Sharp Read | One Marechera, two points of view

The vastly different perspectives and treatments in two recent books about Zimbabwean author Dambudzo Marechera leave the reader with tantalising questions beyond the subject matter.

Author:

25 May 2021

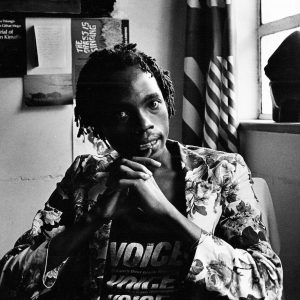

My first encounter with Dambudzo Marechera is at assembly at an out-of-the-way rural boarding school. I was twelve. At this point I don’t know his story or reputations. His gender is fluid. For a while he stayed a woman in my imagination. He is not a man. Androgynous. – Tinashe Mushakavanhu

My first encounter with Dambudzo Marechera is in a country to the north of South Africa. I am 30. Marechera has just died. At this point, everything I hear from comrades about his books and his personality makes me conclude I am never going to read him.

For a while, in my imagination, Marechera stayed a privileged, sexist, male writer who could choose a risky lifestyle that would glorify him – glorification that would earn women vilification for similar behaviours. In my mind I heard “personality cult”.

My first encounter with Tinashe Mushakavanhu’s work is through his joint project with graphic designer, educator and associate professor Nontsikelelo Mutiti, Some Writers Can Give You Two Heartbeats, published in 2019. The book stands out, first because of its unusual cover, which features its table of contents, and second because of its richly nuanced pages of multiple layout designs, photographs, font types, newspaper excerpts and handwriting. And last because of its encyclopaedic ambiance and the carefully selected quotes that make it an easy, quick yet kaleidoscopic read offering multiple insights and lessons on Zimbabwean writers. Mushakavanhu is a creative writer-cum-literary scholar-cum-cultural activist.

Related article:

To encounter his scholarly creativity this time, through Reincarnating Marechera: Notes on a Speculative Archive (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2020), is to engage with another product of in-depth archival and curiosity-driven research. Reincarnating Marechera is 59 pages of “notes”, compared with the 258 pages of Some Writers, and is part of the 2020 Pamphlet Series of commissioned essays on poetics, translation, performance, collective work, pedagogy and small-press publishing.

My first encounter with Flora Veit-Wild is through a literature journal just under two decades ago. I am reading a piece she has written on Marechera. As years go by and I continue to read, I realise that this German professor of African literatures and cultures is a Marechera scholar. My current encounter with Veit-Wild is through her 279-page book, They Called You Dambudzo: A Memoir (Jacana, 2020).

These two texts on one writer are phenomenally different. My interest is to engage them in a conversation of sorts, rather than make a comparison. I want to place the two next to each other in order to share with the reader what this side-by-side view shows. Reviews on both have already been published. A review of Reincarnating Marechera written by Stephen Scott Whitaker was initially published in The Broadkill Review in August 2020 and updated in December 2020, while Lizzy Attree’s review of They Called You Dambudzo was published in Africa In Words in February 2021.

Recently, Marzia Milazzo had their review of They Called you Dambudzo published in the Mail & Guardian at the end of April. It is not my goal to rehash these; I only give each a nod when necessary. For instance, I am curious about Whitaker’s first review, which I never read. What did he need to add, delete, rephrase or reorganise? What really prompted the December update?

Reconstructing versus remembering

While Mushakavanhu reconstructs a life, Veit-Wild remembers a life. Both actions are inherently subjective. The reconstruction and the remembering unfold in the recently independent Zimbabwe. Whereas reconstructing seems to broaden and recreate, remembering seems to solidify and confine. Both scholars are deliberate about incorporating verifiable evidence into their texts for readers to see their objectivity. The facts and minutiae of detail that each scholar chooses in order to craft their story and the narrative arcs each one centres on Marechera expose textual tonalities worthy of an in-depth study. My reading of these tones is understandably subjective because we all bring our pasts into reading any text.

Mushakavanhu’s reconstruction of a life does not end upon Marechera’s death. Reading Reincarnating Marechera comes across as Mushakavanhu saying: “Tell me whatever you know about Marechera, I am listening. My eyes are open, show me anything. Teach me.” Veit-Wild’s remembering also continues after Marechera’s death. Reading And They Called You Dambudzo comes across as Veit-Wild saying: “I knew Marechera well, listen to what I am telling you. Look at what I have done to honour him. Believe me.” This, of course, should be expected, because Veit-Wild’s memoir is a personal stamp of authority on her former lover and a revisitation of a time gone by. Memoirs are, after all, windows into lives and their design rests with their writers.

Mushakavanhu’s project is an intellectual one – it is searching, asking questions, looking and relooking, piecing together information fragments, positioning and repositioning. It is work in progress, as the pamphlet’s subtitle suggests. Reincarnating Marechera has readers diving into Marechera, the writer and person, in five sections: “Machine of Death”, “Imagination Library”, “Literary Shock Treatment”, “Epistolary Anarchy” and “Abstracts”. Through these notes on a speculative archive, this reader started anticipating reading a book by Mushakavanhu that will stand spine to spine with Viet-Wild’s They Called You Dambudzo.

Related article:

Veit-Wild’s project is a personal one – it is a public presentation of an “own” story, an answering of questions, a positioning. Attree writes in the opening paragraph of her review that “this memoir does not primarily focus on Flora herself, beyond being written from her perspective, and it remains essentially the story of love lost and a kind of haunting”.

Fiona Lloyd, a Zimbabwean journalist and editor, one of the eight people who wrote a blurb for this memoir, describes it as “[a] memoir that subverts time and geography. Veit-Wild’s account of her relationship with Dambudzo Marechera – the greatest African writer of his generation – is both a celebration and a lament… Their dance is beautiful and destructive. Ultimately it is redemptive. Reader, prepare to be unsettled.”

Was I unsettled? Well, yes, I was. Would I have been unsettled in the same way had I not read Mushakavanhu’s pamphlet first? And They Called You Dambudzo was a disturbing read. Mushakavanhu’s pamphlet confirmed my discomfort and provided context and offered words to express this unsettlement.

Scratching the archives

The Marechera archive that Mushakavanhu has navigated is in “Berlin, London, Pietermaritzburg and Harare” and he calls his pamphlet “my own scratching”. He outlines three types of archives on which his “scratching” is based. First is “the archive of Dambudzo, the subject himself … his actions and his autobiography”. Second is “the critical archive driven by Flora Veit-Wild and the European academy”. And third is “the imaginative archive”, one he suggests “is important”.

Mushakavanhu’s commentary on the second archive is worth quoting in full: “Second, there is the critical archive, driven primarily by the biographical work of German scholar Flora Veit-Wild and the European academy, engaging with Marechera in a way that makes him optimal for consumption. Though they do much to keep Marechera alive and visible, they also bury him amid a sequence of affective and theoretical presumptions that take away his black agency and participate in a process of forgetting him altogether. What we have is a carcass, remnants on which they built their version of the African writer infected by European philosophy and theory to a point where he has no identity and is unrecognisable as himself.” (My emphasis.)

Related article:

I read Reincarnating Marechera in 2020 and the idea of him being reduced to a carcass stayed with me for long, a very saddening stay. While reading They Called You Dambudzo in 2021, I hoped for a resuscitation of this carcass. However, I was constantly reminded of the presumptions that Mushakavanhu mentions. He asserts that while the driver of the Marechera archive is Veit-Wild, she has the “European academy” behind her.

If Mushakavanhu is correct, what does it mean to have an academy behind you? How does it manifest in practice? Put differently, how do Africans interested in the archives negotiate our research journeys? Common sense suggests that the curators of an archive do so through their own subjective reading of the content to be archived. The context of the curation also matters and often it has an impact on the decision-making processes.

In her prelude, Veit-Wild pays tribute to her lover through memories of their times together. Titled “I REMEMBER”, this list of 18 italicised “I remember[s]” reads like a stamping of one’s authority, an irrefutable claim, a declaration in two parts: I knew him. He was mine. It starts with “I remember our first night…” and ends with “I remember waiting for the next gasp, each time thinking: Is this the last?” In this prelude, Veit-Wild summarises her relationship with Marechera through distinct scenes of connection, romantic intimacy and innuendos of sexual intercourse. This is how she sets the scene of her memoir and then the window opens wide as the text paces through six sections titled “Trajectories”, “Harare in Heat”, “Eaglets of Desire”, “Heaven’s Terrible Ecstasy”, “Bastard Death” and “Entangled Legacies”.

Differences in treatment

Towards the end of Veit-Wild’s prelude, we read: “Your waistcoat is now a cultural artefact here in Berlin at the Dambudzo Marechera Archive of Humboldt University. Marechera mummified, as someone joked.”

In the opening of Mushakavanhu’s first section, “Machine of Death”, we read: “Dambudzo Marechera has never left. He occupies a special place in [the] Zimbabwean imaginary. The miniature of his existence continues to inspire wild conjecture, despite his early death on August 18, 1987, aged 35.”

Here is an example of the differences in how the two scholars write about Marechera’s flat at number 8 Sloane Court. From Mushakavanhu we learn that Marechera used this bedsit as a meeting place, “…one of the central nodes for his social network as a writer-intellectual”. Marechera hosted writers, journalists and expatriate visitors, very much like Can Themba is known to have done at his home called House of Truth in Sophiatown. Mushakavanhu ends “Machine of death” by grounding Marechera at this flat. This physical grounding simultaneously opens Marechera up to the world as we read about how this physical space – his accommodation – was in fact also a space of collegial connectivity.

Related article:

Veit-Wild’s chapter on number 8 Sloane Court runs over six pages. We read about how she and Victor and Marilyn Poole pulled funds together so “…our protégé writer was able to live in Sloane Court until the time of his death”. We read about how Veit-Wild sewed the curtains to the flat herself. We read about details: the hip flask that belonged to her father, her mother’s diary, titbits about Germany, the Nazis and the Jews, the Rhodesians, her sons and related memories and her engagements in the literary scene. In this amalgamation of intimacy-evoking memories, Veit-Wild asserts that Marechera’s time at Sloane Court was for her “…the most pleasurable and most satisfying period in our time as lovers”.

Both scholars’ writing styles are engaging and pace through the pages invitingly, and they both insert Marechera’s poetry into their texts. Veit-Wild’s choices are often poems that Marechera wrote about her or their relationship, or both. For Mushakavanhu, the focus is on Marechera’s activism and how he challenged Robert Mugabe’s politics. From Veit-Wild, readers get a sense of what the lives of expatriates were like.

Both scholars delve into the literary scene in Zimbabwe during this period. Through Mushakavanhu, we learn how Marechera orbited within the literary spaces, the impact of his personality on the youth, his activism and how his writings continue to live with Zimbabweans. Through Veit-Wild, we learn about the impact Marechera had on her as a person, how her literary career started and how he became the subject of her career. Reading Mushakavanhu feels like he is saying, “Come, walk beside me, we are together on this journey.” Reading Veit-Wild feels like she is saying, “I am the leader, follow me.”

The changeling

“Who is Dambudzo Marechera?” asks Mushakavanhu as he introduces readers to his pamphlet. As he ends the first section, he asserts, as he answers his own question: “He changes with every memory, every retelling. If Dambudzo Marechera had not existed, Zimbabwe would have invented him.”

I am reminded of how Frantz Fanon wrote about culture in colonised countries. In The Wretched of the Earth, he posited that there are three phases that writers in colonised countries undergo. I quote what he suggested is the final phase: “Finally, a third stage, a combat stage where the colonised writer, after having tried to lose himself among the people, with people, will rouse the people. Instead of letting the people’s lethargy prevail, he turns it into a galvaniser of the people. Combat literature, revolutionary literature, national literature emerges.” (My emphasis.)

Marechera’s first book, House of Hunger, was published in 1978 when his country was called Rhodesia, while his second, Black Sunlight, came out in 1980, the year of its liberation. Mindblast was published in 1984, three years before his death.

Related article:

In Reincarnating Marechera, Mushakavanhu details ways in which Marechera became the galvaniser of Zimbabweans, how he roused them and how he has continued to do this posthumously. Writing about this posthumous reverberation in the section he calls “Epistolary Anarchy”, Mushakavanhu notes: “There is a glaring absence, however, of female correspondents in this archive, suggesting a phallocentric nature of the black radicalism Marechera represents.” Reading this reminded me of my first encounter with Marechera that I share above.

Marechera died when Mushakavanhu was four. While Marechera’s generational mission of rousing and galvanising Zimbabweans as a writer, activist and public intellectual is presented persuasively in Reincarnating Marechera, Mushakavanhu’s chosen generational mission of excavating stories, resuscitating stories and reconstructing narratives in order to guard against the erasure of Zimbabwean – notably, not Rhodesian – writers is self-evident through his literary projects. Mushakavanhu writes about aspects of his journey in Letters Zimbabweans wrote to Dambudzo Marechera.

Related article:

The frequently quoted Fanon, writing in The Wretched of the Earth that “[e]ach generation must discover its mission, fulfil it or betray it, in relative opacity”, raises questions. Why these two books? Why now? Is there no Zimbabwean publisher keen to publish books on Marechera? A pamphlet on a Zimbabwean life is written by a Zimbabwean scholar and published in the United States. A German scholar’s book on the same life is published in South Africa. The “most comprehensive source on Marechera and his legacy” is to be found in an archive in Germany, Veit-Wild informs readers. Mugabe, whose politics Marechera challenged, died in 2019, a year before both texts appeared. Do these nodes of connectivity suggest anything, or are they coincidences?

What, then, do readers make of what these two texts reveal? The perspective in the Mushakavanhu pamphlet prompts numerous questions; unsurprisingly, Whitaker likens him to a “literary detective”. In the memoir, on the other hand, the romanticised yet dysfunctional and seemingly toxic heterosexual relationship of the Veit-Wild perspective reveals a colossal full stop. I agree that Mushakavanhu feels like a detective, and to me Veit-Wild feels like a judge. I heard the constant sounds of stamping as I read her book. Milazzo suggests in her review that Veit-Wild is a capturer. The sentence from Milazzo that the “animalistic images that Veit-Wild uses to describe Black people cannot be overlooked” invites readers to an analysis of the nature of this capture.

Like the reviews noted here, the two texts on one Zimbabwean writer invite us to ask numerous questions as we read. These questions seem urgent to me, in this moment. How do readers concerned with the ideas and work of decolonisation use such texts? What is uncovered through reading such texts and therefore encouraged regarding writers’ archives and legacies? What is the political significance of these two texts, today?