Sharp Read | Reflections on death

As a society, we are uncomfortable with death. But hidden in grief and tragedy is potential transcendence, if we allow ourselves to contemplate our own inevitable demise.

Author:

28 June 2022

I often run past a small, run-down cemetery. Recently, without understanding why, I stopped and entered, and spent an hour looking at the graves and reading the tombstones, some more than 100 years old and too dilapidated to properly decipher.

Does anyone still remember the people buried in the cemetery? There is a small church alongside, but my questions gained no response from the noncommittal, unhelpful reverend. Perhaps, contrary to my understanding of the pastoral role, she is more concerned with the problems of the living than the souls of the dead. Or maybe she sensed that I’m not religious, and not genuinely ready to engage about my salvation or the afterlife.

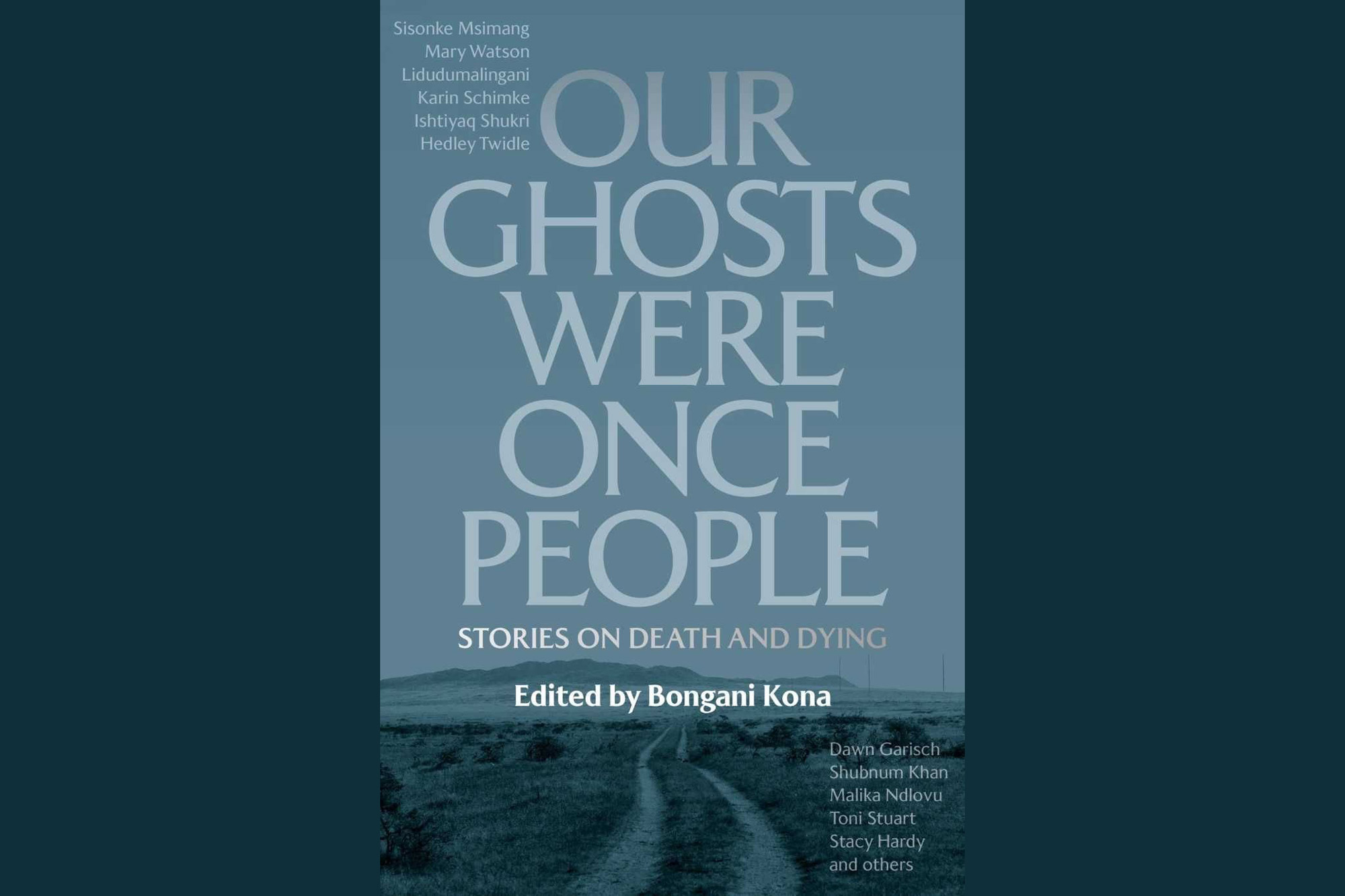

It was probably a coincidence that a few days later I started reading Our Ghosts Were Once People: Stories on Death and Dying (Jonathan Ball Publishers, 2021), a South African collection of short, non-fiction accounts of the process of dying, grief and musings on the possibility of a hereafter. Edited by Bongani Kona, the book is mainly about memories: forms of abuse by a father, what a grandfather was wearing when he died, the idiosyncrasies of a beloved sister. A death triggers an overflow of memories, before these, too, fade. My father died 25 years ago, and I have lost the ability to summon a vision of his face, or to remember what he preferred to wear, or how he spent his evenings. Instead, I feel these things. Some fabrics tingle on my skin like his old jerseys did when – just occasionally – he would make physical contact. Sometimes, reading in the corner of the living room under a dim lamp, I sense his pose in mine. And in the bathroom mirror I have started to shiver at the face looking back at me, gathering moles, spider veins and horny eyebrows. Who, exactly, am I looking at?

The cognitive sciences explain this as the subconscious intersecting with the brain’s executive control function. This happens during dreams; dream-thoughts are transitioning processes, Karin Schimke writes in The Favourite, her contribution in Our Ghosts Were Once People. Her ex-husband has had a dream about her father in which he urged her not to forget him. But forgetting is exactly what she wants to do, because her father was abusive, sometimes violently so. There’s no sense of forgiveness from Schimke. “Not everything that is lost is grieved,” she contends. In a dream of her own, he is throttling her.

Like Schimke, I’m sceptical of what dreams about deceased relatives mean. My sense is that people believe in ghosts or surrounding spirits because they do not want to accept the letting go of loved ones. That we carry our ancestors with us is a biological and neuroscientific truth – in our genes, our intergenerational post-memory – so why do we need to believe they are still with us in some state of personhood? Is this an imagination game, a whispering in death’s ear that we and ours will endure? Do we think death is fooled by our mocking pretence?

Aware that the concept of ancestral or other spirits is embedded in many cultures, I’m betraying my ignorance and bias. In Xhosa beliefs, for instance, the passage of dying is described as a homecoming (ugodukile), or alludes to a slow going down, like a sunset (ushonile), with the certainty of rising again to take a place alongside ancestors.

Many cultures, and all religions, convey this concept, that death is a portal to a different state of existence. In this metaphysical paradigm the afterlife is still a form of life; the living and the dead coexist and the dead remain in contact, speaking through dreams and portents – if the living are willing, and learn, to listen.

Opening myself to the possibility of ghosts or spirits, I still hit conceptual and philosophical walls, in any direction. Death, it seems to me, is either too randomly quick or too cruelly drawn out to have any meaning. Religions, beliefs, traditions – call them what you will – offer only rituals as coping mechanisms, and not any kind of explanation. Nor do they concretise an afterlife: how can omnipresent ghosts or spirits be real when they are demonstrably incapable of influencing us to act better towards one another, other sentient beings, and the planet? How can we have faith in a heaven or fear a hell given the real-life evidence of the state of the world? We are much haunted by the suffering of so many people in the here and now, on Earth – victims, just not dead yet.

Saying goodbye

Pain, suffering, endings: it is usually distressing to read anything themed around death. In an essay in The New Yorker, palliative care physician Rachael Bedard explains her role: “If you’re going to be useful to someone in that moment, it’s best if you’ve talked beforehand about what might happen. I learned to gently engage people in picturing their own decline and near-demise, and to ask what would be most important to them in those moments.”

Most of us would surely prefer to die at home, pain free, with loved ones close by, maybe with music playing. However, most of us simultaneously avoid contemplating and discussing these small aspects as part of the big issue. My mother, a former nurse, is in this kind of twilight zone. Now in her 90s, she talks openly of having “good days and bad days”. The good days are less frequent now, and she jokes about being “a useless old woman who will soon be gone”, an attempt at humour accompanied, repetitiously, by an earnest discussion about inconsequential things: reminding me where her will is kept, what to do with various trinkets – and “Oh!, what should I have for supper?” I don’t know how she would prefer to die, and I’m not sure she has voiced any thoughts even to herself. The arc of her life is fast bending downwards, and we’re running out of time. Inertia, too, is something of a disease.

Many of the stories in Our Ghosts Were Once People, too, are anecdotes of slow decline, people who were coping – until they weren’t. The dismaying part of this is the neglect of what Canadian palliative-care pioneer Ira Byock, in his book The Four Things That Matter Most: A Book About Living (Atria Books, 2004), says are the four tasks of the dying person and those soon to mourn: saying sorry, forgiving, saying thank you and saying I love you.

There’s a fifth, of course: saying goodbye. My father died unexpectedly, instantly, nowhere near any of his family. I wonder if I’m subconsciously processing a long overdue goodbye, one with an uninhibited intimacy not possible at the formal setting of his burial.

Self-centred grief

Distortion of memory starts straight after we lose someone. In a blurring of what was with what the mourners prefer to recall, the grieving brain is wrought with emotions, impacting and altering how we frame our reminiscences.

This shape-shifting nature of grief is beautifully explored in Nigerian author Yewande Omotoso’s new novel, An Unusual Grief (Cassava Republic, 2022). The main character is Majisola, mother of 20-something suicide victim, Yinka. Majisola and her daughter were estranged, and had never been close even during her daughter’s childhood. Majisola’s guilt and regret are now amplified by her daughter’s death.

Grief can be unusual, Omotoso shows us, because it is a transformative state, and brings unexpected perspectives. Stories expand, too, about someone we’ve loved and lost, as if a memory needs nurturing to stay alive, and the nurturing feeds upon itself. Majisola’s sorrow is also a journey of self-discovery, an unveiling of real feelings about her husband, her self-worth, the potential of her life ahead.

Related article:

Her grief also takes the form of living out Yinka’s life in the present by occupying her flat, wearing her clothes, concluding her business deals, and meeting her online friend and would-be lover under false pretences. The mother’s grief is driven by needs she can’t explain; part of her soul withers but, in parallel, her spirit enlivens, and even a sexual reawakening happens.

This blurring of pain and pleasure is what makes life beautiful, writes Susan Cain in Bittersweet: How Sorrow and Longing Make Us Whole (Viking, 2022). Life’s tragedies are inextricably tied to splendours, and we must embrace both in order to transcend either, and live a whole life. Referencing psychology professor Joseph Forgas, she maintains that “there’s something about sadness that removes the scales from our eyes”. Finding beauty and peace in the face of the inevitability of loss and suffering: this is the heart of the human condition.

Ignorance, apprehension and fear

Don’t we all obsess about dying? Whenever someone we know dies, a minor chord is struck, even if only faintly. When it’s somebody close to us, we hear the bell toll much louder. And as we ourselves age, the reverberations seem to creep agonisingly closer.

The psychology of Western death is predominantly one of fear. In Our Ghosts Were Once People, writer and activist Sisonke Msimang’s account, Years and Years, is a sequence of journal-like entries starting from when she was 12, the age at which she became acutely anxious about dying. Her father tries to comfort her by talking about God, but admits he doesn’t believe in God, so his final advice is “to stare her fear in the face”. Simply, life doesn’t teach us to die.

Would we fear death less if we faced it more? Journalist Hayley Campbell believes so. In All the Living and the Dead (St Martin’s Press, 2022), a non-fiction analysis of the various industries surrounding death, she attempts to understand the nature of those who get their hands dirty in finding out how people have died, preparing the body for its final resting place and masking or hiding what the living prefer not to see. Working with the dead – morticians and embalmers, coroners and criminologists, geriatricians and gravediggers – seems a bizarre job to choose. But someone has to perform these roles – literally, to make death vanish. Do we value, at all, the gravediggers, crematorium operators and undertakers – the real people who make the dead ready for their final farewell, and whose work then disappears?

Our Ghosts Were Once People includes an essay, A Death and Life Experience, in which Khadija Patel tells of her experiences as a young Muslim woman tasked with ghusl, the ritual washing of the body before burial. She found it spiritually rewarding. “And yet, as I’ve grown older, I’ve felt the unshakeable faith in the nearness of God waver … the longer I’ve lived, the busier I’ve become, the grime of this world has sometimes made me forget God’s nearness.”

The goodness in what people like her do is an aspect of A Terrible Kindness (Faber & Faber, 2022) by Jo Browning Wroe, based on the imagined psychology of the embalmers tasked with preparing the mortal remains of 140 children killed in the 1966 Aberfan disaster in which an avalanche of coal waste crashed down a Welsh mountainside and wrought death and destruction upon a junior school in its path.

Mourning the children

There are so many senseless deaths of children. In South Africa, shockingly, there were 352 child murders in three months alone between October and December 2021. “They don’t know me, and they don’t know my child. Why did they do it?” pleads the mother of a murder victim in Ways of Dying (Oxford University Press, 1995) by Zakes Mda. The same question is being asked by parents of victims of Russian bombs in Ukraine and of massacres in rural Mali and Niger. And how can we begin to understand the feelings of the parents of the schoolchildren murdered by a madman – and a mad, infuriating non-system of gun control – in Uvalde, United States, and imagine their unbearable loss, and how they will grieve for the rest of their lives?

The protagonist in Ways of Dying is Toloki, a professional mourner. He believes mourning is a vocation, a spiritual calling. “I cannot live without death,” he says to his dear friend, Noria, who suffers poverty as well as the loss of two children. She urges him to come and live with her in the shack settlement, because he’ll be very close to where he is most needed. “You will be coming home to where death is,” she points out. The novel is set in the early postapartheid years, when South Africa is riddled with violence: taxi warfare, gang attacks on trains, rural feuds transported into urban areas, and systemised killings as part of a destabilisation strategy by apartheid’s still flickering forces.

Noria and Toloki are empathetic souls, but violence, rape and murder have become so commonplace that even they discuss it nonchalantly. “Death lives with us every day. Indeed, our ways of dying are our ways of living. Or should I say our ways of living are our ways of dying?” Toloki laments.

His mourning for strangers is also a metaphorical mourning for the country. Ways of Dying was written more than 25 years ago. Has much changed?

This question is an undercurrent of Damon Galgut’s Booker Prize-winning The Promise (Umuzi, 2021). It’s an astonishing novel, an allegory of the resurrection and fall of South Africa since the 1986 State of Emergency, bookmarked by the deaths and funerals of four members of the dysfunctional Swart family based on barren land outside Pretoria. The mother’s death is sad; the father’s is ridiculous. As the years tick by the three children gain no comfort, or their comfort amounts to nothing. Their lives are unappreciated, and seen as valueless even by themselves. Dreams wither and potential is unfulfilled as a slow burn, ersatz depression takes hold of them, a stasis awaiting their respective fates. We sense that for some of them death is not only inevitable but may also be a blessing.

And Fate sends portents of what may happen as a consequence of a promise not being kept. A dove flies into a glass door and dies. Is it the mother’s spirit?, some of the family members wonder around the dinner table, reminding them that the deathbed promise made to her so long ago – that their domestic worker and her carer, Salome, would be given a home – has still not been fulfilled.

The narrator, omnipresent and all-knowing, may also be a ghost or spirit. He or she alternates between ambivalence to death, disgust at its processes of bodily disintegration, and caustic, droll commentary on the absurdity of rituals – not only surrounding death, but also of the fabric of the country, the way we live.

The religiosity woven into the four funerals is almost sneeringly described. Spirituality is beyond the Swarts, whether Christian, Jewish or the vaguely Buddhist utterances of a yoga instructor called upon, ad hoc, to say something meaningful at the cremation of the son who has died by suicide.

There’s almost nothing redemptive. The last surviving family member, Amor, eventually fulfils the initial promise made to her mother and Salome, but it’s 34 years too late, and the value of the promise has withered. Amor was 11 when her mother died; now a menopausal 45, the hot flushes persistently warn of her own descent towards the inevitable. “You’re drying slowly in your channels, running out of sap. You’re a branch that’s losing its leaves and one day you’ll break off. Then what? Then nothing. Other branches will fill the space. Other stories will write themselves over yours, scratching out every word. Even these,” says the narrator. What has been true for Amor’s family will be true for her. And for all of us.

How to die? How to live?

Msimang’s story, Years and Years, also reveals a different dimension to feelings of sorrow. When she gives birth, she feels a strange sense of fear for her newborn, how her daughter will have to cope in her own lifetime with climate change, environmental degradation, the threat of nuclear apocalypse. “I feel these tragedies in my womb,” she writes. “This love is a new kind of grief and in her first hours of life I begin to mourn a sadness that is yet to come.”

It’s the essence of the beauty of birth: epitomised by a tiny baby, we grasp how fragile this life is. This ephemeral, finest of lines that hedges our proximity to mortality is disquieting and unnerving – which is why we try hard not to think about it.

Sometimes, though, incidents – can a death be called that? – hit very close to home. At my local Cape Town coffee shop recently a woman suddenly died at the table while having refreshments with her daughters. This may be a good way to go, doing something pleasant and unaware of what is about to strike. Like my father, walking his dog – and then he wasn’t. People who witnessed his last moments told us it was over very quickly. Which doesn’t lessen the shock of the first few days of bereavement, but is a comfort in the weeks that follow, and the hollowness of not being able to say goodbye has a counterpoint that takes the shape of a blessing as I grow older myself, and hear of or see more and more acquaintances who face death slowly, sometimes in great pain.

Memories resurface: I’ve suppressed thoughts of three friends I lost a long time ago. They were too young, and were hit by dreadful diseases, one by pancreatic cancer, the others both by motor neuron disease. There is so much literature – by ethicists, moralists, religious scholars, in the Bible or Quran or the Torah – but so few answers, if any, to explain the point of this slow suffering, nor why we should tolerate it.

Only a handful of countries legally permit either euthanasia or assisted dying. Switzerland’s non-profit organisation Dignitas is probably the most well-known clinic, which, according to its website, is committed internationally to help with “the last human right”.

We should re-examine our assumptions about the institutions and customs associated with death and dying, especially in established religions or those that prevail in Western conventions: mortuary slabs, the euphemism of a sterile funeral parlour, hospitals and hospices. Too often, life is prolonged at too much human cost. Some religious leaders are shifting towards more choice about how to reduce suffering and improve dignity. So often willing to take a principled and forerunning view, Archbishop Desmond Tutu announced in 2014 that he was in favour of assisted dying. Two years later, when he turned 85, suffering from prostate cancer and recurring infections, he went a step further: “I hope I am treated with compassion and allowed to pass on to the next phase of life’s journey in the manner of my choice.” Tutu fought passionately for dignity for the living, in South Africa and elsewhere. “Dignity is a God-given right,” he wrote. “Now, with my life closer to its end than its beginning, I wish to help give people dignity in dying.”

In the first part of Mayflies (McClelland & Stewart, 2021) by Andrew O’Hagan, two best friends grow up together in an industrial town in Scotland, slipping into rustbelt, recessionary decline triggered by the Thatcher years. Although Jimmy (nicknamed Noodles) is a bit younger and quieter than Tully, they’re both rebellious, zestful and have ambitions for a better life – to which they escape as soon as they can.

Part two picks up 30 years later. They live in different cities now, but have remained close. Tully calls with bad news: he has terminal stomach cancer. He wants to die on his own terms, and he asks for his best friend’s help to do so, and his companionship in going out with a bang. The book’s first section is a riot of youthful exuberance; in unravelling how Tully feels, the second is ridden with pathos. “Of course there’s panic, and serious thinking about how to die. But there’s also the desire to remain in life and continue enjoying its wonders. It’s a combination of high anxiety and tranquillity – and pleasure in small things,” he says.

Towards the end of Mayflies Tully can barely eat or drink, but humour prevails. “So, Noodles,” Tully asks at a high-class restaurant in Switzerland, close to the Dignitas facility, “is this where socialists come to die?” “No, only to dine,” Jimmy replies. “What’s a consonant between pals,” Tully counters. It’s not quite the last word, but the friends are close to losing their Scottish stoicism as time runs out and death’s door starts to darken.

The story is elegiac yet uplifting, and the book’s title itself is a metaphor: a mayfly – a subspecies of dragonfly – is an ephemeral creature, living as an adult for only a day. Mayflies is a book about how the process of death could be, and a lesson for how we should cherish life’s friendships. If you read the book and remain unconvinced of the right to die with dignity you have a cold heart – and I hope your rigidity is never called to bend for you or yours.

Is the end the end?

Musings about death tend to disintegrate in the vacuum of extreme suffering. Sometimes dying and its associated loss are inexplicable, like stillbirths, or the terminal illness of an infant or young child for whom seizing remaining time or seeking comfort in the faith of an afterlife are irrelevant and beyond their comprehension.

I wonder what happened to Emma in 1886, in then-named Protea Village, Cape Town. Hers is the oldest gravesite in the cemetery I visited, and she is the youngest entombed there, having died at just four years old. A few other tombstones make note of another struggle, remembering community leaders for their resistance to forced removals from Protea Village. These are more recent graves, from the late-1960s. If their occupants’ spirits were dampened, if not ruined, in their lifetimes, they may soon be at peace: a large tract of beautiful land adjacent to the cemetery, just below Kirstenbosch Gardens, has been earmarked for rezoning, part of which will be used as restitution for 95 of the families evicted from the area more than 50 years ago.

Staring again at Emma’s grave, I ponder whether loss, suffering and grief do, then, have some kind of resolution. Inexplicably, my eyes prick. It must be the cold wind, I think.

Postscript: The little cemetery has been mowed, tended and tidied since I wrote this article. A few dozen more graves have been revealed and, remarkably, a few of their old tombstone encryptions can now be deciphered. A fresh bunch of flowers has been placed on one of the graves.