South Africans push back on Shell’s Wild Coast plan

An oil and gas exploration survey off the Eastern Cape coast is scheduled to start in December. But fishers, residents, environmentalists and activists around the country want none of it.

Author:

25 November 2021

Residents and grassroots environmentalists will ramp up pressure against the government and fossil fuel giant Shell next week to call off the hunt for oil and gas in the Eastern Cape’s remote marine environment, off what is known as the Wild Coast.

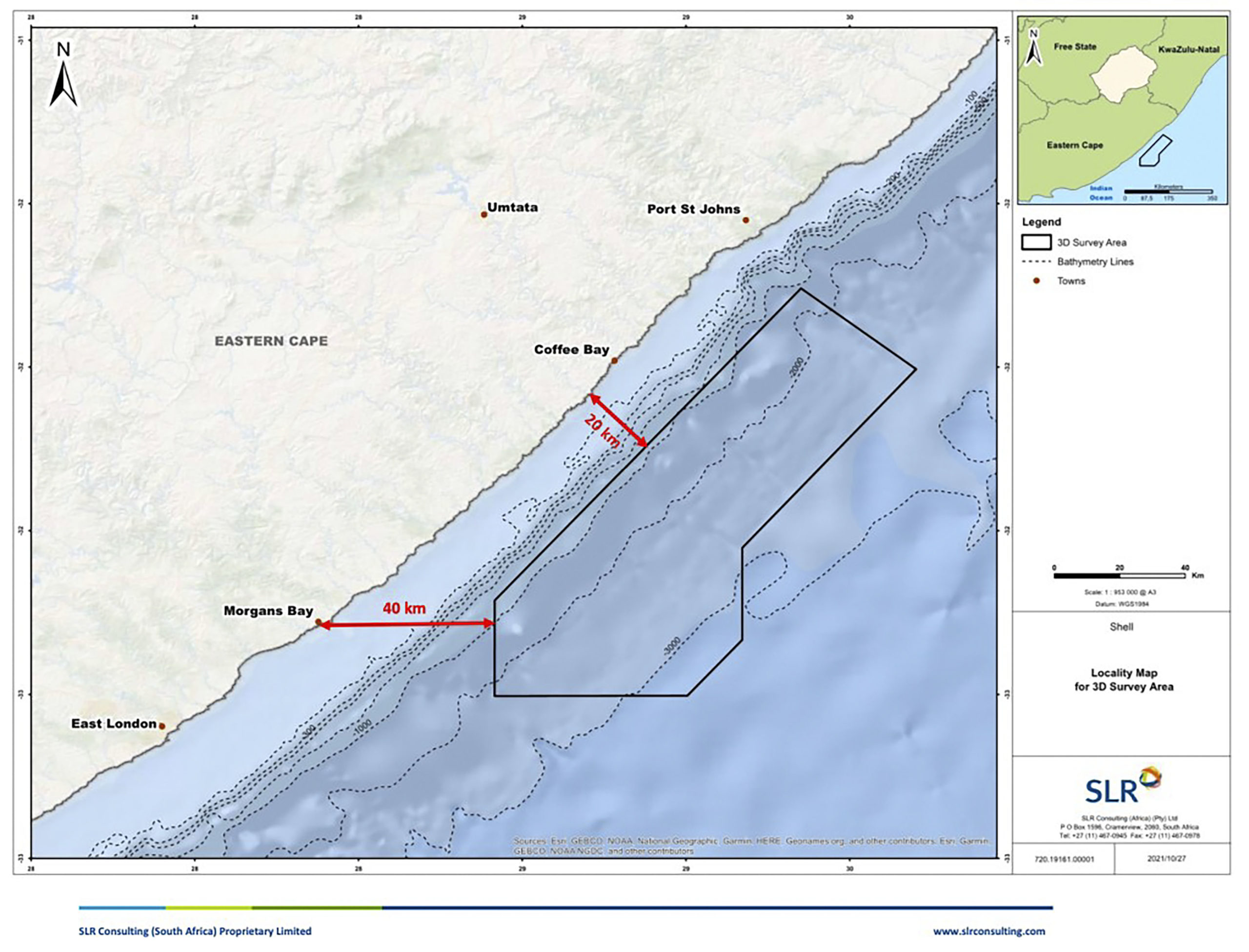

This follows news that Shell plans to embark on its major seismic survey off the coast between Morgan Bay in the south and Port St Johns in the north from 1 December. It involves blasting soundwaves into the sea with air guns every 10 seconds for the next four to five months, raising concerns about the impact of underwater noise on fish, whales and other marine life.

Though the survey will not involve drilling at this stage, the plan raises broader concerns around sea pollution, climate change, national energy policy and the future development of the region if Shell were to discover commercial quantities of oil or gas off this coast.

Related article:

But for now, the immediate concern is the impact of blasting waves of sound of up to 220 decibels into a marine environment abundant with fish and seafood resources, to map oil and gas pockets beneath the ocean floor.

More than 250 000 people had signed an online petition at the time of publication, demanding that the government pull the plug on Shell’s exploration plan.

Protests up and down the coast

At a local level, subsistence fishing communities are also raising their voices. They are planning protests and there are indications that some groups may seek a court interdict. A march along Wild Coast beaches on Sunday 5 December starts at the Mzamba River Estuary, according to Amadiba Crisis Committee co-founder Nonhle Mbuthuma.

The committee, which has also been resisting plans for a new toll road and dune mining operations along this coastline, were surprised that Shell would start a new oil and gas exploration project barely a month after the COP26 climate conference in Glasgow, Scotland.

“As a part of Operation Phakisa, Shell’s project has been allowed by our government, as if the threat of global heating from burning more and more fossil fuels doesn’t exist,” said Mbuthuma. Operation Phakisa is the government’s fast-track economic programme, which includes unlocking potential in South Africa’s oceans.

The Amadiba committee says blasting sonar canons poses a direct threat to marine life. “It is also a threat against the livelihood of communities along the Wild Coast and in KwaZulu-Natal, who use the riches of the sea to put food on the table and to get an income. This is our ‘ocean’s economy’. It is about food, not about mining the ocean to make profit for the minority rich who think you can eat money.”

Aside from the future risk of oil pollution if Shell finds viable volumes of hydrocarbons, the committee says that drilling the seabed could release other toxic substances into the marine environment.

“For over two decades, the coastal Amadiba community has fought against opencast mining on our land. Now we must also fight against mining of the ocean. Indigenous people along the whole coast of Africa must have the right to say no to projects that threaten their livelihoods, the right to free prior and informed consent.

“We call upon the South African government to acknowledge the climate crisis. More and more expansion of the fossil fuel economy is not the solution to the economic crisis. You cannot bring about economic recovery by threatening our livelihoods and the ecology of the ocean … Put the lives of people before profits. Withdraw the licence given to Shell for preparing mining in the ocean,” said Mbuthuma.

Members of the South Durban Community Environmental Alliance, including those from the KwaZulu-Natal Subsistence Fisherfolk Forum, are planning a “massive protest” in the Durban area on 9 or 10 December, according to alliance coordinator Desmond D’Sa.

“No one was told or consulted about this, and we cannot allow Shell to risk destroying our marine resources,” he said.

Strategic moves

The government originally granted an exploration permit to Impact Africa, a subsidiary of Impact Oil & Gas, in 2014. It later transferred some of its financial interests to ExxonMobil and a subsidiary of Norwegian group Statoil, now called Equinor. Shell entered the picture in November 2020, when it acquired a 50% interest in the exploration venture, with the remaining 50% held by Impact Africa.

Shell’s environmental consultants placed an advert in East London newspaper the Daily Dispatch in early November, advising that a seismic survey along the Wild Coast would begin around 1 December.

The standard Dear Sir/Madam letter that Shell’s consultants sent to a limited number of registered stakeholders says the survey covers an area of more than 6 000km² at depths of 700m to 3 000m. The exploration area is about 20km from the coastline at its closest point, according to the consultants.

That’s about the distance by car from Shell South Africa’s swanky headquarters in Sloane Street, Byranston, to the former head office of the ANC at Shell House in Plein Street, Braamfontein, in Johannesburg – cold comfort given that oil spills can spread rapidly over hundreds of kilometres.

Recalling the 1995 execution of Nigerian activist Ken Saro-Wiwa and the well-documented impact of oil pollution in the Niger Delta, D’Sa said Shell cannot be trusted to operate responsibly in Africa.

He drew attention to Shell’s recent announcement that it plans to relocate its headquarters and tax residence to London and drop the words Royal Dutch from its name, amid a corporate overhaul that has angered the Netherlands.

“This move to London makes it easier for them to not adhere to the demands for major carbon emission reductions,” said D’Sa, noting that a Dutch court recently ordered Royal Dutch Shell to reduce its carbon emissions by 45% by 2030 relative to 2019 levels. The landmark case, brought by environmental groups and more than 17 000 Dutch citizens, applies only in the Netherlands.

The Dutch pension fund for civil servants and teachers, APB, has announced that it will no longer invest in producers of oil, gas and coal. APB will also dispense with its current investments in those sectors, including in Shell, by the first quarter of 2023.

“We will stand up against Shell and continue to expose its hypocrisy,” said D’Sa. “They claim to be committed to a just transition towards renewable energy, yet continue to destroy the health of our oceans. We don’t want any oil washing up on our beaches, especially along the Wild Coast.”

Dated consultation

Shell media officials in the United Kingdom did not respond to queries about the growing opposition to its survey plans. However, following a request to environmental consultancy SLR, Shell South Africa provided a copy of its final environmental management programme for the exploration survey. The 548-page document, dated June 2013, does not appear to be available currently for public scrutiny.

Shell also provided a standard “media responses” sheet in which the oil company says “a full stakeholder consultation process was undertaken … for this project in 2013”. This process included publishing a background information document in four newspapers and a series of “face-to-face engagements, which included three group meetings (in an ‘open house’ format) in Port Elizabeth, East London and Port St Johns.”

In response to concerns about how underwater blasting would affect the marine environment, Shell maintained that “the impacts are well understood and mitigated against when performing seismic surveys. This is supported by decades of scientific research and the establishment of international best practice guidelines.

“There is no indication that seismic surveys are linked to (whale and dolphin) strandings.”

Shell further asserted that establishing a 500m exclusion zone around the sound-blasting ship “guarantees that no animals will come into the near vicinity of the sound source … If any animal enters the exclusion zone, operations are immediately shut down.”

It did not explain how observers could detect marine animals not easily visible from the surface during daylight or at night, but suggested that sound levels could be ramped up slowly to alert marine animals to “gradually move away from the sound source”.

Significantly, in a recent presentation to a South African conservation science symposium, international fish bioacoustics experts Anthony Hawkins and Arthur Popper pointed out that there are still “major gaps in our knowledge” about the impacts of underwater noise, particularly the more subtle biological impacts, the effects of underwater particle motion and whether current guidelines to regulate noise in different parts of the world’s oceans are still appropriate.