‘Sons of the Sea’ and the tentacles of colonialism

John Gutierrez has crafted Black characters who understand and think about the world around them in a film rooted in the Cape’s history and its impact on the present.

Author:

19 August 2021

On the Cape coast, brothers Gabriel and Mikhail find two bags of abalone and a dead man in a hotel room. They take the loot into the shadows, under a sliver of a moon, and are tracked down by a financially burdened official named Peterson. Gabriel is wide-eyed, virtuous. Mikhail is jaded, nihilistic. In both, there are reflections of all of us. Cornered, the brothers turn violently on each other. But they also shoulder one another, softly and seamlessly, while trying to maintain their tenuous clasp on survival. Until finally, they truly see the other as their trajectories diverge forever in this unfolding tragedy.

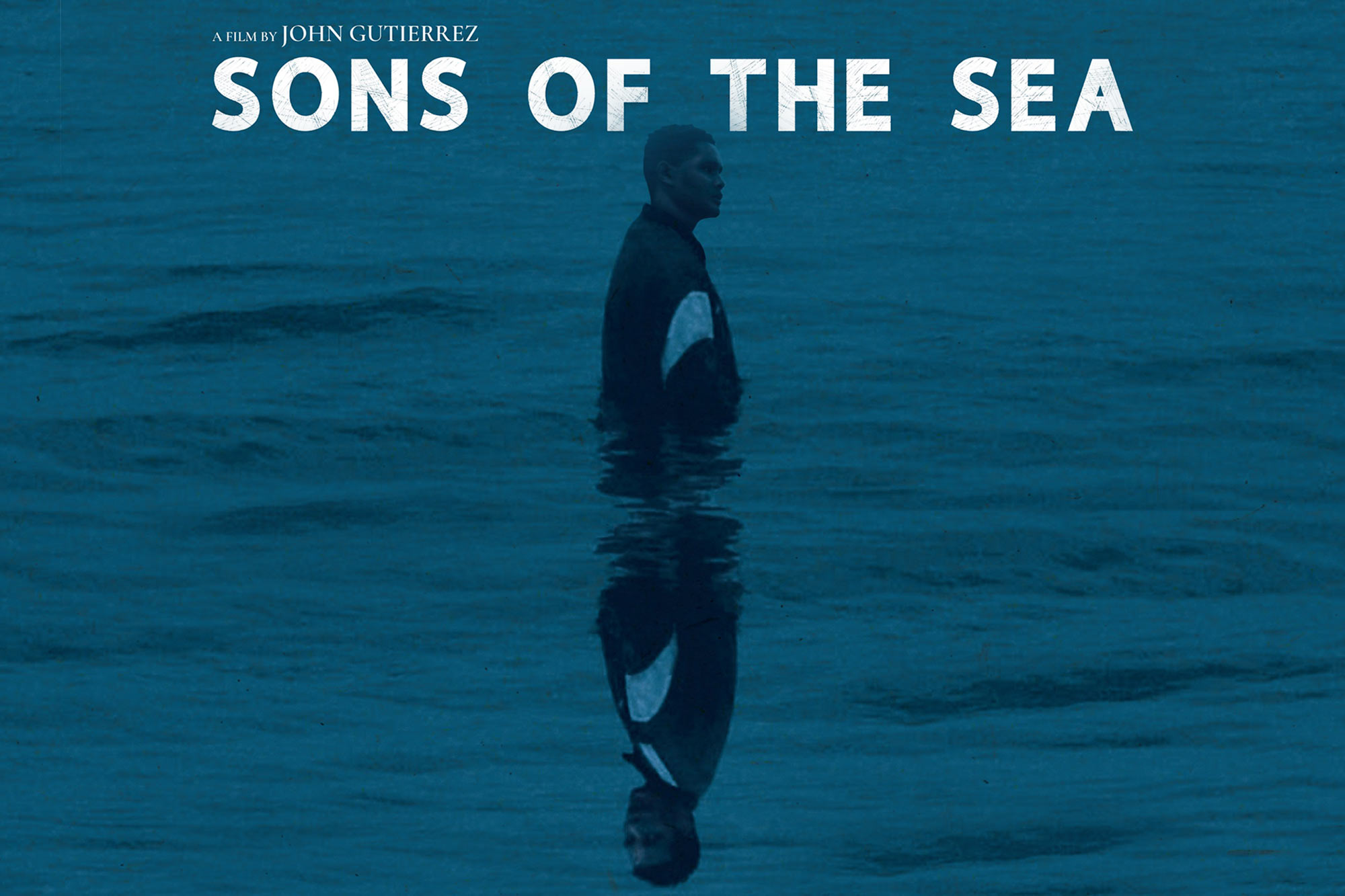

This is the world that John Gutierrez has crafted carefully with the feature film Sons of the Sea. Inspired by both Mexican folktale El Mechudo and John Steinbeck’s novel The Pearl, he showcases with complexity the long-reaching tentacles of colonialism, in a globally resonant story of land, home, family and freedom that is refreshingly devoid of stereotypes.

“I just wanted to make something that I would love to watch,” writer and director Gutierrez says at a cafe in Woodstock, Cape Town. The Californian filmmaker from a Mexican-American family is now based in Cape Town. He found resonances across continents.

“One thing I realised,” he says, “is that they’re very similar, the Mexican-American culture and the coloured culture here. We do the same shit, we do this thing where we’re like crabs in a barrel and we all bring each other down. So it is very much a lived experience for me. It is this thing that I know intimately.”

The feature, which won Best South African Film at the recent 42nd Durban International Film Festival, is shot in documentary style. Made with a small cast and budget, the team is filled with people who have deep roots in the Cape. Gutierrez aimed to give the story a “social realist naturalism feel”.

The fynbos, sand dunes, proteas, unending ocean and clouds make a pristine backdrop for a dark story.

The past and parallels

Set in Ocean View and Kalk Bay, the film introduces politics from the start. As the brothers walk through the gentrifying neighbourhood, they comment: “The fuckers won’t stop building.” Gutierrez says this is an ubiquitous Cape Town reality. “These characters are from this place, land, and sea, generationally, ancestrally and it’s an encroachment on them personally,” he says.

Along with culture, the director notes parallels between the respective colonised histories and creole communities of South Africa and North and Central America.

“Most of these people have very similar families to me, families where you have uncles who are carpenters, cousins who are in gangs. There’s this mirror of the two cultures [Mexican-American and those classified as coloured under apartheid]. And so it was interesting to take a story inspired by El Mechudo and bring that here to a city on the other side of the world, and transplant that story, and the story of my own culture.”

References to history’s imprint on the present in the film are quietly impactful. At several points, we gaze into a hotel painting of settler ships, colonial warfare, rifles and dead slaves in a gilded frame.

“That specific painting was hanging in the hotel when we got there,” says Gutierrez. “There’s so much of the legacy of colonialism that you want to communicate… As a filmmaker, you have to find a subtle powerful way of doing that. And for me, that painting says it all. It magically foreshadows the tragedy of the film.”

The colonial-era painting becomes a motif that is never commented on but is seen by all, and its symbolism resonates deeply with the characters’ lived realities.

Hunter and hunted

From the very beginning Gabriel, tenderly played by Roberto Kyle, is pictured with his cue cards, studying, thinking and taking pictures. Gutierrez describes him as “this precocious young man who likes to read, who likes philosophy, who’s studying for matric”. Gabriel’s partner Tanya is an “anti-femme fatale”. Played by Nicole Fortuin, her character adds a necessary levity, and their romance reveals a young couple destined for and dreaming of more.

Gutierrez uses several devices deftly to serve his narrative. When Gabriel struggles to pick up the heavy black bags of abalone, taken from a dead man, he drops a cue card. Written on its surface is the line “All world processes are made up of two forces”. It becomes a profound plot clue. “It’s a description of good and evil, the forces of darkness and light,” says Gutierrez. “The two brothers and the duality that relationship represents.”

Featuring an entirely Black cast, the director represents multiple different experiences in the same lifeworld. Speaking to the website Africa is a County, Gutierrez mentions that the initial funders “recommended three white male actors for the role of Peterson”. The team declined this offer, wanting “to decentralise whiteness in the film” and because “the official needed to come from the same world as the boys … It always hurts more when your own enact violence on you, we know that, and there’s a difficult, complicated history of how that happens.”

Beyond stereotypes and surface, each character is given a complicated humanity. In a beautifully crafted scene, government official Peterson is hunched over on a hotel couch, smoking and making notes while sharing the story of his father, a fisherman from Simon’s Town who was driven out by the forced removals to a landlocked area, and started hunting.

Brendon Daniels, who plays Peterson, delivers a stirring speech through wrinkled smiles laden with memory and loss, recalling the days when the water was crystal clear with no seaweed – days when abalone was abundant and could be picked straight off the beach for family dinner; today a scarcity.

Peterson is financially and emotionally distressed, so much so that his dead wife is still his phone screensaver. At night, his young son Adam cries for his mother as Peterson tries to console him, voice wavering between desperation and futility.

Called to action, he takes out his father’s old rifle and resolves to find the abalone. Once used to hunt for food, it will now be used to hunt his own. A defeated man with a big gun, Peterson cuts a tragic figure.

Lenses and dream portals

Another of Gutierrez’s skilful choices is his use of the lens as a metaphor on perspective. We feel Gabriel’s playfulness through his camera lens as he snaps photographs. We sense Peterson’s deadly intention looking through his rifle at his target. And we experience Adam’s curiosity when we peer through his binoculars at his grief-stricken grandmother stumbling drunk on a sand dune.

Gutierrez places viewers within the characters’ perspectives. Through their chosen instrument, we understand their intention – and at any point, could be any one of them.

Related article:

From the pointed realism of these lenses, the film moves into unconscious dreamscapes. In a visually striking nightmare full of foreboding, Mikhail is waist-deep in the ocean before he submerges. In Gabriel’s dream, he gets pulled under and the ocean plateaus again, flat, unending and still. The seagulls circle the dark sky mirroring the sea. A body floats to the surface, motionless.

“The imagery is inspired from this Mexican folktale called El Mechudo,” Gutierrez says, “where a diver gets his hand caught in a giant oyster and never resurfaces. Trapped at the bottom of the bay forever, he haunts the bay. I wanted to capture that. It’s like some monster has taken him [Mikhail]. But also the sea has taken him, and the abalone that he’s intent on having has consumed him, the evil around it, the darkness around it.”

Crabs in a barrel

Mikhail, played by Marlon Swarts, is the hardened, fearless instigator who, on seeing a recently dead man, casually calculates the abalone loot to be worth about R100 000. He issues the instruction to get black bags and shakes his nervous brother Gabriel into action. Unlike his brother, Mikhail is unfazed through most of the ordeal, with a higher capacity for violence and a stronger stomach for the bitter cards life has dealt. Their lives provide foils for each other, alternate possibilities and diverging paths rooted in the opportunities they were given.

While Gabriel has school, a job and a girlfriend, all Mikhail has is this hustle, these two bags, this future. “Jy het dit gesteel (you’ve stolen it),” says Gabriel, referring to the dead man’s abalone. And this is where we’re gifted with Mikhail’s powerful rebuttal. Affronted by this accusation, Mikhail scoffs at the idea that he’s the one stealing anything.

Holding up the abalone, he explains that it came from “onse waters af, ons fokken land (from our waters, our fucking land)”, that these waters and this land was stolen from them. Before the houses had sprung up along the shores, their people lived here. “Ons lewe uit die see uit. Die is onse kos (We live from the sea. This is our food.).”

Related article:

Reflecting Gutierrez’s intention, the characters are crabs in a barrel, pitted against each other by structural oppression. Mikhail’s retort is steeped in political insight and the injustice of scrambling for resources that should be yours.

“It’s a truth I feel audiences need to be reminded of,” says Guiterrez. “It’s important for me that these characters are intellectuals and they think deeply about where they come from.”

Of Mikhail, he adds: “He’s just not some greedy wannabe gangster. He’s political. He knows what his motivations are. He knows why he’s in the place he is. And he’s frustrated with it and angry about it.”

The pink sky and the huge eyes

“I wanted everyone to be rooting for everyone,” says Gutierrez of the final scene.

In the light of the pink sky with tangerine-tipped clouds and tall-shadowed shore, Gabriel walks away. For a second, he seems to look directly at Peterson’s child, who appears to gaze back with huge eyes, set against the same pink sky. And the audience is left to wonder, do they actually see each other?

“That’s intentional,” Gutierrez says. “Psychically they are the same person. But we hope for him [Adam]. His future is unwritten. And we are partly responsible for that future. So that’s what I wanted to leave the audience with.”

A little boy alone at the ocean is the final image, orphaned and destitute as the waves crash behind him. This end shows us a brutal similarity, a repetition of circumstance, place and struggle, as we come full circle.

Sons of the Sea screens in South Africa from 13 September.