Should learners have to choose between sanitary pads and school?

The National Sanitary Dignity Implementation Framework aims to provide pads free in no-fee schools. Ambitiously, its long-term goal is to distribute to all girls in all schools.

Author:

4 June 2019

“Imagine a learner is not at school for three to five days every month,” says Nomonde Xaba, 55, principal at George Mbilase Primary in Etwatwa East, Daveyton, outside of Benoni. “How many days is a learner missing out on because of a lack of access to pads if you multiply those three days a month for a whole year?”

Xaba’s school has a sanitary bank run by a life skills teacher, Pamela Morope, 58. “When pads are at children’s disposal, this eliminates absenteeism and also contributes positively to their education,” says Xaba. The sanitary bank receives sanitary pads from two private companies that visit the school twice a year.

This year, the school has randomly received three deliveries of 50 sanitary packs from the Gauteng Department of Education (GDE). In each pack, there is a roll of toilet paper, body lotion, roll-on, soap, toothpaste and sanitary pads.

“If it’s Friday, what will the child do when she gets home for the weekend? Is the learner going to wait until Monday? It’s important that the child takes the pack home to have something to use,” says the principal.

Many parents from this community are unemployed. “Children taking the pack home assist parents who would not have been able to afford these items, while other parents can use the little they have for other things like the buying of bread.” The packs are given to learners from grade six, seven and a few from grade five.

But a lack of access to sanitary products is only one part of a much larger problem in a society that stigmatises menstruation. In January this year, Johannesburg mayor Herman Mashaba tweeted that giving girls pads will make them “focus on sex”, “deliberate[ly] destroying the future of our youth”.

Helping learners cope

Martha Sithole, 12, is the only one of the learners that spoke to New Frame who has not started menstruating yet. Like the other girls, she supports educational awareness and the need for free pads. “To me, getting pads for free at school is very important as it assists some learners, who are scared to share with their parents.”

When Zandile Tyiwa, 13, started her period, she told her mother, who had already bought pads in anticipation of her daughter’s first menstrual cycle. “I started having period pains. At first, I was not comfortable. I didn’t know anything, bendibhayiza nje … I thought I was sick or bayangiloya [bewitched],” she says with a laugh. She credits Morope, the life skills teacher, for making her understand her body’s changes.

She was not the only girl confused by her first menstrual cycle. Maria Makopo, 13, started menstruating last year. “I was frightened, thinking I was hurt.”

Thembi Banda, 13, is the only one in the group who had prior knowledge of what would happen to her body when she reached puberty. “I was not alarmed when I started. I told my mother, ‘Look, I am like you now.’” Their relationship prepared her: “My mother and I are close. I always ask my mother, ‘What are you using? That looks like a diaper.’” Thembi is uncomfortable only when her period stains her clothes. This makes her shy away from playing during break time.

Imange Mpukwana, 12, started menstruating this year. The first person she told was her grandmother. “Teachers started giving us pads and these assist a lot of learners who cannot afford to buy them.”

“Giving them all pads lessens shame and offence,” says Morope. “It creates uniformity as they all receive the same thing and all start using pads.”

National roll-out to no-fee schools

The Department of Women (DoW) has developed the National Sanitary Dignity Implementation Framework (SDIF), which provides the minimum norms and standards for the provision of disposable sanitary pads to poor girls and women.

DoW’s Shalen Gajadhar says the initial roll-out of pads is being piloted in no-fee schools. But the longer-term goal is for distribution to all girls in all schools, followed by implementation in public tertiary institutions, then to women in prisons, places of safety and public hospitals, and finally for society as a whole to have access to free sanitary products.

In the 2019/2020 budget, National Treasury made R157 million available to provide free sanitary pads to no-fee schools across the country. The department launched the initiative in Piet Retief, Mpumalanga, in February, followed by a roll-out in the Makana Municipality in the Eastern Cape, in April. In early May, the programme was launched in Durban, KwaZulu-Natal.

During DoW’s recent Menstrual Health Management Indaba, all provinces were invited to discuss “the rollout and to look into variations that may be occurring and how to bridge these to ensure the rollout is standardised across all provinces,” says Gajadhar. Not all provinces were present at the Indaba.

According to the DoW’s media statement, it will take a concerted government effort to implement this programme. Infrastructure enablers like water supply, sanitation, handwashing facilities, the supply of toilet paper and an environmentally safe and hygienic disposal system are all necessary for SDIF to work.

The joint intergovernmental work should result in schools like George Mbilase Primary having access to sanitary bins, so that learners such as Mpukwana can stop having to use communal dustbins for used pads. “After changing, you take the packaging and plastic or toilet paper and wrap it. Then you throw it in the dustbin underneath some rubbish.”

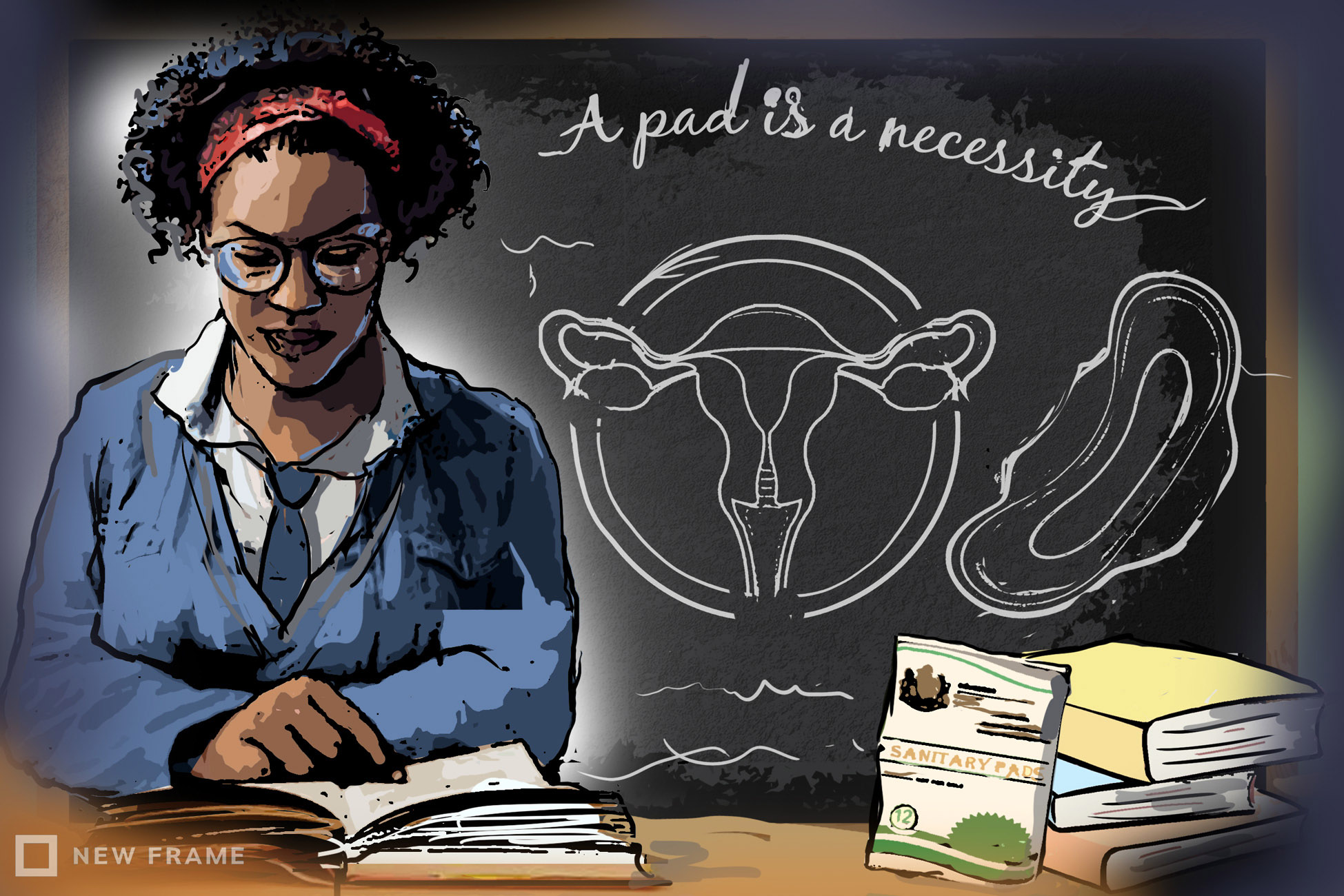

Xaba has compared the importance of pads to school textbooks saying that, like a textbook, “a pad is a necessity”.