Sharp Read | Violence and the Female Fear Factory

By manufacturing fear, patriarchal society contains, confines and subdues women, who are conditioned from early on to tolerate abuse, Pumla Dineo Gqola argues in her new book.

Author:

17 August 2021

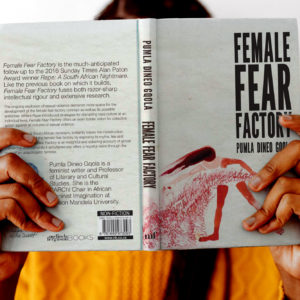

Pumla Dineo Gqola’s new book Female Fear Factory expands on a concept she coined in her award-winning Rape: A South African Nightmare. When Rape was released in 2015, I was an honours student at the university known as Rhodes in Makhanda. Within a year of its launch, I was in the midst of the #FeesMustFall and #RhodesMustFall movements as well as anti-rape protests on my campus. For the rest of that year I consulted the book closely as I tried to make sense of the collision of the anti-rape and anticolonialism movements around me. Its companionship served me well for the years that followed.

Rape laid the groundwork not only for Gqola’s new release, but also for much of the scholarship and thought on gendered violence that has emerged in South Africa in the past few years. The predecessor to Female Fear Factory distilled the interconnected histories of racial discrimination and sexual violence for me and now forms part of the foundation of my research as a feminist sexual violence scholar.

Fear factory

Gqola describes the Female Fear Factory as “a performance of patriarchal policing of and violence towards women and others cast female, who are therefore considered safe to violate”. Those subject to it are trained to fear for their safety and to take steps to protect themselves. But this is a fruitless form of protection based only on the adherence to gender norms. When these norms are transgressed, social punishments – such as shaming – and physical violence ensue. As such, the Female Fear Factory relies on performance. As she explains, the violence that upholds it must be showcased publicly, which not only affects the victim but also instils fear in any witnesses.

For Gqola, the “female” in Female Fear Factory refers to a process of subjugation based on binary gender norms rather than on biology. As she explains, the Female Fear Factory applies to all women, but also to people of other genders. “Women are not automatically female but are made so, in a process that leads to different genders being made female.”

Read an excerpt:

The importance of the Female Fear Factory, both the concept and the book, is that it crystallises a reality with which many are familiar, but which lacked a clear and precise description. The Female Fear Factory is experienced every day, all the time. Its essence is captured in Koleka Putuma’s poem, Memoirs of A Slave & Queer Person from her collection Collective Amnesia, which reads:

I don’t want to die with my

hands up

or

legs open.

Gqola starts off Female Fear Factory by explaining the concept and diving into its components, explaining that she uses the term “factory” because this fear is “manufactured”. She then goes through the fictions that uphold the Female Fear Factory and lays bare the myriad ways it plays out by citing examples taken from countries spanning five continents.

Rethinking xenophobia

In the chapter Foreign Familiars, Gqola shows how xenophobic violence in South Africa is not fully understood. The violence, she contends, is often reduced to criminality or ignorance about the role other African countries played in South Africa’s anti-apartheid struggle. But Gqola argues that this violence is predicated on intimacy and proximity rather than on the disconnection presumed to characterise dynamics between “citizen” and “foreigner”.

Drawing on Xoliswa Sithole’s documentary Martine and Thandeka, which is set during an eruption of xenophobic violence in 2008, Gqola uses the testimonies of the two women after whom the film is named to reveal a cross-section of the violence they face. This selection reframes our idea of who becomes a victim of this form of violence by disrupting the image within the public imagination of men attacking other men during xenophobic violence. Gqola also reads the women’s vulnerability as inseparable from their political identities as impoverished, migrant, Black women. In doing this, Gqola builds on the work of several scholars who have studied how citizenship and the state are formed, adding that the violence of nationalism, like other forms, plays out in the sphere of intimacy.

Related article:

While reading Female Fear Factory, I resonated with Gqola’s line of thinking that positions foreignness as something “made”, rather than a static trait. While having lived in South Africa as a non-citizen for several years has made me familiar with the formal processes of migration, I have found that other people’s perceptions of me as a “foreigner” can be fluid, dependent on where I am, the languages I speak, my accent and an assemblage of other markers that feed into how foreignness is imagined to look.

In Foreign Familiars, Gqola’s analysis of xenophobic violence reveals the depth of the contradictions between citizenship status and vulnerability, as she explains that “the ‘foreigners’ prone to physical attack are very specifically located”. I was reminded of Tariro Ndoro’s poem Black Easter (Reflections) from her collection Agringada: Like a Gringa, Like a Foreigner, in which she addresses how xenophobic violence is sometimes minimised.

“How bad can it be, really?

my cousin Farai made it his mission

to be the hardest thug on the street

so his neighbours wouldn’t target him

How did that work out?

it didn’t.”

Related article:

Like Ndoro, what Gqola pinpoints in her work is how quickly one can go from being a neighbour to being rendered a “foreigner”. She also notes that the vulnerability to such violence is only applicable to people who do not carry certain privileges. Those, she writes, who are white, live in middle-class and affluent areas and/or hold North American or European passports are not subject to the treatment meted out against “African immigrants living among poor Black people”.

Crucial to the point Gqola is making here is the impact of proximity. As she writes, referencing Martine and Thandeka’s narratives, “It becomes clear that those who displaced them had specific knowledge about these women’s citizenship. It is intimate knowledge that created risk and enabled both women to be remade as ‘foreigner’ again and again.”

Gqola’s argument that foreignness is continuously and selectively made rather than being linked to citizenship parallels her conceptualisation of a “female” in the Female Fear Factory. “Female” and “foreigner” are significant not for who they are commonly understood to be, but for how they are produced, made and remade in an effort to reproduce the subjugation of particular bodies.

The dangers of intimacy

During the virtual launch of her book, Gqola spoke about the role of intimacy in the Female Fear Factory: “Intimacy is not a level playing field … We don’t think enough – outside feminist thinking – about how intimacy is a minefield of things.” Intimacy in itself does not, she added, collapse the power disparities between people in a relationship. She also observed how the myth of “stranger danger” persists, despite feminists illustrating how intimate spaces and relations – the home, the family and romantic relationships – are in fact the primary sites of violence.

In one of the most insightful threads in the book, Gqola unearths the ways in which beliefs about romantic love are implicated in maintaining the Female Fear Factory and in furthering oppression. She argues that such beliefs uphold the myth that rapists and other abusers are strangers, when more often than not, intimate partners perpetrate such violence. Over several chapters, she weaves together a picture of how intimacy and violence are interlinked. We are conditioned, she writes, from early on to desire and participate in “patriarchal romance”. Women are taught to “desire domination” in which violence in relationships is distorted as “energising passion”. Gqola then charges patriarchal society with idealising and normalising abuse in heterosexual relationships, wherein it is portrayed as “commitment, real love or ‘going through a rough patch’”.

To keep themselves safe, women are expected to live by a set of rules. But Gqola’s insight makes it clear these rules don’t work. One of them is that as soon as violent men make us uncomfortable or abuse us, we must leave. Such a rule simplifies the context within which we live by failing to acknowledge how, because of the conditioning that sometimes renders romance indistinguishable from domination, abuse is not “always immediately recognised as such”. As women focus on changing their behaviour in pursuit of safety, the Female Fear Factory is upheld and continues to “exhaust and kill us”.

Related article:

Gqola’s focus on intimacy and power also speaks to my own research on consent and sexual violence. In Rape, she writes that the threat of rape is “an effective way to remind women that they are not safe” and “leads to women curtailing their movement in a physical and psychological manner”. When I conducted my master’s research on sexual consent in 2017, I wanted to examine these constraints to understand how they affect Black women’s sexual, intimate relationships.

One of the insights I remember from my fieldwork interviews came from speaking to a woman about unwanted sex. She told me about a situation in which she had consented to having sex with a man not because she wanted to but because she thought refusing might compromise her ability to get home safely. When I asked her – although I already knew – what she was afraid would happen if she refused, she recounted stories of friends who had been chased or left in precarious situations by men with whom they had refused to have sex. So, on that particular night, having been mugged a few weeks prior, she did not want to walk home alone at night. As we both knew, because of what Gqola describes as our “fluency” in the Female Fear Factory, her options were limited by the ever-looming threat of harm.

As we continued our conversation, we also spoke about romantic relationships and what consent looked like within them. She spoke to me about how being in a romantic relationship came with spoken and unspoken pressures to have sex with one’s partner. Of her own relationship, she spoke of the “burden” of this, which was tied to a fear of losing the relationship or being cheated on. Even when it is not centred on physical harm, fear can govern our intimate lives.

Related article:

The interviews I conducted as part of my research affirmed my intuition about the promotion of sexual consent within anti-rape advocacy. As an activist, sexual consent was the go-to response to fighting sexual violence. But my experiences began to show that it was not the panacea it was made out to be. Through my research, I was able to articulate why: the framing of sexual consent tended to reduce the complexity of intimacy to a matter of being able to say “yes” or “no” to sex. But this did not take into account the power inequalities in the environment in which these decisions were made.

Gqola’s argument about inequality within intimacy shows, as I found, that the popular framing of sexual consent was inadequate as long as it did not take into account structural factors such as the economic marginalisation of women or social incentives, including the affirmation of one’s womanhood through securing romantic love. In Female Fear Factory, intimacy is a stage upon which contestations of power play out.

On masculinity

In Female Fear Factory, Gqola disputes the claim that the type of toxic masculinity displayed in xenophobic violence in South Africa is the opposite of “celebrated postapartheid masculinities”. Rather, she argues that such masculinities are the apex of aspirational nationalism, forming what she calls “aspirational masculinity”. In the postapartheid nation, the aspirational subject is a corporate figure “who sees Africa as an untapped market ready for his development, mining and exploration”. This aspirational masculinity feeds into the larger trend of South Africa positioning itself as “exceptional” and superior to the rest of the continent. The masculinism of xenophobic violence is not an anomaly. Rather, Gqola argues that “the young violent men who are the face of xenophobic South Africa are performing with their bodies what South African business and the South African state routinely performs through money and visa requirements”.

This line of thought is reminiscent of another of Gqola’s arguments. In Rape, she made clear the link between the history of colonialism and apartheid and the phenomenon of rape in the present. She references Ania Loomba’s research, explaining how European colonialism replicated itself through rape. Loomba writes, “The coloniser was represented as rapist and the ‘discovered/conquered’ land as a naked woman.” Gqola adds that, through this, “we see that the empire imagines itself as rapist of land and people”. The parallel here is between how South African corporate capital frames the rest of the continent and how perpetrators of physical xenophobic violence imagine those they render foreign. In this way, Gqola’s body of work captures how the logic of colonialism makes itself manifest through patriarchy, capitalism and xenophobia. In each case, the dominant party construes the oppressed party as inferior and then enacts violence against the latter to maintain domination.

Masculinities scholar Gcobani Qambela’s recent research also teases out specific masculinities in South Africa. Drawing on his case study of Peddie, a small town in the Eastern Cape, Qambela writes back to conceptions of Xhosa masculinity that figure initiation as the primary route to affirming one’s manhood. Instead, taking into consideration unemployment and other socioeconomic problems facing men in Peddie, Qambela shows that men who had not undergone initiation could obtain social status through their economic class “in ways that sometimes superseded men who had undergone initiation”. The value of dynamic approaches to understanding gender, which conceive of masculinities as fluid and heterogeneous, is reiterated in this rich analysis.

Related article:

Qambela and Gqola’s work both demonstrate that while toxic masculinities are understood to be at the root of patriarchal violence, to understand its complex workings, we have to critique how gender and other axes of power such as class and nationality operate and shift. Such an analysis can still highlight the specific forms of masculinity that contribute to gendered violence. In Female Fear Factory, Gqola references a campaign in India that carried the message “Protect your daughter” as a response to gender-based violence. Gqola criticises this kind of message as “legitimising a protectionist, infantilising masculinity”, which echoes responses to advocacy against gender-based violence that appeals to men by urging them to protect “their” women. Messages like these, Gqola notes, only reinforce the Female Fear Factory as they fail to address violence at its source.

A seasoned cultural critic, Gqola honours multiple mediums of knowledge in Female Fear Factory, drawing from documentaries, fiction, media reports, essays and academic texts. In the preface and at the end of the book, where she is more reflective than in other parts, Gqola is optimistic about the possibilities of unmaking patriarchy’s brutality and “refusing the prison of fear”.

Throughout the book, she carries feminist hope and remains instructive about the need to explode the mechanisms of female fear. In this she is unshakeable, and through Gqola’s personal reflections on the Female Fear Factory, the reader sees its roots in her decades of anti-rape advocacy work.

Overall, Female Fear Factory is able to stand on its own merit. What Gqola is able to achieve with it is a demonstration of the nature of patriarchal violence and some of its ramifications. The result is an invitation for engagement. Female Fear Factory has plenty for others to build on and reconceptualise, the fruits of which I look forward to seeing in the years to come.

Female Fear Factory is published by Melinda Ferguson Books.