Soweto’s centre for human development through music

Many young people in Jabavu and White City are on a long waiting list for a place at a music institution that teaches more than music and is a portal to potential success.

Author:

27 January 2022

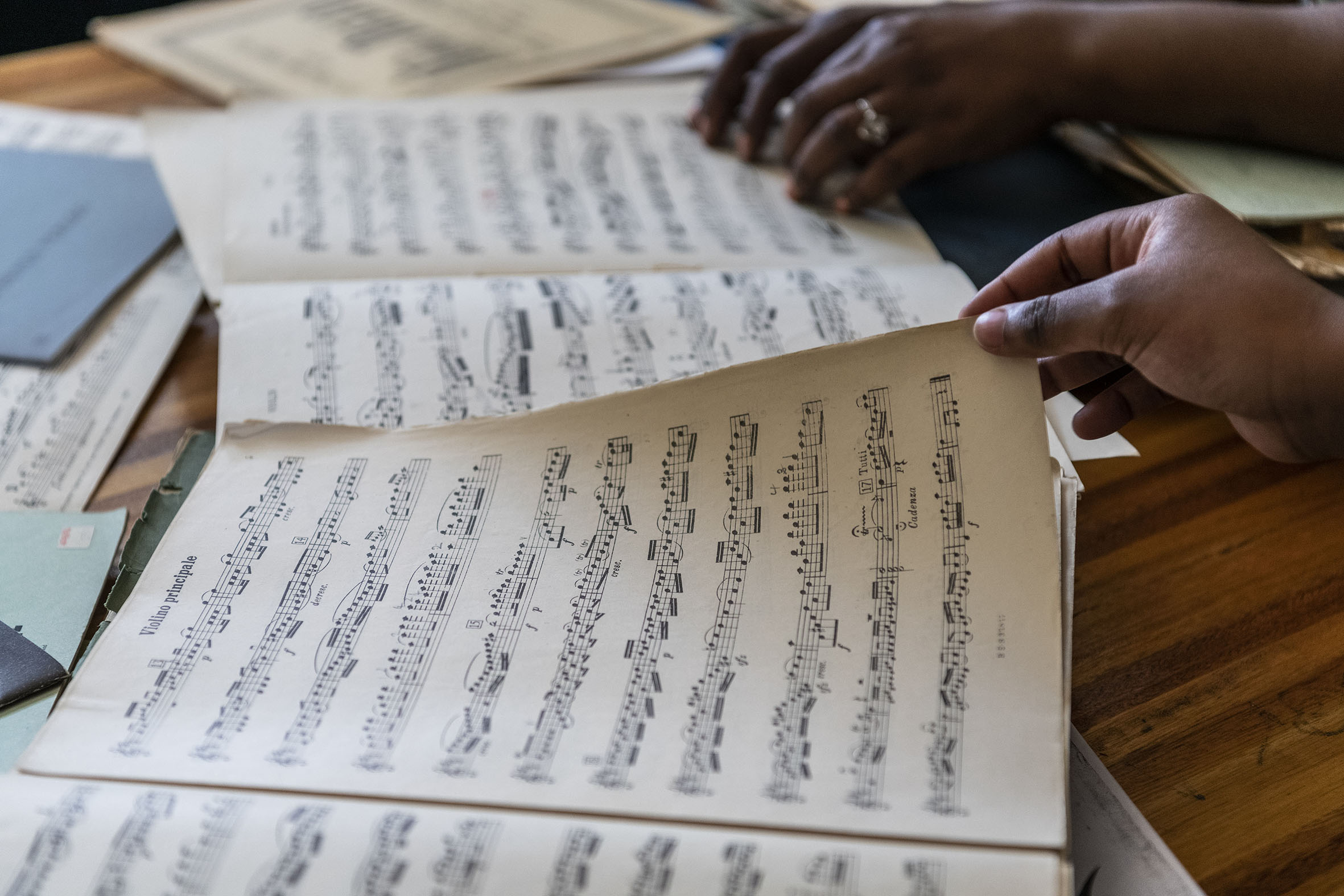

On any given afternoon, a select and excited group of young people, between the ages of eight and 18, can be found in one of the rehearsal rooms at the Morris Isaacson Centre for Music (MICM). It is there that they hone their craft under the eyes of dedicated teachers.

Some of these teachers have performed on grand stages around the world. They are now giving their time to nurturing the next generation of musicians.

For Phumla Makapela, having her daughter in the centre means a chance at otherwise unattainable opportunities. Makapela’s nine-year-old, Ataahua, specialises in the cello.

“MICM takes kids away from the streets, from just hanging around, [and] provides that awakening feeling … in terms of understanding that this small instrument, a violin that can fit in your hand, can open a whole lot of doors,” says Makapela.

Like many parents who have secured places for their children at MICM, having been on the waiting list for a long time, Makapela believes that the centre allows children and young people a chance to broaden their horizons and imagine alternative realities outside their accustomed township existence.

Litha Booi, 12, who has been at MICM since 2016, says: “We also come on Saturdays, when most of us are free. So, coming here keeps us busy [so we are not] drawn to things like drugs.” Booi currently specialises in djembe and drum kits.

“The centre takes our kids to the world. It takes them out of Soweto to Cape Town, to KZN [KwaZulu-Natal] … and provides intercultural learning in a musical form,” Makapela adds. She is also involved in the recently launched MICM Book Club that aims to nurture a love for reading while also helping learners develop their reading and comprehension skills.

Music and beyond

Lungile Zaphi, the director of MICM since 2020, joined the centre as an administrator in late 2018. For her, it is an important space within the community – not only because it shares a name with the historic Morris Isaacson High School, but also because of its positive contribution to the community beyond music.

An initiative that shows this is the partnership with The South African College of Applied Psychology. The organisation offers counselling, homework help and emotional support to the learners at MICM. Most recently, a community-led gardening project was set up at the centre.

As a non-profit organisation (NPO), MICM has not been spared by the Covid-19 pandemic, and Zaphi has had to make some tough decisions to ensure the centre’s survival. “We had to take some drastic decisions by cutting down our costs – which means cutting down people’s salaries – because we wanted to preserve the little that we have,” she says.

A key part of those survival strategies has included what she describes as being “creative about what we do and how we can use music as a tool for change”. This has seen the strategic alignment of MICM programmes with those of corporates and other organisations at a time when many are cutting down corporate social investment support and redirecting finances towards Covid-19 mitigation efforts.

Chris Bishop, the MICM director of music, says that practical ability and theoretical-literacy understanding is prioritised and both are equally important.

MICM has 116 students and offers instruction on a range of instruments, which include violin, pennywhistle, djembe, drum, trombone and double bass.

The centre also works with Ugubhu Nezinsimbi Zomculo Wesintu, an NPO housed on the same premises, which specialises in making and teaching indigenous instruments. In addition to giving instruction on the playing of such instruments as uhadi, makhweyana and mqangi (bow instruments) – as well as pennywhistle, marimba and djembe – the Ugubhu team also teaches painting, puppet-making and bead-making as part of their community outreach activities.

Leon Moloi, who works as an external programmes coordinator at MICM, says their role is summed up in the phrase: “Youth-skills development programme through arts.”

The school’s glowing reputation has seen at least 10% of their students being admitted to the National School of the Arts every year. They have also established relationships with institutions like the Stellenbosch University Conservatory and the Royal Birmingham Conservatoire in England. The United Kingdom institution has, since 2015, been giving Skype lessons to 24 MICM learners.

‘Catching them young’

MICM also has a dedicated early childhood development (ECD) programme, which has seen them send their teachers to places like Rebone Botshelo Children’s Centre daycare and preschool to teach children basic music skills. With this “catching them young” mantra in place, MICM ensures that ECD centres in and around Jabavu and White City in Soweto benefit from their expertise.

Theresa Mbatha, who runs the ECD and the beginner’s basic music theory class says: “Music is the only subject where all four parts of the brain function at the same time. While you are reading, you are playing, and you are singing and thinking of the interpretation.”

For 16-year-old Mbali Patho who started playing violin when she was eight, it was the sounds of a popular musician that sent her running to MICM, with a burning desire to learn to play a musical instrument.

“When I first came to this centre, it was when Zahara was very popular and I decided I wanted to play [the] guitar. I was hoping to be the next Zahara, but I found out that [the] guitar class was already full,” says Mbali. She then took up the violin – and it has enabled her to perform at festivals as well as travel to the United Kingdom.

Cello teacher Daliwonga Tshangela has been with MICM from the beginning. Robert Brooks – who co-founded the centre with late philanthropist and Cape Gate chairman Mendel Kaplan – invited the musician to come to teach. Tshangela had trained in Diepkloof under Kolwane Mantu, founder of the African Youth Ensemble.

In an area like this, “this becomes the only other world into something that is non-academic, but it allows them to access their inner brilliance and their self expression, which is critical to the development of children and young people”, Tshangela says.

As centre director, Zaphi thinks that “it is important for the government to understand the importance [of the arts]” so they can adequately support initiatives such as MICM.

There is something special happening at MICM. Having spent some time there, you can see that they are bringing to life their motto of “human development through music” and truly affecting the lives of young people as well as the wider community they serve.