South African water polo is rising from deep waters

Participation in the notoriously underfunded sport has mostly been restricted to players from elite former all-white schools. But being part of Team SA for the Tokyo Games has the potential to chan…

Author:

20 November 2021

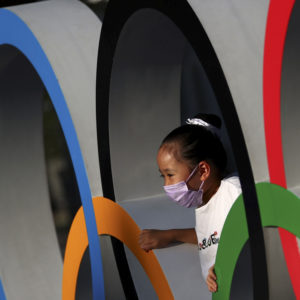

With disconcerting losing margins of 33-1 and 29-4, one could be forgiven for being surprised by the broad smile on the face of South African women’s national water polo coach Delaine Mentoor when the Tokyo Olympics came to a close.

As South Africans winced while watching the regular drubbings on TV – after four matches in the preliminary round, the South African side had scored seven goals and conceded 97 – Mentoor was celebrating other sorts of victories. Her self-funded side were never going to beat the fully professional teams they were up against in the Japanese capital. But simply competing at the Olympics was a triumph in itself.

The founder of the modern Olympics, Pierre de Coubertin, said: “The most important thing in the Olympic Games is not winning but taking part; the essential thing in life is not conquering but fighting well.” And while these sentiments don’t always sate the appetite of medal-hungry South Africans, when it comes to the nation’s water polo teams, they couldn’t have been more apt.

For the women’s side, it was a first appearance in Olympic history, whereas the last time the country’s men competed at the Games was pre-isolation in 1960.

“Sitting at the athletes’ village and watching my team walk out at the opening ceremony was definitely a highlight for me,” says Mentoor. “That was tear-jerking stuff, like, those are my ladies and they’ve worked so hard to be here. It was just incredible to see them on that screen … because I knew what it took for them to get there.”

Related article:

What it took was years of training and raising funds to pay for their own training camps while simultaneously juggling full-time jobs or studies. In all this time, there was also the uncertainty over their inclusion in Team SA by the South African Sports Confederation and Olympic Committee (Sascoc).

The team had qualified through a continental berth – a path to the Olympics that Sascoc previously denied. With qualification criteria being relaxed this time round, the way was opened but still not confirmed for a long time, leaving the teams on tenterhooks.

“We had our training camps, our build-up, every little thing, but everyone was waiting for that bomb to drop that water polo wasn’t going to Tokyo,” says Mentoor. “We had about six training camps … but we didn’t have our pre-departure camp, and we had zero internationals. Our first international game was against the European champions [Spain] at the first game at the Olympics. For some players it was the first ever senior tournament they’d entered.

“All training camps and everything was self-funded. The ladies had to have high-performance swimming coaches. They paid for that themselves. Their conditioning coaches and gym, they paid for themselves. So that was our preparation, all self-funded to get us here.”

A tough journey

It was a similar scenario for the men’s side. “The journey was tough, filled with many uncertainties and doubts,” says national men’s team captain Lwazi Madi.

“Despite the training camps being self-funded, a lot of the players knew that this was going towards a greater cause. We knew just how important going to the Olympics was for us not only as players, but to also inspire players in South Africa to push hard and realise that you can achieve your dreams.

“We hope that we can continue to inspire younger generations in water polo. We also helped alleviate the costs by having fundraising events such as golf days in the different provinces, which helped pay back some of the money the players had spent on training camps.”

The men’s side also went down by some hefty margins, eventually conceding 116 goals in total and scoring 20 in their five group games. “I feel that a lot of South Africans won’t understand the time and effort that we as players put in towards training for these Games,” says Madi, reflecting on the results. “I also feel that South Africans may not understand the difficulty of not being funded to attend more competitions overseas.

Related article:

“One of the biggest challenges South African water polo faces is our geographical location. We are one of three countries in Africa that play water polo, whereas in Europe many more countries compete against each other and their close proximity to one another makes it easier for them to participate more frequently, which ultimately improves their standard of water polo.”

So it was indeed a triumph for the South Africans standing on the pool deck in Tokyo, producing some competitive periods of play and managing to score several impressive goals.

“It was a surreal feeling. It still feels like a dream to me, and I think for many others as well,” says Madi. “We never thought we would have the opportunity to attend the Games, and for a lot of us this was a big dream which we all wanted to achieve but didn’t think it was possible. I can still feel the pride and passion I had when I sang the national anthem with my teammates for the first time. It is a memory I will cherish always. It was also special for me because I was the captain of the team and I felt proud to be a South African.”

The bigger score

For Mentoor, there were plenty of goals achieved in the process. “Coming in, it was overwhelming and daunting at the same time. Team-wise we knew we were going to be up against the best. Our first game was against the European champions, so I mean, hello giants, we’re the little people from Africa,” she jokes.

“But as much as it is daunting, it’s also exciting. For us to put that next to our names and compete against them … and physically, when you look at one-on-one movements, nobody was thumped or brutally hurt. It was physically matched so that in itself was amazing, that we were able to physically stand our own at the Olympic Games. That’s incredible.

“I really wanted to make sure that we grew from each game. If we were better each game compared to the previous game, that for me was important and we ended off better from the first game to the last. We were incredible in our last game. It actually felt like a win.”

Related article:

The teams also managed to gain the attention of international coaches and officials, with some players even being approached to possibly play in overseas leagues. “We’ve had really good feedback from the [international water sports federation] FINA athletes’ representative. They want to help us. They want to get our teams over to have training camps. They want to know what they can do because they can see the potential. They see how physical we are, they see what we can do with six months and they believe that with so much more help we can go far, so that’s a really good positive for us. We’re getting people coming to us and saying, ‘Let’s help you. Let’s help you get resources as well.’

“That’s already so comforting, knowing that people see the talent we have and what can be done with this group of ladies and they want to help us. That’s never been something that we’ve had in the past, people coming up to us and saying, ‘Jeepers, your goalkeeper is extraordinary.’”

The need for change

While international assistance will be a massive boost, plenty will need to change for the sport to forge ahead in South Africa. The feedback from players and coaches at the Games was overwhelmingly positive, but there are many reports of infighting, power-grabbing, selection fights, mismanagement and a parent body in Swimming South Africa that seems completely detached from the sport.

Then, of course, there are the numerous allegations that have surfaced of sexual assault in water sports. It is particularly concerning that many of these cases have taken place at school level. Most recently, the suicide of a 16-year-old student at a prestigious school in the Eastern Cape was allegedly connected to such abuse. And while these cases are at least now being reported and dealt with more effectively than in the past, the implementation of safeguarding policies in South African sport is well behind where it should be.

For progress to be made, the image of water polo as a predominantly white sport reserved for the private school elite will also need to change. Asked about this stereotype, Madi reckons: “When I first started water polo, there were not a lot of Black players in the game. I do feel like that has improved since I left high school, however, I do feel like there could be more diversification in the sport.

Related article:

“I encourage all players of colour to get out of their comfort zones and try new things, as you never know if you’ll like something without trying. Perhaps schools could encourage more players of colour to partake in the sport. I am hoping that Black players would have seen me on TV and felt inspired. It’s already tough having these stereotypes surrounding Black people and swimming, and I am here to show them that this isn’t the case.”

While Madi went to a private school himself, matriculating from St Stithians in Johannesburg, it was a different story for Mentoor, who also believes things are changing in the sport.

“I wasn’t in a private school. I went to school in King William’s Town in the Eastern Cape. Yes, water polo has always been labelled as this [pre]dominantly white sport and [pre]dominantly for the wealthy. But I’m telling you, in the Eastern Cape there are schools that play it with little to no resources and it’s available to them.

“I do think that it can become more accessible. I think it can be promoted more, but I think the Olympics and seeing our teams there can help that, with people realising what the sport is. The amount of messages I got from people saying ‘my daughter is just starting out – do you have words of encouragement’, or ‘thank you so much for what you’re doing’. Seeing a woman of colour up there coaching inspires them, so I really hope that this motivates people to want to join clubs because there are so many clubs that are available in every single region.”

Related article:

Not only was Mentoor breaking barriers in Tokyo in being a Black woman, but also as the first female coach in Olympic history and, at 28, the youngest too. But now the focus needs to move on from Tokyo to preparations for the next Olympics in 2024. Sascoc has maintained its broader selection policy that now includes qualifying through Africa is here to stay, so plans can be put in place for the Paris Games.

While funding is still likely to be scarce, motivation levels are high, which will hopefully lead to the necessary changes being made so that the gaping disparities between the South Africans and their rivals can be overcome.

“After attending these games in Tokyo, I am more motivated than ever to go for the Games in Paris,” says Madi. “We had a relatively young team at the Games, so I’m sure many players will be hungry for Paris.”

Mentoor agrees. “With the goal being 2024 and using this Tokyo experience now, I can tell you these girls are incredibly inspired. They just want to go back and use what they’ve learned here. They just want to take it back to their clubs, their teams that they coach, the squad members that weren’t here. Go and show them and teach them and tell them about what they’ve experienced, so the inspiration levels are extremely high.”