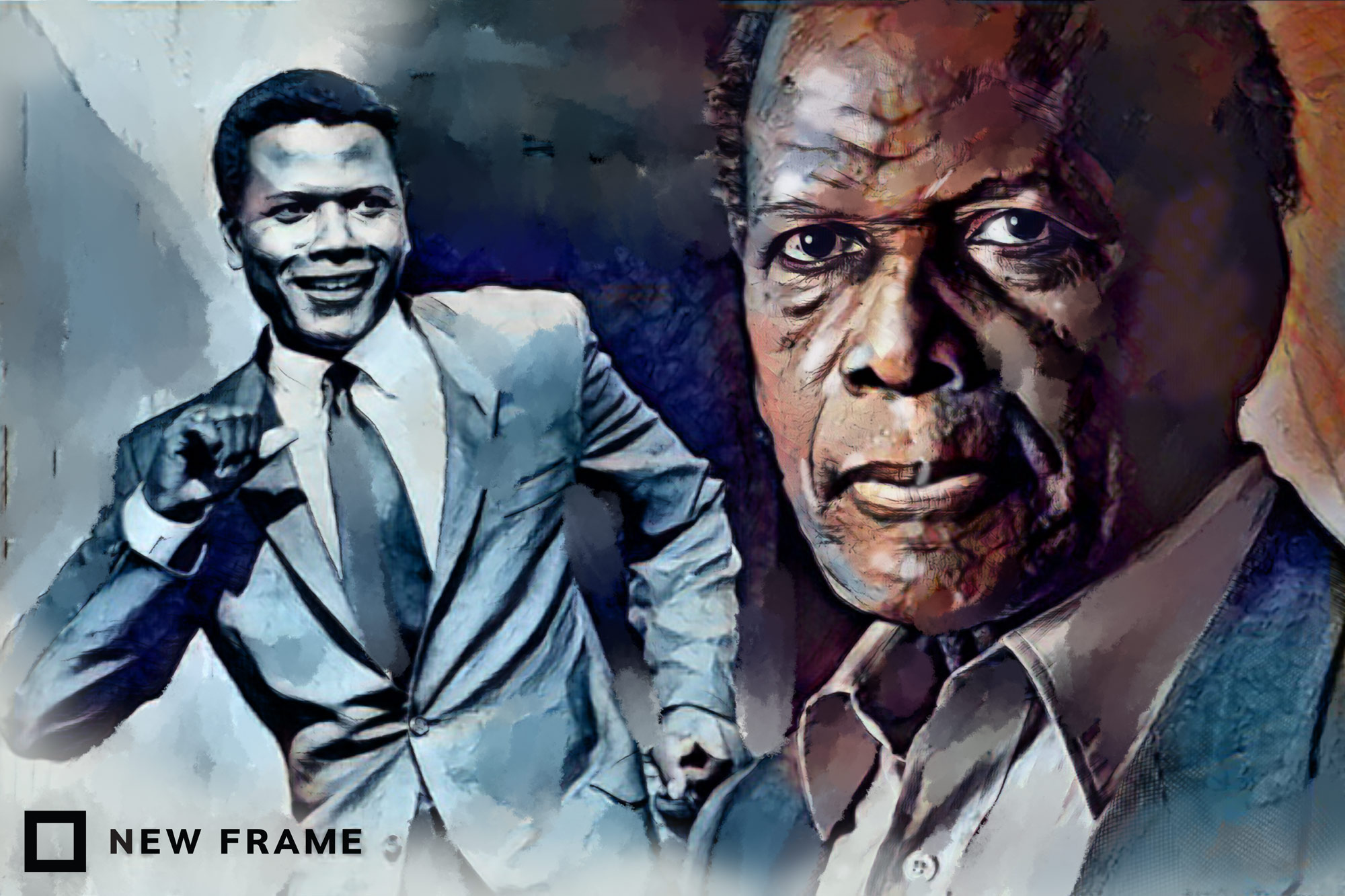

Sidney Poitier, a beautiful dark light

By portraying dignified, powerful Black characters at a time when this was a radical act, the quiet authority of the self-taught actor and activist inspired a generation.

Author:

24 January 2022

Sidney Poitier was born in material poverty, but his life from birth to grave was spiritually rich. Born prematurely on 27 February 1927 in Miami, Florida, he was a frail, underweight infant who the paediatricians were convinced stood no chance of survival. His parents returned to their home, Cat Island, in the Bahamas in preparation for the child’s funeral. The little box that was to be his coffin was prepared, and the family braced themselves for a period of mourning.

The people of the Bahamas and the islands of the Caribbean were more African in their practices during those years. His mother sought an oracle. Unlike the paediatricians, the soothsayer prophesied that the child would not die but would instead walk among kings. That the child’s last breath was taken on 6 January 2022, with eulogies being written across the world, is a celebration of the wisdom of that spiritual woman from nearly a century ago.

The child faced many hardships, but the foundations set from the loving community of Cat Island fortified him along his way. Misfortune led to their migration to Nassau, the big tourist island, and then he went, at the age of 15, to Miami, the place of his birth, which made him a citizen of the United States. He had, by that point, only two years of education. The dire circumstances of his family meant the boy had to work. Indeed, he was, like so many people across the African diaspora and on the African continent, someone whose life consisted of working wherever and whenever he could.

Related article:

In Florida, he discovered one of the great liabilities of being a Black man in the US. He was raised in the Bahamas as a human being with dignity and self-respect. This led to the Ku Klux Klan hunting him for a lynching at the behest of a white woman miffed at his demeanour. He joined the US Army during World War II, where he worked in the medical unit. After his discharge, he moved to New York City – or, more exactly, to Harlem, which, for a good portion of the 20th century, was the centre of the Black world. He worked in menial jobs but, not living with a sense of limits, he auditioned for a role in the American Negro Theatre. His audition failed because his limited education meant he could barely read the script. There was also the problem of his thick Bahamian-Caribbean accent. He was advised to make a living washing dishes.

Ironically, Poitier was thankful for the negative experience. He was determined to prove the casting agent wrong. So, he practised enunciation through listening to the radio, and he worked on his reading skills. By his second audition, the ensemble had moved to a bigger space. Although he failed the second audition, he surmised that the theatre needed custodial services and offered to do the work in exchange for training from the directors, cast, crew and playwrights. The rest is, proverbially, history.

Crossing boundaries

Poitier quickly became a successful actor on stage and screen. What was distinct about him was the dignity and gravitas he brought to his roles. While many Black actors were consigned to subservient roles, his characters crossed those boundaries. His many films are well-known, and the Academy Award he received for best actor in Lilies of the Field (1963) was historic, as he was the first Black male to receive such an award. I should like to add, however, that there are two performances that stood out for me. Both were released in 1967.

The first, To Sir, With Love, is about an engineer who takes a temporary job as a secondary school teacher in East London, in the United Kingdom. It is not only a complex racial portrait, as his students are mostly white, but also has underlying themes of virtue and authority, which Poitier brought to his performance of Mark Thackeray, the schoolteacher. The performance brought to the fore that one could be authoritative without being authoritarian. As the title of the film, based on ER Braithwaite’s 1959 novel, attests, true authority is born of love. That “love” could be used in a context of a Black male character was extraordinary. The underlying message, that hate is withering while love is nurturing, offers an allegory, through the youth, of what could be possible. The film, as I recall, inspired many of us in the 1970s to consider becoming teachers.

I recall, for example, my band’s jazz trombone player, Richard Jackson – a tall, handsome secondary school student – channelling Sidney Poitier in his dress, demeanour and style. Dark-skinned and Jamaican, Richard wore a suit and tie to school, and his hair was always well coiffed. Richard was our Sidney Poitier, and one should bear in mind how significant this was. As blackness received deprecation in the inner cities of the US, to be informed that one resembled Poitier was a compliment. Embodying him was another way of saying “Black is beautiful”.

Related article:

The second film brought another dimension of blackness to the fore. In the Heat Of the Night was about a Black Philadelphia detective, Virgil Tibbs, who gets caught up in a murder investigation in Sparta, Mississippi, after being profiled and arrested by the town’s racist police chief. There are so many powerful moments in that film, but none match the pivotal scene in which a white suspect slaps Tibbs/Poitier. Without hesitation, Tibbs slaps him back and simply straightens his jacket. The catharsis this brought to Black audiences is without saying. One could also imagine the terror it brought to many white ones. At an existential level, there is a deeper consideration: the scene revealed what anti-black racists fear – humanity and dignity in dark skin.

The original screenplay wasn’t written with Tibbs slapping back the suspect. He was supposed to leave the room, flustered. It was Poitier who insisted this made no sense, especially given the character he was portraying – namely, Mister Tibbs. That scene was, then, Poitier’s innovation in a time of Black Power. Those words were much feared even among certain sectors of the civil rights movement. Although power is not solely about force, a crucial element of dignity requires the ability to stand up for oneself, even if one loses. The slapped suspect, Endicott, was shocked that police chief Gillespie didn’t immediately shoot Mr Tibbs, and he subsequently sent a gang of whites to lynch him. The events, in which even the racist Gillespie comes to the side of Mr Tibbs and the mystery is solved, offer another side of the thesis of authoritativeness versus authoritarianism (white supremacy).

Power is revealed in both films through love and courage. As power is the ability to make things happen with access to the conditions of doing so, the love in To Sir, With Love, offers a portrait of the power to empower; the courage in In the Heat Of the Night is the power embodied in commitments to dignity and self-respect. Both converged with what anti-black racist societies hoped to keep at a distance: “Black” and “human”.

Part of the struggle

I won’t here spell out the many accolades Poitier received over the years. I would like to close with a story about him as related to me by his longtime friend Harry Belafonte, another great artist and, I must add, freedom fighter. While Poitier was fighting the symbolic struggle on the screen, he was involved, although without fanfare, in struggles on the ground. He was not only a supporter of the civil rights movement but also the students’ movements. He played his part in contributing funds and other resources, and he even risked his life through personally carrying funds through the US South to activists.

Poitier’s life message was by way of example. He was acutely aware, throughout his life, that he was working for something greater than himself. He earned material wealth, true. He earned fame. But throughout, he was spiritually grounded in what really mattered. There is a saying, mistakenly attributed to Ernest Hemingway, that a great man doesn’t strive to be superior to others but, instead, seeks each day to become better than his former self. Sidney Poitier, the child born with a declaration of death in poverty, became a man whose wealth was greater than the material form. He never took himself too seriously. He focused on what he was to do, and he welcomed, lovingly and openly, others to join him. On screen and off, he managed, despite his quiet demeanour, to say it loud, “I’m Black and I’m proud!” His life was a beautiful, growing flame that lit the wick of so many candles, which means, as his faded away on 6 January, his inspiration continues to shine.