Sharp Read | Women in music give voice to history

A few books have fought the erasure of women in music. This Woman’s Work: Essays on Music tries to be one of these, but its inconsistent discourse fails to find a new way to think.

Author:

14 June 2022

If an editor commissioned a bunch of male music journalists, musicians, music scholars and fanboys to create a collection of reflections on music, it would be marketed as simply that: a collection of reflections on music. Its gender composition would not even be noted (except perhaps by those noisy feminists waving placards outside the publishing house). Adding a tiny number of token female names would not alter that.

But if all the writers happened to be women – even if their industry roles, and the scope of their reflections, were near-identical – the marketing would most likely change to showcase the “exceptional” nature of its subject matter: women and music.

Related article:

Yet if music books where female contributions predominate seem exceptional, it is because too often publishers and editors think first of men, whose dominance in the field and its discourses has been naturalised by patriarchy. It is not because expert women don’t exist. Overwhelming evidence demonstrates female participation in music in all roles, on every continent and in every era. But, as with Dr Samuel Johnson infamously observing women preachers, many publishers and editors remain “surprised to find it done at all” – and it shows in their marketing.

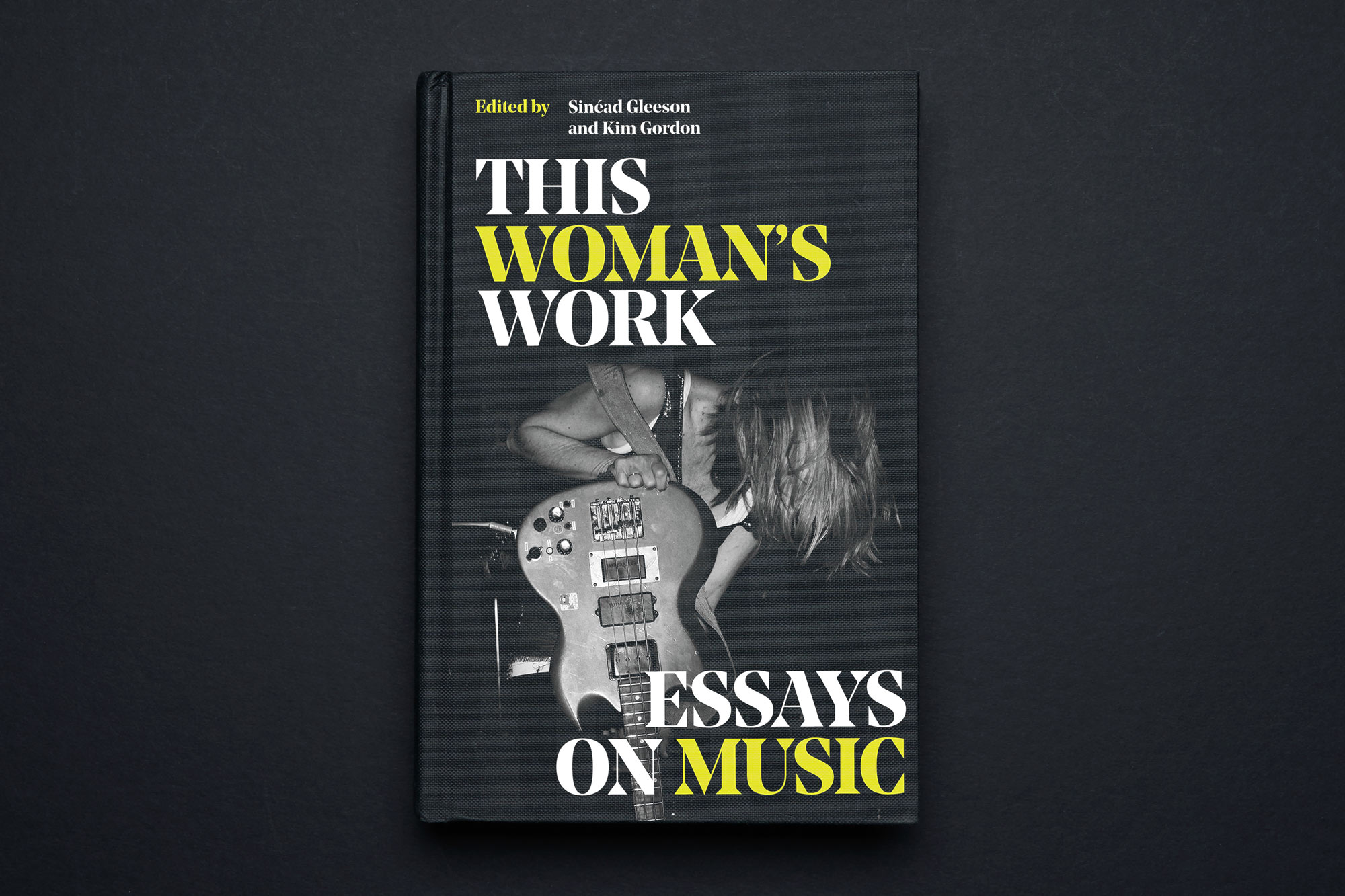

Female-helmed books such as Sinead Gleeson and Kim Gordon’s This Woman’s Work: Essays on Music (White Rabbit, 2022), published in March, provide a vital expressive space for previously excluded experiences and discourse. The book’s back cover blurb makes larger claims: that it “[offers] a new way of thinking about the vast spectrum of women in music”.

Cover blurbs are marketing, not critical commentary. But it is perhaps worth considering that claim, and the role such publications have in challenging the current patriarchal music landscape and shaping a new one where roles, expression and aesthetics are not deterministically shackled to gender or sex.

Human voices

There is now significant and growing scholarly work on women in music: revisionist works of history and musicology that reveal female participation and leadership in multiple music contexts and genres where women were assumed to be minor or absent, and rich theoretical explorations of gender and musical identity. Such work has laid robust foundations for further study. Biographies and autobiographies of female performers and other role players also proliferate, and since at least the 1990s, even mainstream media have found space for journalism – often from women – about women musicians. This Woman’s Work reflects some of these approaches, but what it actually does – assembling diverse reflections about making, facilitating and experiencing (mainly Western, popular) music – is nothing like as novel as its marketers claim.

It’s instructive to read the book against two other, analogous volumes: Sarah Cooper’s collection Girls!Girls!Girls!: Essays on Women and Music (NYU Press, 1996), and Renate da Rin and William Parker’s Giving Birth to Sound: Women in Creative Music (Buddy’s Knife, 2015). That time span lets us explore changes in contexts and experiences as well as in how these are written about. Together, the three books help map change – and the journey that remains.

Girls! Girls! Girls! (the title is ironic) reminds us how long ago, in terms of social change, the 1990s really are. This is a world of physical music consumables: LPs, cassettes, hardcopy magazines, physical record stores. Women are present in music but, in many contexts, only beginning to assert their visibility. That predigital music technology had its own processes and enforcers of gender gatekeeping – “my two older brothers decided what records we played” notes journalist Rosa Ainley. From the perspective of 2022, that provokes all kinds of questions about if and how the dominance of digital distribution and consumption has changed things.

Subject matter ranges across genres, including rap, bhangra and classical music, for which last musicologist Sophie Fuller provides a concise, comprehensive history of female exclusion. The book is largely unburdened by academic jargon (the construct of “intersectionality” had been coined only seven years previously) but in subject matter, endnotes and allusions, a clear awareness emerges of how race, class, gender and power intertwine and overdetermine one another. One striking example is photographer and music journalist Val Wilmer’s essay Tell the Truth: Meeting Margie Hendricks, about a vocalist sometimes dismissed as merely Ray Charles’ backing singer and the impact of “her attitude and refusal to conform”. Another is Helen Kolawole’s exploration of how women negotiate between their love of the sound of rap and what is often their revulsion at the lyrics. Kolawole does not speculate: she asks and listens.

The writing is not always literary; it is more often journalistic and sometimes conversational and slightly rough around the edges. The collection is all the stronger for that: these are highly personal reminiscences and reflections, and the book is crammed with human voices, human interactions and wry, sparky wit. Cooper’s introduction clearly contextualises her choices and there’s a useful index of proper names. There is no lexical drift here: this is explicitly a book about women “and” music that includes a few women “in” music. Not counting the women music-makers (mainly DJs) whom Kolawole interviews, only one of the 12 authors describes herself as a working musician; most are journalists.

Placeholders

“And music”/“in music” is one of the contradictions This Woman’s Work does not acknowledge or resolve, possibly because its foreword makes no attempt to contextualise the contribution choices that follow. Songwriter Heather Leigh simply provides some descriptions of contents, and her accompanying personal reflections would have fitted as well into the book’s body. There is no index, which is revealing about how editors envisage the book being used. Leigh is one of only four out of 17 contributors who are described as musicians; two of those inhabit the same chapter. Not surprisingly, that conversation between editor Gordon and Japanese performer Yoshimi Yokota is one of the most illuminating in the book. Called Music on the Internet has no Context, it is also one of only two chapters in the 2022 volume to address directly the materialities of the difference digital has made to women’s work in music. The other is a profile of electronic composer Wendy Carlos.

This Woman’s Work is a far more eclectic selection than Girls! It contains some illuminating accounts of previously hidden history, particularly Liz Pelly’s excavation of the work of Agnes “Sis” Cunningham, who played a pivotal role in the radical folk music movement of America’s 1930s and 1940s, often stereotypically associated with male singers such as Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger.

Another word that has popped up in the book’s marketing is “stellar”, because chapters have been contributed by well-known fiction writers such as Fatima Bhutto, Anne Enright, Rachel Kushner, Yiyun Li and Ottessa Moshfegh. Those certainly provide writing to savour, and in Enright’s case, the wittiest piece of prose in the book, on her shifting relationship as a fan with multifaceted musician Laurie Anderson. Moshfegh illuminates the issue of women and creativity, but although music is the cue, what we really learn about is her becoming a writer. And sometimes the observations of such outsiders to the making of music are too broad to illuminate anything, such as Bhutto’s “musicians helped end apartheid by boycotting…”.

Related article:

Indeed, too many of the essays in This Woman’s Work deal with music as what Li calls “placeholders for life”. That only works if both the life and the writing are interesting enough, and although Bhutto’s is, the same cannot be said of some others. One chapter is simply a dreary litany of “this is the music I was listening to when I was sleeping with…”. When early feminists began asserting (correctly) that “the personal is political”, they did not mean that the solipsistic is.

It would do This Woman’s Work an injustice not to note the chapters that transcend the “placeholder” approach. As well as Gordon and Pelly, poet Margo Jefferson inscribes the embodiment of jazz and life as a Black woman as she writes of Ella Fitzgerald, who “laboured to be beautiful”. Zakia Sewell raises the ghost of colonialism and slavery and spins the bonds between mothers and daughters as she hears old tapes of her mother’s songs. Kushner’s account of the life of Wanda Jackson dissects the tensions and overlays of race, class and gender in Jackson’s career and their differently nuanced intersections in country, gospel, rock and rockabilly music, with their pervasive and often deliberate blindness to Black antecedents.

Most powerfully, Juliana Huxtable’s essay on the names missing from male critics’ 1970s canon of jazz innovators – Abbey Lincoln, Jeanne Lee and most notably Linda Sharrock – brings together the theory and the human meaning of “extreme noise” for oppressed and resisting lives. Who Huxtable, born intersex and initially assigned male, was sleeping with when Sharrock sang is relevant here: living fully as a woman was part of the same gender resistance. “In the canonisation of jazz, particularly what is understood as free jazz,” Huxtable writes, “the sonic innovation of vocalists, especially women, is always a secondary consideration to the appraisal of musicality.”

The music that matters

It is ironic that the titles of This Woman’s Work and Giving Birth to Sound share a thematic thread. The first alludes to the Kate Bush song imagining a male reaction to a woman’s difficult childbirth. But that title is just a tag. Nowhere is its choice for this book explained or linked to the contents. Given that music as work is another area currently preoccupying scholars, it might have been employed as a thematic tie – but it isn’t. By contrast, Giving Birth to Sound – a collection of 48 essays by women who write or play music, mainly in the context of jazz and other improvised forms – is explained, problematised and discussed explicitly on the opening pages before being accepted. As one contributor objects, “Would you ever see a book entitled Sperm Donors’ Seeding of Sound: The World of Men Musicians?” But as another responds, “Taking the titling on as a group [is] a very woman’s way to do this.”

Giving Birth to Sound speaks exclusively for women “in” music, not women “and” the art form. Contributors were given 20 questions upfronting gender identity in musical creativity to shape their entries, although not all responded to everything asked. This by no means created uniformity. Vocalist Jen Shyu provides a Timorese parable; flautist Nicole Mitchell shapes her response around an extended, poetic trip through Black history and lives, including her own, speculative fiction writer Octavia Butler, jazzman Sun Ra and godfather of soul James Brown. Ijeoma Chinue Thomas simply writes a poem. While for South African singer Yvonne Chaka Chaka in the pop ditty a DJ may have saved her life, for violinist Rosi Hertlein in this book it was Thelonius Monk. Bassoonist Karen Borca subverts the assumption – actually expressed by rock critic Caroline Sullivan in Girls! – that women may be less geeky about music than men, with her detailed exposition of the complexities of trimming a bassoon reed.

What emerges is that for women in music as for men, it is the music that matters. The gender assumptions and stereotypes of society affect the contexts and constraints within which that music is made and influence what it says, but they don’t change the central truths: sound matters. Women in music are first and foremost shapers of sound. Some women have chosen not to have children to be freer to make music; others are mothers who have learned, like Mala Waldron, to “make it clear that your art is not an option”. Too many, across countries in Asia, Africa, America and Europe, continue to be insulted by the same “compliment”: “You play like a man.”

The contributors do see differences in socialisation that emerge in the music made by women and men. Men are socialised towards hierarchical structures, fragmented roles, “loud, fast playing, major scales, even meters … and written scores”. More women find it easier to embrace the yin fluidity of egalitarian structures, spontaneity and orientation towards process rather than product. But repeatedly contributors assert that all genders have the capacity for both these approaches, and that what is needed is a demolition of the boundaries and a search for balance. For singer Maggie Nicholls, making music is “practising a better society”.

In the end, and despite some superb individual essays, This Woman’s Work is fatally undermined by its lack of consistent discourse. Chapters sometimes cite their sources; the book as a whole does not. And not acknowledging the body of work that preceded it is more than mere omission. It robs the contributions of important situating context for readers, and it disrespects those women’s work that went ahead. “Citation is feminist memory,” feminist scholar Sara Ahmed has admonished.

When asked about the role of Black writers in science fiction, Butler responded drily, “We’re here.” Books such as This Woman’s Work do fulfil a purpose by making that same assertion around women and music. That this remains necessary tells us how far gender struggles still have to go. As Ahmed has also observed, it is not yet “the time to be over it, because it is not over”.

But Butler also observed: “I write to create myself.” Realising revolutionary (in all senses) creative identities is what really matters about women in music: the aspect whose exploration genuinely foregrounds “a new way of thinking.” Readers looking for that would be better advised to acquire a copy of Giving Birth to Sound.