Silkscreening the pandemic

The print exhibition explores life in a world changed by Covid-19 through artworks that show us how individuals and communities have been shaped by the fallout from the outbreak.

Author:

8 June 2021

When discussing the social history of printmaking in South Africa and the work of his studio, Danger Gevaar Ingozi (DGI), Nathaniel Sheppard has an air of quiet pride. Together with Sbongiseni Khulu, Chad Cordeiro and Anaz Mia, he co-founded DGI in 2016. The multimedia print studio and gallery space, which is Black owned and run, is based in Johannesburg’s Victoria Yards.

Sheppard’s quietude dissipates when he describes “the fun restrictions” the brief for the studio’s screen-printing portfolio exhibition Home for the Holidays imposed on the 10 participating artists.

“Playful prompts, like limiting silkscreen options to only three colours, are usually only seen in university spaces and are often swept aside when working professionals need to start concentrating on developing their signature style,” Sheppard says.

Thoughtfully conceived and carefully curated, the exhibition, which opened on 27 April at the DGI studio and continues online, explores the sociopolitical, historical and economic implications of the pandemic in South Africa.

The studio focuses on building networks between Black artists and businesses in the printmaking industry, and Sheppard explains that with this exhibition, DGI was crafting a cocoon of sorts. They aimed to work collaboratively with the selected artists on developing their individual responses to the pandemic. In this sense, the exhibition stands as a reminder of how the pandemic made many creative enclaves possible, spaces that have been central to surviving this time.

Journeys of the heart and the self

The rigidity of the brief balances well with the artists’ individual approaches and interests. Simnikiwe Buhlungu’s Ingubo, Baker’s and Intercape, for instance, brightly evokes the long-distance, cross-country, homeward-bound journeys of the heart that many South Africans know well and have longed for during this time of limited movement.

Right: Autopoiesis (2021). Print by Nonku Phiri.

While Buhlungu considers the communal, Nonku Phiri’s Autopoiesis is conversely a journey into and out of the self, as she reflects on acts of surrender in this seemingly apocalyptic moment. In an interview, Phiri speaks about her movements between lockdowns and her interest in autopoiesis, which is “a system capable of reproducing and maintaining itself by creating its own parts and eventually further components”, such as a biological cell.

An accomplished musician, Phiri describes her drawing as “absent-minded doodling”, the repetitive linework a source of tactile comfort. She explained that in Autopoiesis, the undulating lines reminded her of the waves in abalone shells, a fitting image for the outcome. The comforting print brings to mind the feeling of being encased in a duvet on a rainy day.

A turn to the familiar

Hafiza Asmal’s print, 232.78 degrees, offers an alternate view of comfort by creating visual questions about linguistic ease. She uses South African Sign Language, her home language, to illustrate wholeness and time. Her difficulty in articulating these concepts motivated this turn to the familiar.

The work was inspired by a drawing her nephew made during his stay with her – in particular, the raw innocence in his attempts to illustrate a narrative of our strange reality today. In her artist statement, she describes how the childlike elements found in the image act as a reminder to reflect on how children’s narratives of this pandemic are archives and that “the language of their memory, and their expression, will determine what our reality will mean as a piece of history”.

For co-founder Cordeiro, developing his own narrative and finding a language to process the pandemic demanded emotional heavy lifting. Cordeiro explains that developing his print, The Care Bear Stare, was an opportunity to process his grief after his mother died of cancer in September 2020, as well as the accompanying anger, which multiplied with the reverberating effects of Covid-19.

Right: The Care Bear Stare (2021). Print by Chad Cordeiro.

In this work, he turns to the childhood cartoon Care Bears, a group of multicoloured characters whose ultimate weapon was the “Care Bear stare”. Together, the bears would radiate light from symbols on their stomachs, which combined to form a ray of collective love. This reflection on the complexities of care work for loved ones, especially in this time of great loss, reveals an irrefutable technical competency. An accomplished print technician, Cordeiro has a long history as part of the David Krut Print Workshop, one of the most established print studios in the country.

His contemplations are a reminder of curator Renée Mussai’s concept of curatorial care, the notion that “the exhibition can be a space of refuge, offering both critique and hope”. In this sense, Cordeiro is encouraged by how DGI functions differently to commercial print studios. It does not work on an invitation-only basis; artists can approach the studio directly. The working relationship between the studio and artist is also individually negotiated, with a range of options available for artists to engage creatively, technically and economically with printmakers. In this way, DGI is able to avoid problems of transparency along the printmaking value chain, from production to exhibition and finally to sales.

Militancy and the solitary subject

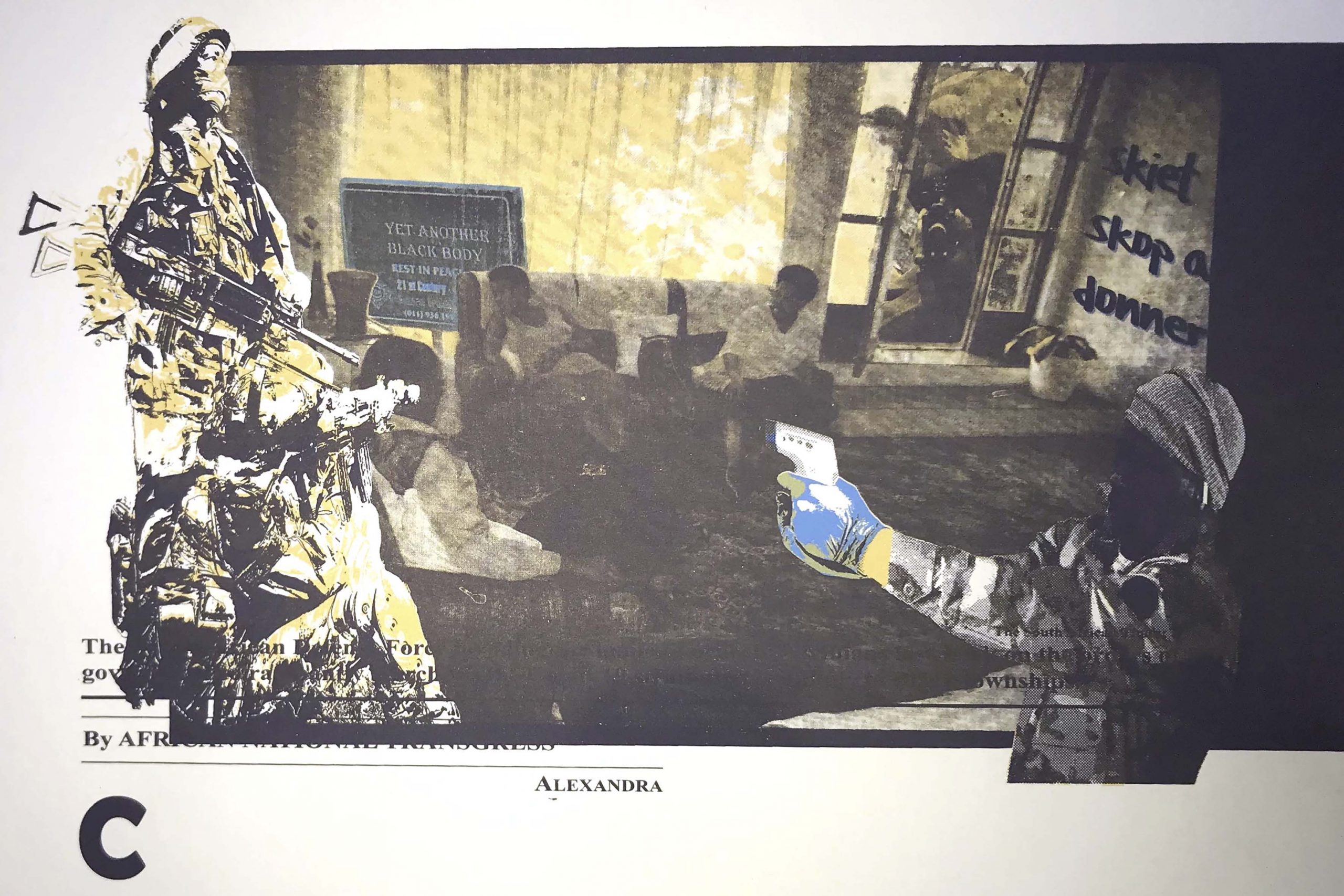

On the far end of the spectrum investigating innocence and care lie sombre meditations on violence and isolation.

For Township Disaster Management Act, Nono Motlhoki took her cue from the emergency regulatory architecture enacted during the initial lockdown in March 2020, when townships were patrolled by the South African National Defence Force, which the public accused of excessive force, physical abuse and brutality. It acted as though it were at war. But at war with whom? This is the question Motlhoki poses in her artist statement, reflecting on the “ill-discipline of the government” as shown by the deadly “extravagance of militancy” displayed in the townships: “The [Defence] Force harassed and murdered people in their display of superiority and power politics. We witnessed a gross mishandling of Black people in the townships – a reminder that our existence in this country continues to be vilified, alienated and then disposed of.”

Right: School for Savages (2021). Print by Nathaniel Sheppard.

Sifiso Temba similarly explores deadly disorder, but where Motlhoki’s attention focuses on institutions, Temba zooms into the individual. Home Alone addresses isolation during the pandemic by looking into lonely holidays. In the work, the solitary subject gazes beyond the frame at a world described in his artist statement as “the chaos and commotion” outside, which refers to the global rules and restrictions, and the accompanying fines governments imposed for deviant behaviour.

Also featuring a solo subject but one that evokes the bustle of the street, Corona Special by Isaac Zavale displays the artist’s visual vocabulary of spaza shop-style signage, using a combination of popping colours in his traditional barbershop poster.

Archival memory

Sheppard explains that his participation in A Labour of Love, a 2017 group exhibition Gabi Ngcobo and Yvette Mutumba conceived and curated, was key to the history of the studio. That exhibition presented 150 works from an archive of 600 original artworks acquired by Hans Blum on behalf of Germany’s Weltkulturen Museum in 1986.

The works, which Black artists produced between the late 1960s and mid 1980s, were a core part of the German museum’s contemporary African art collection and had not been shown in South Africa before 2017. They included Sam Nhlengethwa, David Koloane and Peter Clarke, as well as newer pieces made in response to these works by five University of the Witwatersrand School of Art graduates, including Sheppard and Cordeiro. DGI took up the printmaking baton in an effort to continually reference and reinvigorate archival memory.

This imperative is reflected in Helena Uambembe’s approach to sensitively addressing the erasure of conflicts during South Africa’s wars in Angola and Namibia. In an interview, she explains that she took the photograph that inspired her work Forever Republic of Pomfret in 2018 in Pomfret, a former asbestos mine camp on the edge of the Kalahari, where she grew up.

Right: Home Alone (2021). Print by Sifiso Temba

Pomfret is home to South Africa’s notorious 32 Battalion, a group of mostly Angolan soldiers who fought for apartheid South Africa. The soldiers first fled from the victorious People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola to Namibia (then South West Africa) before the apartheid government recruited them to fight. They were settled in Pomfret with their families in 1989 at the end of the border war, when Namibia gained independence and Pomfret became a South African military base. The base was closed in 2000, leaving the veterans and their families in limbo.

According to Uambembe, the graffito, which reads “Forever Republic of Pomfret”, has been around as long as she can remember, a feature during her holidays there as a child. Today, Pomfret is a ghost town with limited basic services. For Uambembe, this print holds a memorial space for many of those affected by the traumas of war who still consider Pomfret home.

Together with Teresa Fimino, also from Pomfret, Uambembe is a member of the collective Kutala Chopeto, which aims to document and preserve the largely unexplored and painful history of the town. Uambembe’s print is a sombre meditation on the idea of the republic, how it came to be and what its future holds.

State of the nation

My Fellow South Africans by Minenkulu Ngoyi is perhaps the most poignant and prescient in the collection. An image of President Cyril Ramaphosa is worn and weathered, symbolising the strain on the country’s leaders. In the background is a repetition of the Johnson & Johnson logo, hinting at propaganda and mistrust in the availability of the Covid-19 vaccine.

Who will forget anxiously tuning in to hear the president addressing the nation? And how can we allow ourselves to forget the chaos of corruption in acquiring the vaccine? The Roman numeral CXCVI (196) across the president’s mouth represents the number of anagrams that can be generated from the word “pandemic”.

Much like Ngoyi’s poster-like style, which harks back to the importance of printmaking in South Africa’s history of resistance, this visual representation of the diversity of pandemic experiences is expressed and echoed throughout Home for the Holidays.