Sharp Read | Reflecting on apartheid’s hard knocks

The stories of two South African men with widely differing backgrounds and life trajectories have points of convergence that are perhaps not surprising, given the times in which they have lived.

Author:

2 November 2021

Two new memoirs call back South Africa’s past, and cry out for a better future.

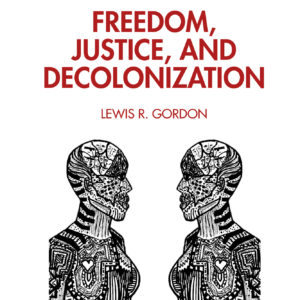

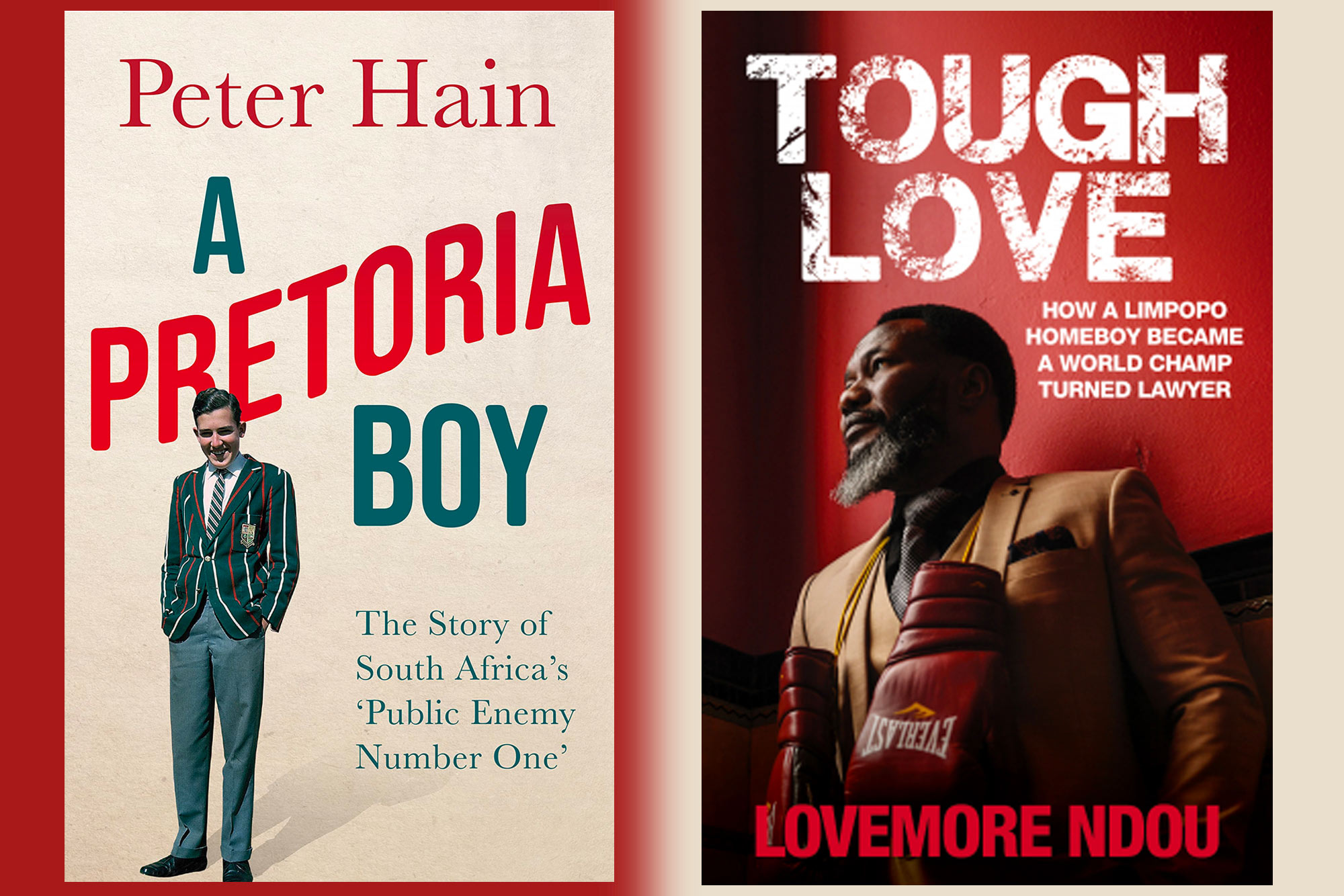

Followers of the global boxing scene aside, most readers will be more familiar with Peter Hain than Lovemore Ndou. But here are two fighters, roughly of the same generation, one a politician, the other a pugilist, both capable of brilliant strategy and tenacious tactics in pursuit of their goals.

A Pretoria Boy (Jonathan Ball, 2021) incorporates Hain’s early life, touches on how he became a British member of Parliament and Cabinet minister, and reflects on his more recent role in helping to expose state capture in South Africa. Mainly, however, it dives deeply into his activism as a lens to understand some of the wide-ranging anti-apartheid – and continuing – struggles of the past 50 years.

The introductory chapter covers South Africa’s fall from sense in the Zuma years, spotlighting Hain’s role, in 2017, in drawing the United Kingdom Parliament’s attention to the endemic corruption. The section is mundane, boastfully styled and seems written for a British readership. Reorienting the timeline to his early boyhood, he portrays an active, balanced, middle-class upbringing, a happy family. This was soon in serious jeopardy.

Related article:

Hain’s parents grew increasingly outraged at apartheid’s injustices and immoralities, and by the late-1960s they were immersed in political opposition bordering on the illegal. Here, we feel Hain understates their fearlessness, which was extraordinarily atypical of whites in that era. Their involvement deepened; his mother was banned, his father fired from multiple jobs owing to his support for progressive causes. Then they were both jailed, when Peter was just 11 years old.

From this point, A Pretoria Boy becomes riveting, a dramatic story of all-in commitment and no small degree of bravery in contributing to the anti-apartheid struggle. Fitting the subtitle The Story of South Africa’s “Public Enemy Number One”, Hain explains how he strove to boost awareness and resistance using the potent lever of sport, starting with militant “direct action” demonstrations against the Springboks’ rugby tour of Britain and Ireland in 1969-1970.

By then his family was in exile. The events culminating in their departure comprise a harrowing chapter about the sentencing and hanging of schoolteacher and anti-apartheid activist John Harris. Even readers familiar with the history of Harris’ trial and sentencing may not know of the sordid state plot paralleling his actions.

Early immersion in politics

Harris had planted a bomb in the whites-only section of Pretoria Central station in July 1964, but he had phoned multiple authorities to warn them in advance and urge them to clear the station. The security forces did not intervene – a decision from the very top, by the then justice minister John Vorster, in order to deliberately engineer white deaths at the hands of a white “terrorist”. Harris was rapidly convicted of murder and hanged in April 1965. Poignantly, a 15-year-old Hain delivered the eulogy at Harris’ cremation because his banned parents, close friends of the activist, could not.

Thus, inevitably, Hain became a political animal early in life. His beliefs were further cultivated and shaped into activism in London. At 17, disappointed by the Labour Party’s “abject timidity” on the issue of the then Rhodesia’s unilateral declaration of independence, he joined the Young Liberals, the youth and student wing of the Liberal Party, “because they were a vibrant, irreverent force for radicalism”.

As an erstwhile Pretoria Boys High pupil, he was sports-mad and understood the essence of how sport, and specific codes therein, stirred the passions of white South Africans. “International sport, whether the Springboks, the Olympics or a cricket tour, gripped the white nation as nothing else,” he writes, underscoring how it gave legitimacy to the apartheid regime.

Related article:

Disrupting sporting links would force whites to contemplate their government’s moral foundations as well as their own roles in propping it up. It wasn’t pioneering thinking, as it built on the concept and efforts of Dennis Brutus, co-founder of the South African Non-Racial Olympic Committee, which had successfully lobbied for the country’s Olympic ban in 1964. But it was Hain who grasped the need for greater dynamism through combining emotive opposition with physical protest, both to catalyse media attention and prick international conscience with a far sharper needle.

The latter, he correctly points out, could not be assumed. Hain reminds us that this was a time when London (and Washington) chose to align with racist, brutal regimes as long as they opposed communism: “It was easier to achieve success through practical protest against sport links than it was to secure sanctions by taking on the might of international capital or military alliances. Victories in sport were crucial during a period when internal resistance was being smashed and it was extremely hard to impose international economic and arms boycotts.” (There’s a triumphant passage later in the book in which Hain wryly recalls the hypocrisy of the politicians who were on the wrong side of history – and morality. After 1990, they all wanted to be in Nelson Mandela’s orbit, including Margaret Thatcher, who, when he addressed the UK Parliament in July 1996, “scuttled down to the front, having denounced him as a terrorist only a few years previously.”)

Cunning strategies

This, then, was Hain’s brilliant strategic insight: the direct action of playing field invasions, protesters chaining themselves to goalposts, hurling flour bombs into the on-field action, hijacking team buses. Escalating provocation surrounding high-profile sport served as a microcosmic representation of something far more seriously wrong – deadly wrong – in South Africa.

Hain’s other defining attribute was pragmatism, a willingness to prioritise progress and action even if it compromised the purity of his position. So, he clandestinely met – separately – with cricket and rugby supremos Ali Bacher and Danie Craven, two staunch supporters of the status quo, and used the opportunity to urge them towards desegregating their codes and softening the edges of how sport was played on the ground.

His colleagues in organisations such as the British Anti-Apartheid Movement would have disapproved of this as compromising the tenet that there could be no normal sport in an abnormal society. But, with the benefit of hindsight, multiracial sport was one of the early catalysts for change, an aperture through which a different society could be glimpsed.

Related article:

Hain’s activities harnessed an enormous network of contacts and connections, and spurred the enmity of an equally large – and more powerful – contingent of establishment operatives, both in Pretoria and London. So, his stories fluctuate between the motivations and minutiae of his activism and the machinations of his enemies. The latter included major malevolence, even murderous intent, such as his family’s fortunate escape when he was targeted by a letter bomb at his flat in Putney, London. By fluke it failed to detonate, but it was a reminder of the long, evil arm of the apartheid regime.

When the balance of forces are measured across internal resistance movements, Umkhonto weSizwe and other freedom fighters, the negotiations and machinations of exiled political leaders, the role of capital through eventual disinvestment and economic sanctions, could it be that the most wounding for white South Africans was the shutdown of international sport? If that is even partly true, Hain’s leadership and hands-on role deserves accolades.

As a memoir, it’s natural that Hain often centralises his role in events. As a politician first and foremost, his tone, at times, borders on smug. But this generally prevails just briefly before he credits others, often generously. And we have to admire his particular brand of courage and commitment.

Body blows

By comparison, Tough Love (Jonathan Ball, 2021) is the life story of a comparative unknown. Born in 1971, Lovemore Ndou grew up in the northernmost Limpopo town of Messina (now Musina). As a child of the time and place, his formative years are sadly predictable: forced isolation, township poverty, near-zero prospects, subjugation and state persecution. This was the harsh, localised and lived reality of what Hain, from far away, was fighting to change.

Segments of the first half of the book are tragic; one, when he witnesses atrocities committed upon his grandparents’ village just across the border in Zimbabwe during that country’s war of liberation, is horrific.

As a youngster, Ndou cradles his dying best friend, shot by police. Later, deemed guilty of a petty theft he didn’t commit, he endures months of imprisonment and brutish corporal punishment. His beloved mother dies; his father is driven to alcoholic despair and Lovemore interrupts his attempted suicide. There are a few anecdotes of happier shades of normality – adventures with his brother, discovering a love of learning – but these are sporadic intermissions in the longer descriptions of suffering. “By the age of fourteen … I barely even valued my own existence anymore,” he recalls.

Related article:

Ndou’s emergence as a boxing talent is, like so many in this most combative of sports, born of necessity as basic streetwise protection. Then, when his inner rage at life’s inequities causes his constant expulsion from football matches, a mining security guard is watching. “Why don’t you try boxing?” he advises. “I don’t think you have much of a future in football. You’re never on the field long enough.”

The guard invites Ndou to train at the compound’s gym, and soon his first amateur fight is scheduled. Ripples of concern spread through the community about a 14-year-old featherweight being matched against an experienced 24-year-old welterweight. Some urge the bout’s cancellation. But, still numbed by the circumstances of his friend’s death, Ndou remembers that “my own mortality seemed of little consequence to me. I didn’t care if I got hurt, didn’t care if I died.”

He knocks his opponent out inside one minute. It’s a pivotal minute, the juncture at which he recognises boxing as his golden ticket to a better life. “It instilled a belief that I could achieve something and be somebody,” he remembers. And so begins the journey towards greatness: “I didn’t want to be known as the local champion, or someone who won a provincial title. No, I wanted to become a world champion.”

A double-edged sword

Dreaming big, Ndou moves to Australia to further his boxing career. But Australia isn’t the end of abuse and abnormality. The sordid world of professional boxing, with its fickle administrators, corrupt hometown referees and judges, and shady promoters – “some managers and promoters would sell their own mother for a dollar” – presents less life-threatening but nonetheless major systemic obstacles.

He is effectively blackmailed by his promoter, who is also his immigration sponsor. “I’ll pull your application for residency at the Department of Immigration and put you on the first plane back to South Africa,” threatens the legendary but ruthless Bill Mordey.

Getting lied to, manipulated, being at the mercy of fight fixers: Hain may relate to this as politics in sport, but of a different kind. It became obvious to Ndou that in Mordey’s stable he was a workhorse, mandated to fight for limited returns and minimal global exposure, and never in line for a world title bout. Refusing to give up, he knuckles down to see out the remaining two years of his contract. He also commits to building a life after boxing by studying as intensely as he trains.

Related article:

His optimism eventually pays off, both academically and in the ring. By the time of his retirement in 2012, Ndou had garnered three world titles and six academic degrees, and now has his own law firm in Sydney. He was inducted into Australia’s boxing Hall of Fame in 2019; strangely, his achievements aren’t widely acknowledged and celebrated in South Africa. The book could have gone further in rectifying this by post-scripting his full professional record – the narrative around his world title bouts, in particular, is hazy and seems incomplete.

In typical boxing tradition, Tough Love includes rich veins of snappy phrases and wisecracks: one of his shifty promoters is “as slippery as a vapour trail”; on his first trip to fight in America, in Atlantic City, he wants to go for a training run but “the cold would snap an Emperor penguin”; “I swapped left hooks for law books,” he says about transitioning to a new career.

This makes for enchanting reading, and Ndou comes across as likeable and sincere. He wants his story to encourage young South Africans to prioritise education. “One of the reasons I wrote the book is to inspire the youth. The biggest message I wanted to send is that nothing’s impossible. If you put your heart, soul and dedication into it, the dream can become a reality,” he said at the book’s local launch.

From dreams to dust?

A Pretoria Boy and Tough Love are, overall, similarly enthralling. Hain’s memoir reminds us how hard the fight for democracy was in South Africa; Ndou’s cues attention as to why this was so: the violent repression, the inhumane security apparatus, the daily struggle. As a record of what it was like to live in the belly of the beast, Ndou’s tale is raw, the memories less filtered, tragic, yet uplifting. Hain’s is crafted, more multifaceted, edited to shape his brand, perhaps, but nonetheless also inspirational.

Both, too, are poignant in their recording of dismal chapters in history as well as overcoming personal and familial hardship, only to have been let down again. In Hain’s case, this is owing to state capture and corruption in the ANC as an organisation he still cherishes, while in Ndou’s it is the limited recognition of his achievements and the lack of real economic opportunity in his homeland. Mandela looms large in both memoirs, a lodestar for both men. Says Ndou: “…it saddens me to see all the hard work he did, even sacrificing his life in custody, for 27 years … fighting for a better South Africa, but then today, I see all that going down the drain.”

Related article:

But they remain optimistic and believe their respective books can contribute to renewal by, for example, helping people understand the anti-apartheid history. “You know, we haven’t told our people, younger generations, what apartheid was all about, what happened to bring about change. This lack of understanding is plaguing us,” Hain said at the virtual launch of his book.

Ndou, meanwhile, is pondering returning to South Africa, maybe to enter politics. “The first thing [I’d do] is to see that every child is educated, and that free education really means free education.”

These are hints that their respective legacies may not be complete, that they are both still seeing wider contexts, itching to act. Hain admits to being concerned about the future of global politics: “Many of the things we thought we’d achieved – greater equality and social justice – are being rolled back. Brexit, Trump, Putin, Bolsonaro, the so-called big men of global politics, they’re rolling back a lot of the progress that was won through generations of struggle by trade unionists and progressive political action. So we’ve got to keep fighting.”

Ndou, it seems, is still ambitious and still a dreamer; Hain remains a pragmatic activist. Both are still fighting the good fight.