Small businesses die tragic slow death in eMvelo

The Covid-battered economy of this Mpumalanga town is taking another hit as the local municipality imposes electricity shutdowns because of a lack of sufficient supply.

Author:

14 April 2022

eMvelo, a town in Mpumalanga with an estimated 15 000 residents, has been desperate for its economic activity to pick up after the Covid-19 pandemic. The economy of the town, formerly known as Amsterdam, is mainly tied to forestry and agriculture.

Though it was beginning to show signs of life with a new shopping centre completed late last year, its infrastructure is crumbling and it has been plagued by electricity outages that were imposed by the Mkhondo local municipality in February 2020. These are in addition to state power utility Eskom’s load shedding, which hits South Africans frequently.

Business owners and residents are concerned that the sporadic supply of electricity is further pushing eMvelo into a state of collapse. Daily, different sections of the town do not have power for up to 10 hours as the municipality imposes what it calls “load reduction”.

Sometimes the municipal outages last much longer, like one in December that left residents without power for a week, their food spoiling and rotting. As a result, the only shop occupied in the new centre is a KFC fast food franchise, and its grand opening on 16 December was delayed for several hours by yet another power outage.

Corene van der Lith, 55, has been running the Robert Burns Inn, one of only three businesses that offer accommodation in the town, for 21 years. The establishment has 14 rooms and a restaurant that serves food and drinks to non-guests too. “I hope they will remember to put us back on after 2pm,” she said after the electricity in her part of town had been off since 11am and she had been forced to rely on a generator.

“We’d be lucky to have electricity from 2pm onwards, because when it comes back it will trip. On top of the three hours of electricity reduction, every day they score an additional hour and a half with all the tripping.”

Van der Lith said it has become incredibly difficult to run her business, and she has been forced to cut down on her opening hours to reduce the wage bill for her seven workers. “Every day we use about 50 litres of diesel and diesel is so expensive now. The amount of diesel that I use per month makes me totally depressed. I spend between R13 000 and R15 000 a month on it.”

She lamented that she has to pay twice for electricity: for municipal power and for diesel. “Our problem is that it does not help me to work my butt off and I’ve got two accounts to pay. It is a losing battle. [Running a business] is hard, but it doesn’t have to be this hard.”

Shrunken livelihoods

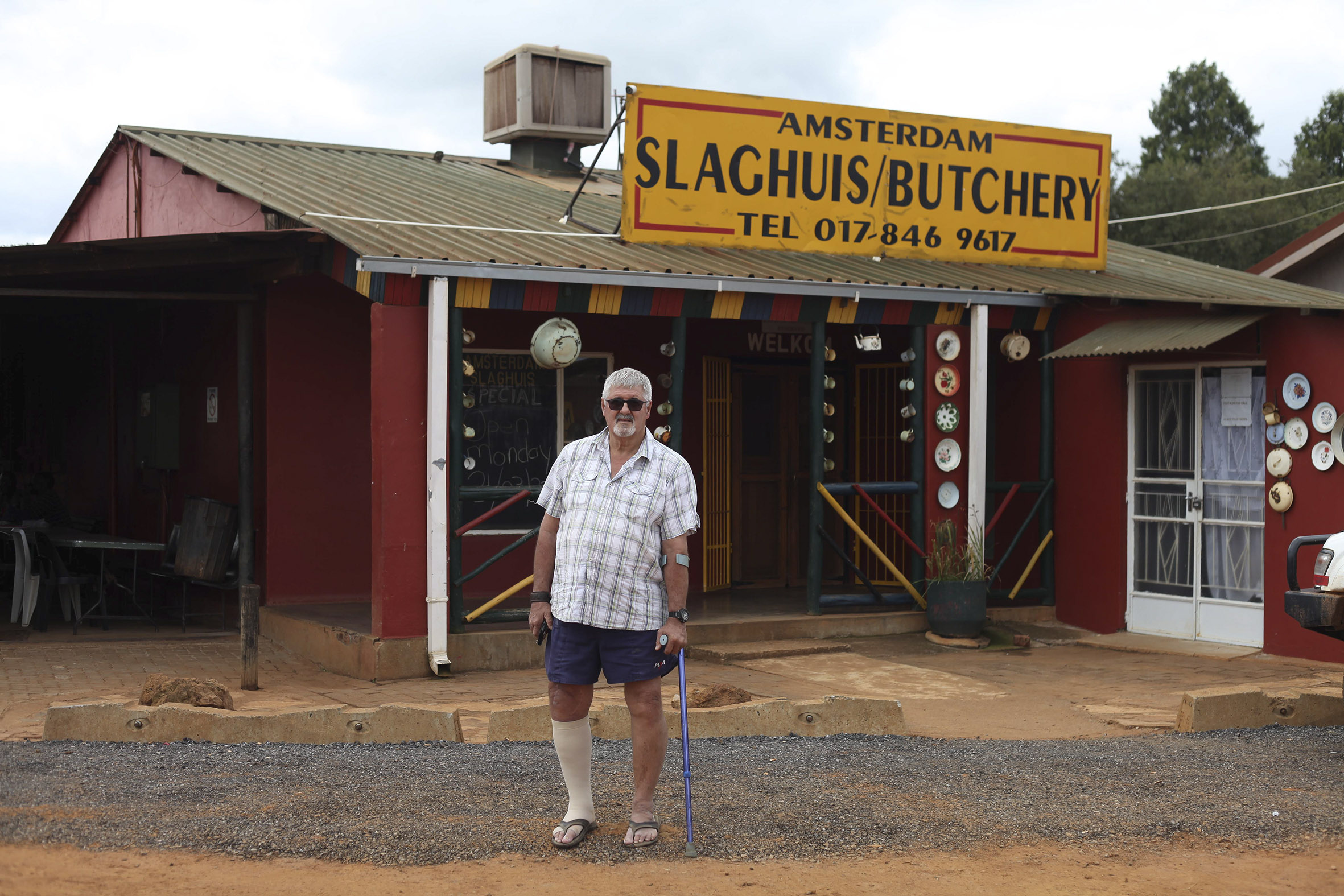

Giel Coetzee, 58, runs a carpentry business that is entirely dependent on electricity. He does not have a generator. Before the load reduction Coetzee would manufacture 1 500 doors a month, but this number has shrunk to 300. As a result, he has cut his workforce of 50 people to just seven. “Just last week I was contemplating closing down the business because I cannot keep surviving like this,” he said.

The planks that Coetzee uses for the doors are supplied by Nelson Makhathini, 28, who employs 13 people. He, too, does not have a generator. He explained that his initial target was to finish at least 10 cubic metres of planks a day, but his workers can only get less than half of that done.

“To be honest with you, this makes me so sad. When I go home, I see a lot of my peers sitting around the streets and no one has a job,” Makhathini said. “Then, when young people like me are trying to create employment, our government fails us like this. A lot of businesses are closing, but we wake up each and every day to make sure that these doors of employment are open.”

The shortage of electricity also hampers the work of local doctors. Apart from a public clinic, the town has two private medical practices. One doctor said he has had to send patients home when, for example, he couldn’t make a proper diagnosis because X-rays could not be taken.

And when the electricity comes back on, electrical appliances are often damaged. An official in the local magistrate’s court, who wanted to remain anonymous, said the court could not function properly because recording equipment is often damaged. This forces officials to manually write down what each person says in the courtroom.

“If there is a trial with five witnesses, you can just imagine the workload of the evidence leaders who cross-examine different people, and maybe the accused are three or four people … the workload is a nightmare,” the official said.

The outages also affect processes like bail applications, leading to people accused of crimes being kept longer in custody. “Let’s say the machines are working. While the defendant is still busy giving his version of events, the electricity goes off,” the official said, adding that the court would be left with no choice but to postpone the matter for several days.

“People would say this court is not functioning, justice is not served. They do not understand how many times the magistrate keeps saying the machines are not working and we cannot proceed,” said the official.

Blame Eskom

A source working for the municipality, who also asked to speak on condition of anonymity, blamed the power outages on Eskom’s chief executive, André de Ruyter, saying they had become much more prevalent since he assumed his position in January 2020. Before De Ruyter’s appointment, municipalities would pay levies if they exceeded their allocated megavolt amperes (MVA), but now they get cut off.

In the case of eMvelo and Mkhondo, the source said, the amount of electricity supplied used to be sufficient until the population grew and more RDP houses were built.

The municipality’s media liaison officer, Robert Kubheka, said Mkhondo receives a minimum of 18MVA from Eskom, whereas the municipality uses up to 23MVA. “We’ve got all the resources that are needed by Eskom to increase our MVA. Our plan was to increase our MVA to either 30 or 40,” Kubheka said. “If ever we bridge the agreement with Eskom of the [allocated] 18 MVA, then there are penalties that the municipality will have to pay.”

But the source said “negligence” by previous administrations is a key factor that has led to the municipality “borrowing” electricity. “When the contracted MVA became insufficient, the leadership at the time should have picked it up if they were people who are observant.”

In an interview in December 2021 with the Daily Maverick, when asked about some of the biggest hurdles he faced, De Ruyter highlighted the debt that municipalities across the country owe Eskom.

“We have also been unable to find a solution to ballooning municipal debt, in spite of efforts made by the political task team led by the deputy president,” he said. “The culture of non-payment has resulted in municipal debt now amounting to R42.5-billion, equal to 10% of our total debt. This is an unsustainable situation that needs to be resolved urgently, as Eskom cannot continue to fund delinquent municipalities.”

In response to a question in Mpumalanga’s legislature about the Eskom debt of the province’s municipalities in November last year, Busisiwe Shiba, member of the executive for cooperative governance and traditional affairs, said just 10 of them, including Mkhondo, owed R12.5 billion.