South African parties jump to the right on migration

As the 2019 general elections approach, South African politicians are adopting the global anti-migrant rhetoric.

Author:

3 December 2018

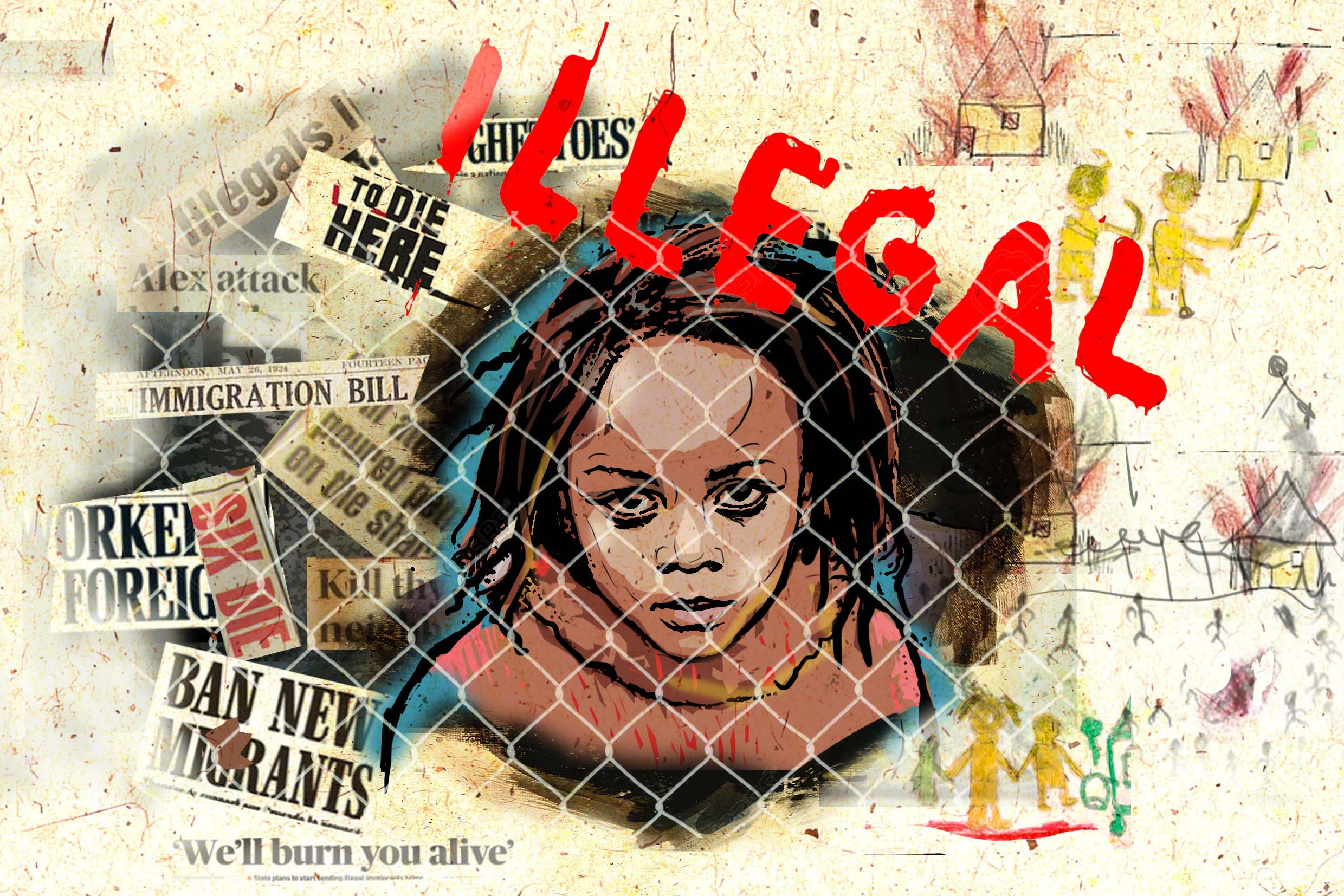

It has become clear in recent weeks that mainstream political discourse in South Africa is following the global swing to the right, with the issue of migration at the forefront. At the heart of the established political parties’ rhetoric is a deep contempt for anyone perceived to be a foreigner, alongside a habit of politicians making migrants scapegoats for what are, in essence, the failures of the political class.

Wildly exaggerated statistics regarding migration are often offered as fact. In the context of systemic impoverishment and unemployment, and sporadic xenophobic violence, this rhetoric is extremely dangerous.

As previously reported by New Frame, the DA has made migration one of its key issues in its election campaign. Floyd Shivambu from the EFF has also made xenophobic statements. At the same time, the ruling ANC has been driving policies around migration that would exclude mostly impoverished black African migrants.

Related article:

The White Paper on International Migration seeks to attract highly skilled labourers under the guise of security and stability. With this in mind, the proposed policy seeks to introduce a points-based work permit system to attract skilled workers and grant critical skills and business visas to migrants. Despite South Africa’s commitment to make movement on the continent easier, such proposed policies institutionalise negative attitudes towards low-skilled, vulnerable and impoverished African migrants and asylum-seekers.

Applicants for asylum-seeker and refugee status already face increased challenges in accessing documents to live and work in South Africa. In its most recent annual report, the home affairs department celebrated a steep decline in the number of successful asylum-seeker and refugee applications. The department said this was proof that after its interventions there was “a reduction in the abuse of the asylum-seeker regime”.

Related article:

NGOs that offer support to migrants, including Lawyers for Human Rights and Amnesty International South Africa, have criticised the department and its refugee reception offices for what they perceive to be a “copy-and-paste” response to many asylum-seeker applications. This supports some of the fears raised by critics of the white paper and the Border Management Authority Act, which seeks to militarise South African borders in an attempt to keep impoverished, unskilled people out of the country.

Poisonous global trend

Globally, the politicisation of migration, and by extension that of unlawful immigration, has given rise to nationalistic, anti-immigrant platforms that allow politicians to sow fear and division among people. In the United States, President Donald Trump has sent more than 5 000 troops to the country’s southern border in anticipation of the arrival of a large caravan of migrants from South and Central America.

In South Africa, these attitudes have seen politicians shift responsibility and blame migrants for a range of issues, including high levels of crime. Last month Health Minister Aaron Motsoaledi blamed the abysmal conditions at state hospitals on “foreign nationals”. But when asked for the statistics to substantiate these claims, Motsoaledi’s spokesperson Popo Maja said the health department didn’t keep those statistics and that the Gauteng health department would be able to “give a better picture”.

Motsoaledi is, of course, not alone in harbouring contempt for migrants. City of Johannesburg Mayor Herman Mashaba has continuously made xenophobic statements in an attempt to blame migrants for the city’s woes. Mashaba has blamed crime in the inner city on “illegal immigrants”. Last month, he staged his first citizen’s arrest of an informal trader and deflected criticism on Twitter by citing his concern for public health and not allowing “people like you to bring us Ebolas in the name of small business”.

Related article:

Academic and former political prisoner Raymond Suttner recently wrote that instead of addressing societal problems in good faith, politicians such as Motsoaledi and Mashaba resort to demagoguery. In a piece on Motsoaledi and the scourge of xenophobic rhetoric Suttner wrote that right wing populism, and fascism, aim to divert popular anxiety and hostility towards vulnerable scapegoats rather than to try and address the real causes of social problems.

“By diverting attention towards an imaginary cause, Motsoaledi feeds into widespread prejudices against foreign migrants … Another element of Motsoaledi’s statement may seem innocent and of purely professional interest, when he raised the concern that the overcrowding may lead to spreading of disease. This could be taken as the normal fear of a doctor and a minister of health, if it were not for the discourse around foreign migrants which perpetually associates them with disease, threats to our health and wellbeing, referred to as carriers of Ebola …”.

At the launch of an affordable housing project in Turffontein, south of Johannesburg, last month, Mashaba said the housing project would cater only to South Africans. This in stark contrast to the ethos of the Bill of Rights, which states: “Everyone has the right to have access to adequate housing.” The Daily Maverick quoted Mashaba as saying: “The units are only [to be] occupied by those legally permitted to occupy the units – our poorest residents.”

Dehumanising vulnerable people

Xenophobic rhetoric is exacerbated by the fact that neither the home affairs department nor any other institution can definitively state how many migrants there are in South Africa. There have been widely irresponsible estimates, such as those made by Police Commissioner General Khehla John Sitole during the police department’s release of the annual crime statistics. According to Sitole, there were an estimated 11 million undocumented people living in South Africa.

South African and international media have contributed to the widely inaccurate claims, with the New York Times, the BBC and Reuters using figures of anywhere between 2 million and 5 million people. The home affairs department was unable to provide clarity when asked by New Frame. The most realistic figure, 2.2 million, is based on figures generated from Census 2011.

Unreliable figures pave the way for dishonest politicians to take advantage during electioneering, blaming anything from unemployment and crime to a lack of services on an imagined threat posed by the high number of migrants in the country.

Related article:

Entirely fabricated numbers are also very common. Michael Neocosmos, a leading scholar on xenophobia, described the scourge of xenophobia as similar to racism in his seminal book From ‘Foreign Natives’ to ‘Native Foreigners’: Explaining Xenophobia in Post-apartheid South Africa.

“The use of the term ‘illegal’ is often employed in conjunction with ‘immigrant’ to intensify their dehumanisation. This discriminatory treatment is time and again justified on the basis of the economic and social crises facing South Africa where about half of the population is said to live in poverty. This has been said to have resulted in the deepening social exclusion of and violence towards ‘foreigners’,” writes Neocosmos.

The xenophobic statements made by politicians such as Motsoaledi and Mashaba can only be viewed as direct attempts to dehumanise some of the most vulnerable people in our society in the name of other vulnerable people. Their statements, not migrants, should be treated with the same disgust as the xenophobic and racist statements made by Trump in the US.