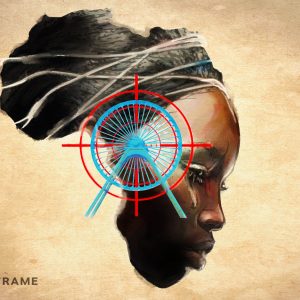

South Africa’s mental health facilities are ailing

The Human Rights Commission has found a lack of staff, beds and clean, secure facilities plague institutions across the country, leaving patients unable to access the help they need.

Author:

7 April 2021

Just over three years ago, on 18 March 2018, Justice Dikgang Moseneke ordered the government to financially compensate the victims and families of the Life Esidimeni tragedy in which 144 people died at psychiatric facilities. The judge also ordered that the dead be memorialised.

To date R6.5 million of the R120 million budgeted has been paid out. While families involved directly in the arbitration have received compensation, others are still waiting. “The difficulty according to the premier’s office is that they are verifying the applicants and won’t pay out until this happens,” said the Democratic Alliance’s spokesperson for health, Jack Bloom.

The families of the victims were resolute about wanting mental health services for the living rather than a monument to the dead. “We want a living facility, where we can be assured that people with mental illness are attended to. Our request was that in each region, there must be a major clinic where people who show signs of mental illness can be referred,” said Christine Nxumalo, whose sister died in the tragedy. If there is early detection, she said, people can be treated before they need to be institutionalised. “This was agreed, but nothing has happened,” Nxumalo said.

Neglecting mental health

In November 2017, the South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC) convened a national consultative hearing on the status of mental health care in South Africa. Although it was catalysed by the Esidimeni tragedy, the focus of the hearing was on capturing “a picture of the lived experiences of all people with psychosocial and intellectual disabilities in South Africa” and the impact of systemic, social, cultural, political and economic concerns that affect mental health and the realisation of human rights.

Many human rights violations were brought to light in the investigation. They arose, the commission said, from the “prolonged and systemic neglect of mental health at the level of policy implementation”. Under-resourcing and lack of professional expertise in the sector were the result of “system-wide failures to protect and promote the rights of this group”, the commission concluded.

An independent study in 2017 found that a mere 5% of the general healthcare budget was allocated to mental health. Before 2017 the amount allocated to mental health from the overall health budget was unknown and most probably quite a lot less, said Melvyn Freeman, a mental health consultant formerly with the Department of Health. “This is partly because expenditure in mental health is often integrated into general health budgets and therefore not calculated into estimates of mental health costs.”

Related article:

International best practice shows that governments should begin to invest in community mental healthcare services and general hospital psychiatry, while reducing support for existing stand-alone hospitals, said Lesley Robertson, a psychiatrist who served on the expert panel for the investigation into the deaths of Life Esidimeni patients.

The National Mental Health Policy Framework and Strategic Plan 2013–2020 was produced in 2012 with the aim of integrating mental health into general health services so people in need of treatment could access services at the community level. But the plan has not been implemented, apparently because no budget has been made available.

The South African Society of Psychiatrists informed the SAHRC that there was a severe shortage of psychiatrists in the country and the limited community-based care that was available for people with psychosocial and intellectual disabilities was very under-resourced. At a governance level, “dysfunctional or absent” mental health directorates and mental health review boards are prevalent, and there are very few services for children and adolescents.

The SAHRC prioritised implementing the mental health policy framework by national and provincial governments. The commission suggested a budgeting approach that takes into account the prevalence of mental illness with a particular focus on rural communities to ensure that budgets are not concentrated in urban areas and directed at psychiatric facilities only.

Facilities are in dire condition

South Africa has 22 dedicated institutions, most of which were built before 1910. There are significant variances in the availability, suitability and condition of facilities from province to province, although the overall picture gained at the SAHRC inquiry was very negative.

One of the SAHRC’s key recommendations was the establishment of a standing committee by the Department of Health. The standing committee recently held its first meeting, said Cassey Chambers, who represents the South African Depression and Anxiety Group (SADAG).

“They have been visiting mental health services – mainly hospitals and clinics – in all the provinces during lockdown and it is incredibly scary,” Chambers said. “Life Esidimeni highlighted all the issues in Gauteng, but here we have provincial data about what is available and what is happening: facilities not up to scratch or hospitals with no facilities and no professionals. It is very concerning. This will be the key document that will steer [the] SADAG’s advocacy for the year.”

Related article:

Andrew Petersen, whose uncle was a Life Esidimeni survivor, said: “Obviously government has the resources and they need to channel those resources towards mental health, but we are all responsible – civil society and all political parties – we are all responsible for advocating for improved mental health services and for more investment in mental health care. We all have to take responsibility as society.”

Specific recommendations were made for each province, including implementing the mental health policy plan, drafting budgets, establishing and staffing the necessary institutions, and improving services in prisons and psychiatric institutions that historically have been under-prioritised.

Understaffed and poorly run

The commission presented the results of its investigation in provinces to the Parliamentary Committee on Justice and Correctional Services on Esidimeni in December 2020. The findings included financial mismanagement and a lack of accountability; dilapidated, unhygienic and dangerous facilities because of a lack of maintenance by the Department of Public Works; no safety measures; a lack of mental health care wards; no facilities for adolescents; and chronic staff shortages.

Not a single institution the commission inspected had fire alarms and the majority did not have burglar bars on windows or secure fencing. In the new De Aar Hospital in the Northern Cape, the commission was shown an isolation room for housing psychiatric patients where the air conditioner was broken and the windows were not fitted with burglar bars.

In Limpopo, mental health patients were found in degrading conditions with no functional bathrooms and showers so dilapidated they did not have doors. Similar conditions were found in the psychiatric section of KwaZulu-Natal’s Madadeni Hospital, where patients were forced to shower and use bathrooms without privacy.

Most hospitals the commission visited did not have dedicated wards for mental health patients and in psychiatric hospitals across the country, there were not enough beds. The chief executive of the Kimberley Mental Health Hospital confirmed that the hospital has only one wing in operation because of shortages of staff and equipment, including beds. The commission was told that it took an excessive amount of time to transfer psychiatric patients from the 72-hour observation wards to the mental hospital because of insufficient beds.

Across the country there was a blatant lack of facilities for adolescents, although incidents of mental illness and suicides in the 15-to-25 age group increase every year. According to the South African Society of Psychiatrists, almost one in 10 teenage deaths is the result of suicide and up to 20% of high school learners have tried to take their lives.

Staff shortages were evident in all facilities, including new facilities visited by the commission. The upshot of this was overworked and tired staff, low morale and patients not receiving proper care.

Related article:

In Kimberley, certified state patients are kept in the prison because of lack of staff. This situation is not limited to one province. Mental health patients incarcerated in prisons received special attention from the SAHRC. The commission was informed that 4 304 mental health care users were in the correctional system in 2017. It was also found that the state of mental health services is especially poor in the criminal justice, forensic and correctional systems in South Africa.

In its report to parliament, the SAHRC said state departments “have been largely non-compliant with the commission’s recommendations and have failed to provide the commission with information on whether they intend to implement its recommendations”. The commission’s ability to fulfil its constitutional and legislative mandate is compromised by this lack of cooperation.

Without buy-in and collaboration from different sectors of the government, the human rights of people with mental illnesses will continue to be overlooked, and the necessary investment in mental health will not happen.

“In the end,” Freeman said, “it may not be how much of the health budget that gets spent that will make the big difference, but how much social development [on grants and other services], housing, transport, labour and others spend – and this cumulative amount – that will really matter. Mental health cannot just be a health problem and responsibility.”