Small solutions to SA’s big problems

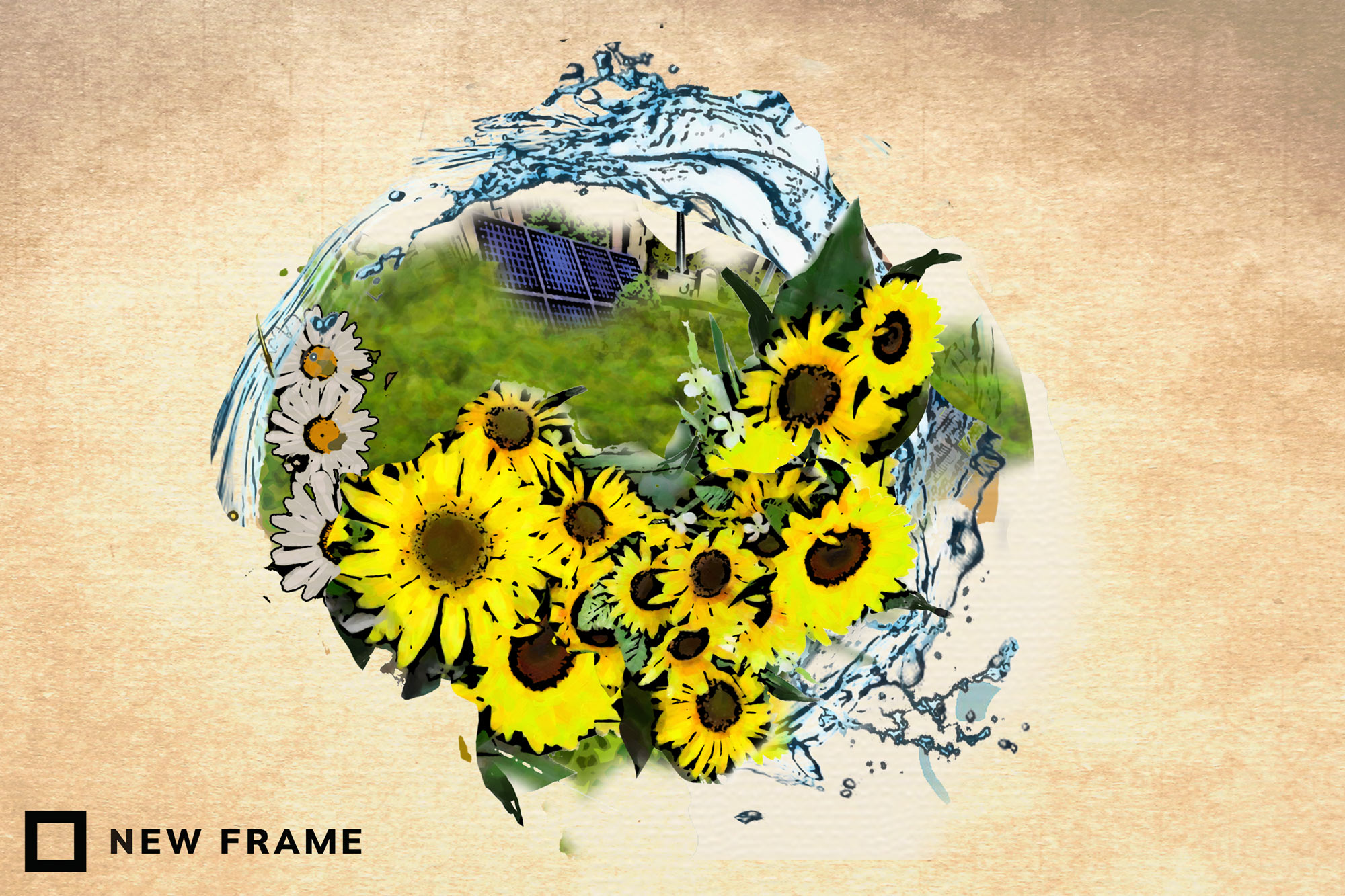

Localised projects such as SaliTuba in KwaZakhele give residents a way to feed themselves and their communities, develop skills and create sustainable livelihoods.

Author:

20 December 2021

Before joining a unique water, vegetable and solar energy collective, Lungile Tyali, 48, from KwaZakhele township in Gqeberha, Eastern Cape, was living below the poverty line.

Tyali says he had hardly any skills that would help him develop and distance him from poverty, and his abiding memories are of his struggle to make ends meet.

The SaliTuba project launched in 2017, with support from Nelson Mandela University’s Centre for Integrated Post-School Education and Training and its department of development studies.

Related podcast:

SaliTuba is situated on a small square of land that used to house a so-called gap tap – single taps installed by the apartheid regime to serve 35 surrounding households who then had no running water and had to line up to collect water in buckets. The 120 municipal gap taps in KwaZakhele fell into disuse once the houses got running water and were removed, and the parcels of land on which they stood have become public spaces just waiting to be repurposed.

About 120 000 people live in KwaZakhele, in 25 000 households. Unemployment is high at 50%.

Tyali joined a group of people who established vegetable gardens and built a steel roof to house 14 solar panels on former gap tap land. They channeled waste water from two homes nearby for irrigation and, before long, members of the group were feeding their families with the income they made selling vegetables. “We were unemployed and had no skills, but after this project came we learnt and gained a lot,” said Tyali.

Delayed agreement

SaliTuba is part of the Transition Township project, which wants to move away from coal and fossil fuel as well as towards a more egalitarian economy. It uses a model of neighbourhood cooperatives that produce energy and food, and recycle waste.

Janet Cherry, a professor of development studies at Nelson Mandela University, has been working with Transition Township for several years and says many townships have underutilised assets.

“KwaZakhele is full of empty factories, abandoned school buildings, open plots of land and a big decommissioned coal-fired power station, so there’s infrastructure there that can be repurposed,” Cherry told a recent seminar at Rhodes University’s Neil Aggett Labour Studies Unit.

Related article:

However, the cooperative is still trying to iron out a foolproof way to sell the electricity it generates back to the grid.

“We are not looking at a model of a sustainable village which is completely self-sufficient, off-grid. This model is premised on feeding [energy] into the existing municipal grid, selling food and creating local markets,” said Cherry.

The current problem the cooperative faces is the delay in concluding an agreement with the Nelson Mandela Bay municipality on the sale of its electricity, a delay the members cannot understand given the continuing load shedding.

If the municipality did buy the electricity, SaliTuba would be a shining example for other townships. “Our project could even have the potential to help informal settlements because it focuses on water, food and energy,” said cooperative member Xolisa Bhe, 26.

A liberating force

Another member of the group, Lubabalo Mkiva, 27, says the municipality told them at first that the project was not generating enough electricity for them to sell. “They have not helped us with one thing and that is a great challenge. They came here once talking about bringing us JoJo water tanks, but nothing happened after [that],” said Mkiva.

The cooperative was contemplating selling electricity to a private company when four of its solar panels were stolen. “We were waiting to sign with a big company, which was going to buy electricity then resell it to the municipality. But four panels were stolen and this forced us to remove the remaining 10 for safekeeping,” said Bhe.

This spurred the SaliTuba members to set up a neighbourhood watch WhatsApp group to keep an eye on the project. “We want to build a fence around the project to help safeguard the resources here. There is a lack of support from the councillor to help us. We want to do more from this project and would like to ask for support from companies,” said Mkiva.

Related article:

Technology is a liberating force if it is socially organised, according to SaliTuba. Once its members are able to sell the electricity the project generates, many will earn a living for the first time. This is in addition to the decent work of combating climate change and providing affordable and healthy food for the community.

Cherry said South Africa is in the grip of an electricity crisis, highlighted by Soweto residents protesting against power cuts and calling for a flat rate of R200 a month for electricity, as well as the continuing campaign to uproot the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy. Uproot the DMRE is demanding a rapid and just transition to a socially owned supply of renewable energy, electricity for all and one million new jobs in the renewable energy sector.

Working-class and impoverished communities cannot afford generators to help them cope when load shedding hits and small local projects such as SaliTuba could be the energy alternative they need.