Sharp Read | The road to rugby glory

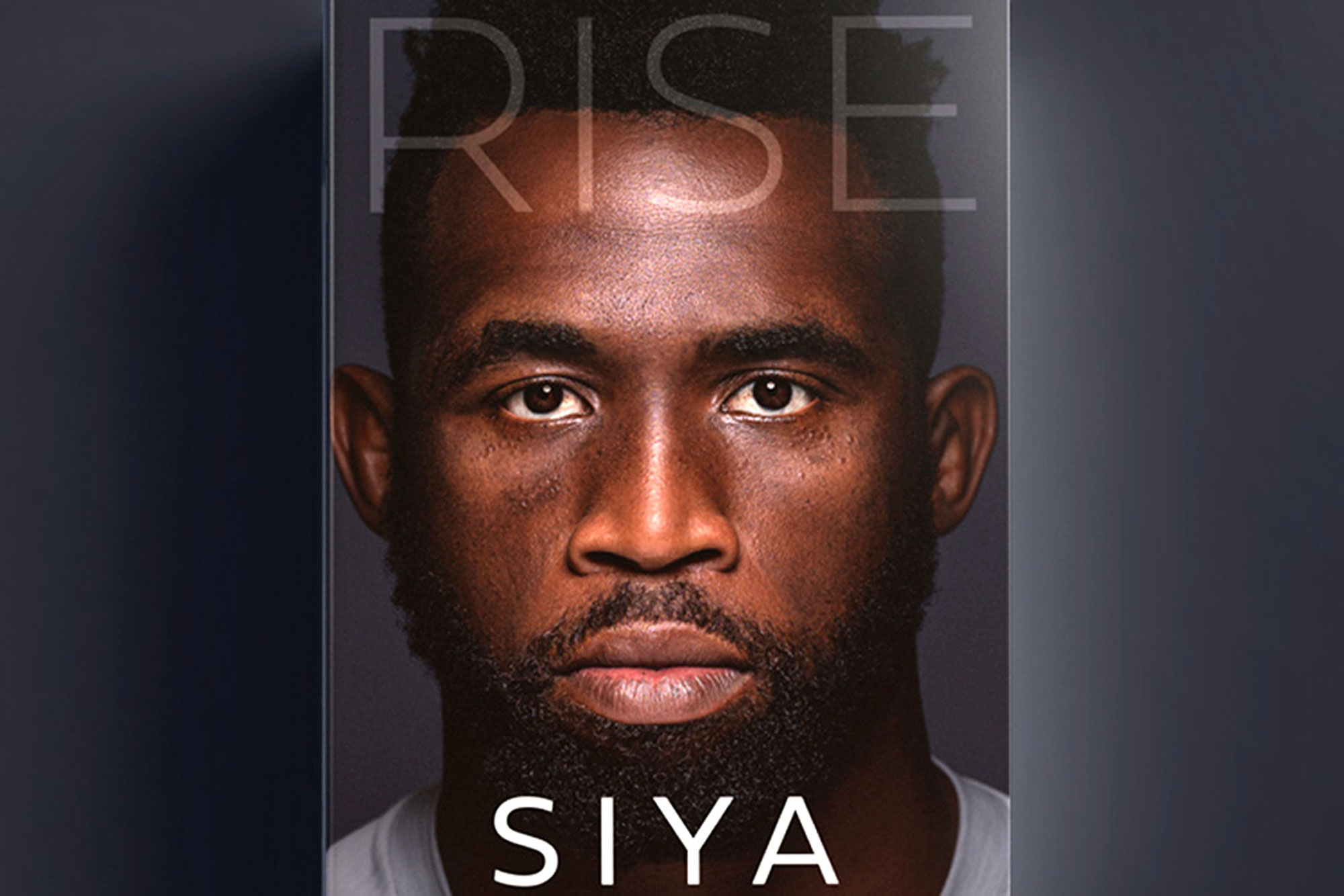

Rise tells the enthralling story of how Siya Kolisi came to be the first Black captain of the Springboks, but it fails to fully reveal the humble, humorous man behind the symbol.

Author:

28 December 2021

Siya Kolisi stopped being just a rugby player on 28 May 2018. He transformed into a symbol of hope for many that Monday, when he became the first Black captain of the Springboks, a team that proudly wears the last socially accepted symbol of apartheid.

“It was indeed a massive thing,” Kolisi says in his autobiography Rise (HarperCollins, 2021), ghostwritten by English writer Boris Starling. “My appointment meant so much to so many people. To them, I wasn’t just a rugby player, let alone a skipper, I was a symbol, a totem, a talisman, and with that came an awesome responsibility not to let them down.”

That responsibility also came with a massive burden. The apartheid hangover that lingers over the Springboks goes beyond the team still sporting what was a symbol of white supremacy. There are still racist elements in the sport and those elements labelled coach Rassie Erasmus’ decision to name Kolisi captain a political appointment.

Related article:

Because of such thinking, Kolisi’s success or failure wasn’t going to affect him alone. This is the heavy toll Black people who break any white ceiling have to pay. If he did well, his success would open doors for more Black players to be trusted with leadership positions at the highest level. If he failed, it would firmly shut a door that had barely opened when he stepped up to lead the Boks.

Kolisi was diplomatic when asked if he thought he was a political appointment, famously saying he is there to inspire not only Black people but every South African, regardless of their skin colour. But he knew the significance of his appointment. “It wasn’t just the destination that was important, but the journey too,” he says in the book.

“Being the first Black captain was made immeasurably more meaningful by the journey I’d taken to get there, because that journey was one which had been denied to thousands of talented players before me purely because of the colour of their skin.”

Walk in his shoes

That journey began in Zwide, a township in Gqeberha in the Eastern Cape. That’s where Rise begins, on 16 June 1991 when Phakama (Kolisi’s mother) and Fezakele (his father) welcomed a baby boy while still in their teens. Kolisi lays bare the type of environment he grew up in, from the violence to the crime, the poverty and the hunger he endured.

“Hunger is not just being hungry, the brief sensation of discomfort which lasts only a few hours until the next meal. Being hungry is easy and commonplace. Hunger is different. It’s all-consuming. It was all I could feel and all I could think about,” Kolisi says in a candid moment in which he not only describes his upbringing but takes off his shoes to allow the reader to momentarily walk in them, to appreciate what it took for him to become a world champion and the first Black captain to lift the Webb Ellis Cup.

Related article:

To achieve that, Kolisi had to rise above the challenges he faced from birth as well as personal demons, from alcohol abuse to reckless behaviour that threatened to end his rugby career before it had even begun. “I was a bad drunk – not violent, but prone to getting so wasted that I’d pass out in the street. I’d get arrested and then wake up in a police cell with no idea how I’d got there or even which police station I was in. I had too much fame and money before I had the character to handle them.”

Most autobiographies tend to paint the subject as a saint, magnifying their triumphs while hiding their shortcomings. Kolisi lays most of it bare, and if the book had been written by a writer who understood Kolisi’s environment and the man himself, it would have been even more powerful.

A funny guy

Starling has an impressive résumé as a writer. He has ghostwritten the autobiographies of former Wales captain Sam Warburton and renowned jockey Frankie Dettori, so is a wordsmith experienced at being invisible. But he fails the reader in Rise by not seeming to fully understand his subject.

He intrudes at times with turns of phrase and language that Kolisi doesn’t use. And Rise falls face first into the trap of writers and pundits from Europe centring the success stories of players from the Global South on overcoming poverty. In this way, Starling portrays the Bok captain in a one-dimensional manner rather than offering a profile with more depth.

Kolisi’s story is much more than a tough upbringing and resilience. He has a credible work ethic, and he is funny and entertaining. But you see this humorous side only once in the book, when he tells the story of watching his beloved Liverpool play football while sitting with Chelsea supporters at Stamford Bridge. His antics led to teammate Eben Etzebeth promising to “klap” him, and afterwards he tells how he reacted to being mistaken for Ivorian forward Wilfried Bony, who was on the books of Manchester City at the time.

Related article:

On the back cover, it says “Rise is not simply a chronology of matches played and games won”. But for the most part, it is exactly that. Half of the book is essentially Kolisi relaying a highlights reel of his career. But those who have followed Kolisi’s career closely know what happened in those matches, and those who care about the games can look them up. It would have been more rewarding if Kolisi had taken readers into the changing room and into his head, revealing what he was thinking and what drove him during those games. You get crumbs of that, but most of the book is dedicated to a play-by-play of points scored.

The book does deliver though on its promise of being “an exploration of a man’s race and his faith, a testament to attaining a positive mindset and a moving reminder that it is possible to defy the odds”.

The struggle for balance

This is brilliantly captured in Kolisi’s anguish of belonging. He finds himself torn between his “old” life in Zwide and “new” life at Grey Junior School after he receives a bursary to study at the prestigious school. Though only a 15-minute drive separates the school from where he was born, the two places are in different worlds. “Being a Grey boy wouldn’t mean I was no longer a Zwide boy, not if I could help it,” Kolisi says in the book.

“I wouldn’t prioritise one identity over the other: I’d make sure they’d live alongside each other, equal and indivisible, points on the same spectrum. We are all nothing without our past: it’s what helps us make sense of our present and future.”

This duality is something with which Kolisi still struggles. He is both an outsider and part of the rugby establishment, coming from an impoverished township where captaining the Boks was the furthest thing from his mind but also an alumni of Grey, one of the elite schools that for a long time was one of the few from which Springboks came.

Related article:

You see that struggle to find balance between where he comes from and where he is now when he discusses the Bomb Squad incident. A racism storm erupted when a video of Makazole Mapimpi being waved away by Francois Steyn, who then went into a huddle with only white players, surfaced after their win over Italy in the World Cup.

Kolisi starts by admitting he “could see why the spectre of racism raised its head; this was South Africa, after all, and there had been plenty of times in the past when the squad had suffered serious racial tensions.” But in the same breath he fails to understand why few gave the Boks the benefit of the doubt. This is a man who is part of the establishment talking, and his statement could be seen as diminishing the hurt of “outsiders”. As a symbol, Kolisi is bridging the gap, if not with words then by what he stands for. That was seen with the Gwijo Squad confidently finding its voice in rugby stands, a place where some of their members were told that they were in the wrong place as football wasn’t playing there.

Rise is broken down into seven chapters – “Schoolboy”, “Stormer”, “Springbok”, “Skipper”, “Summit”, “Society” and “Solidarity” – before ending with a personal statement of Kolisi’s core values, along with his mission for the coming five to seven years and how he plans to achieve it.

Overcoming the albatross

With the life Kolisi has lived, only a fool would bet against him realising the grand ambitions he has set himself. They go beyond personal glory and are goals to create a better society, to ensure other children don’t face the hardships he endured.

“In a sense, I’m tired of being celebrated because I suffered and still managed to make it … Be inspired by those who defy the odds, sure, but also be angered and appalled by the fact that they had to face such odds in the first place,” says Kolisi.

Even with all his success, the burden of being the first Black Springbok captain remains. In fact, his success has become an albatross. Kolisi has to put in superhuman performances to be acknowledged as a vital cog in the Bok machinery.

Related article:

That’s what has fired him into a storming 2021, making the World Rugby Dream Team of the Year even though the Springboks spent much of the year inactive because of Covid-19. When they eventually competed, they were undercooked and had no place to hide against some of the toughest rugby sides, including the British and Irish Lions. South Africa handled themselves well, winning eight of their 13 Tests, including two against the Lions to win that series. But Kolisi wasn’t happy with their overall performance this year. Still, even in the face of defeat, he had the right words to say after an emotional week leading up to the clash against England during which the English camp threw a lot of jibes the Boks’ way.

“We never make excuses,” Kolisi said when asked about the long period the Boks spent in isolation and in bubbles. “We knew what we were up against this year. I am really proud of how the boys stood up to the challenge. We took it in our stride. We are so grateful that we are able to play the game of rugby. It’s been a tough year for everyone. There are many people who have lost jobs, who lost family members and we have the great opportunity of playing this game. And playing at a stadium [Twickenham] like this, it really has been a great honour.”

Related article:

When Kolisi speaks, you can hear he is genuine. He speaks of the collective rather than himself, and he constantly drives home the message about who the Springboks represent: not only those who can afford to watch them play live on pay television but every South African.

“I know I’m not the world’s best rugby player,” he says in the book. “I’ll never be remembered as one of the greatest ever, and I’m fine with that. All I care about is what kind of person I am. What am I doing to make sure that the next Siya doesn’t go through the same battles that I did?”

This isn’t just a rugby player speaking. This is one of the most inspirational symbols in South African culture – and Starling would have done better had he encapsulated that.