though she failed to register a clean lift in three attempts in the women’s +87kg category, Hubbard’s inclusion will nonetheless be remembered as a watershed moment.

Mixed feelings

“I was torn watching Hubbard,” Buthelezi says, “because obviously it was a momentous day for trans athletes. Seeing her on the biggest stage was amazing and will inspire others. But then I thought of Caster Semenya and remembered that she was not allowed to defend her Olympic title. This didn’t make sense and brought me back to this question we’re discussing. What is fair in sport? What is right? How can one thing be true for one person but not true for another?”

The reason Buthelezi mentions Hubbard and double Olympic 800m champion Semenya in the same breath is because both athletes were born with higher testosterone levels than almost all the women they compete against. This hormone, which is responsible for increases in bone mass, muscle density, blood flow and lung capacity, and fat regulation, is far more prevalent in people who went through puberty as a biological male than those who did as a biological female.

Related article:

According to renowned sports scientist Ross Tucker, testosterone is the most significant variable in human performance. “It is known that biological males, whose puberty and development is influenced by testosterone, are stronger by 25% to 50%, are 30% more powerful, 40% heavier and about 15% faster than biological females,” Tucker says.

In the seven months leading up to Tokyo, as many as 743 men recorded faster times than the women’s 100m world record of 10.49 seconds set by Florence Griffith Joyner in 1988. In that same period, 971 men beat the women’s 200m world record, 462 men beat the women’s high jump world record and 198 men beat the women’s 100m freestyle swimming world record.

A similar pattern emerges in every other sport that uses centimetres, grams or seconds to distinguish its champions. “This is why we have separate categories for men and women,” Tucker says. “If we didn’t, women would all but disappear from the elite level. With the exception of a handful of events like gymnastics, equestrian and archery, no woman would qualify for the Olympics ever again.”

Contentious rules

As such, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) had established guidelines that set a limit of one’s testosterone level below 10 nanomoles per litre of blood. This must be maintained for 12 months prior to competition.

Hubbard, who transitioned in 2012, had adhered to the requirements before competing in Tokyo. Semenya, who was born with what is called a difference of sex development (DSD), has naturally occurring high testosterone levels and has refused to undergo hormone therapy. “No freaking way,” she declared to the SABC in 2019. But her defiance, which has taken her all the way to the European Court of Human Rights, has resulted in her exclusion from her sport.

“I am convinced that if Semenya were white, she would be competing,” Buthelezi says. This sentiment gained further traction after Namibian sprinters Christine Mboma and Beatrice Masilingi were barred from the 400m event, and Francine Niyonsaba from Burundi was similarly prohibited from taking part in the 800m. All three athletes have high testosterone levels as a consequence of their DSD.

The controversial rule banning DSD athletes from competing at distances from 400m to 1 500m is under review. The IOC medical and scientific director, Richard Budgett, stated that the current policy needed amending as it is not “ethically or legally fair”. The new framework, Budgett said, would not focus solely on testosterone levels and would also consider the safety of athletes.

This news arrived too late for Semenya to defend her Olympic crown, and sports governing body World Athletics is facing calls to scrap the regulations after its scientists admitted some of their findings were “on a lower level of evidence”. Furthermore, the British Journal of Sports Medicine, which published the original evidence that led to the rule, has now released a “correction” to that 2017 paper, causing campaigners to advocate for scrapping it immediately. Semenya’s lawyers have rightly wondered why these findings were released after the Olympics had concluded.

Flawed science?

No matter, these developments have been welcomed by Kirsti Miller, an Australian athlete and activist who transitioned from male to female in 1999 and has become an outspoken critic of the science that has shunted DSD and trans people to the periphery of elite sport.

“Trans women are not a monolith and to make a blanket decision or judgement on trans athletes is wrong,” Miller says. “Secondly, there are significant drops in performance after hormone replacement therapy. Endurance levels already decrease after six months. Haemoglobin levels decrease after three months. VO2 levels [the rate of oxygen consumption during exercise] is reduced after six months.”

Related article:

Miller also claims that conditions such as osteoporosis, muscular atrophy and various lung disorders can be attributed to hormone replacement therapy. Indeed, Hubbard sustained a potentially career ending elbow injury in 2018, which Miller says was “without doubt a direct result of her body suffering complete androgen deprivation”.

Tucker counters this, stating there is no scientific evidence to suggest that hormone replacement therapy is the cause of these conditions. “If someone was going to develop osteoporosis as a trans woman they would have probably developed it as a biological male,” he says.

The debate around fairness and inclusivity quickly devolves into a he-said-she-said verbal tennis match. There is no end in sight because the two opposing camps are arguing different points. “Inclusion cannot coexist with fairness,” Tucker argues.

Buthelezi counters: “Sport is for everyone. Sport without proper inclusion is by definition unfair.”

Hard job gets harder

In the middle of this political and social tug of war are the athletes. Speaking after her appearance in Tokyo, Hubbard offered some insight into what it was like being one of the most scrutinised athletes in Olympic history.

“I’ve tried not to dwell on negative coverage and negative perceptions,” she said, “because it makes a hard job even harder. It’s hard enough lifting a barbell, but if you’re putting more weight on it then it makes it an impossible task.

“Often, a lot of negative coverage and negative perception is not really based on evidence or principle, but is based on emotion … people are often reacting out of fear, discomfort. I hope that in time they will open themselves up to a broader perspective. All I’ve ever wanted to be is myself.”

Tokyo saw five sports, including skateboarding and surfing, make their Olympic debuts. At Paris 2024, breakdancing will join the list. This is in response to shifting demographics and the Games’ need to appeal to a younger audience. Change is not only necessary, but inevitable.

The new Olympic motto is a simple one: “Faster, Higher, Stronger – Together”. The first three words state the ambitions of those select few whose virtues and gifts inspire and enthral billions around the world.

But they mean nothing without that final word in the equation. The games we play do not exist in a vacuum, and neither do the athletes who play them better than most of us could hope. And if the athletes don’t represent us, and their triumphs and failures aren’t representative of the world we all inhabit, then it is worth asking what the point really is.