Sharp Read | Losing ground in the promised land

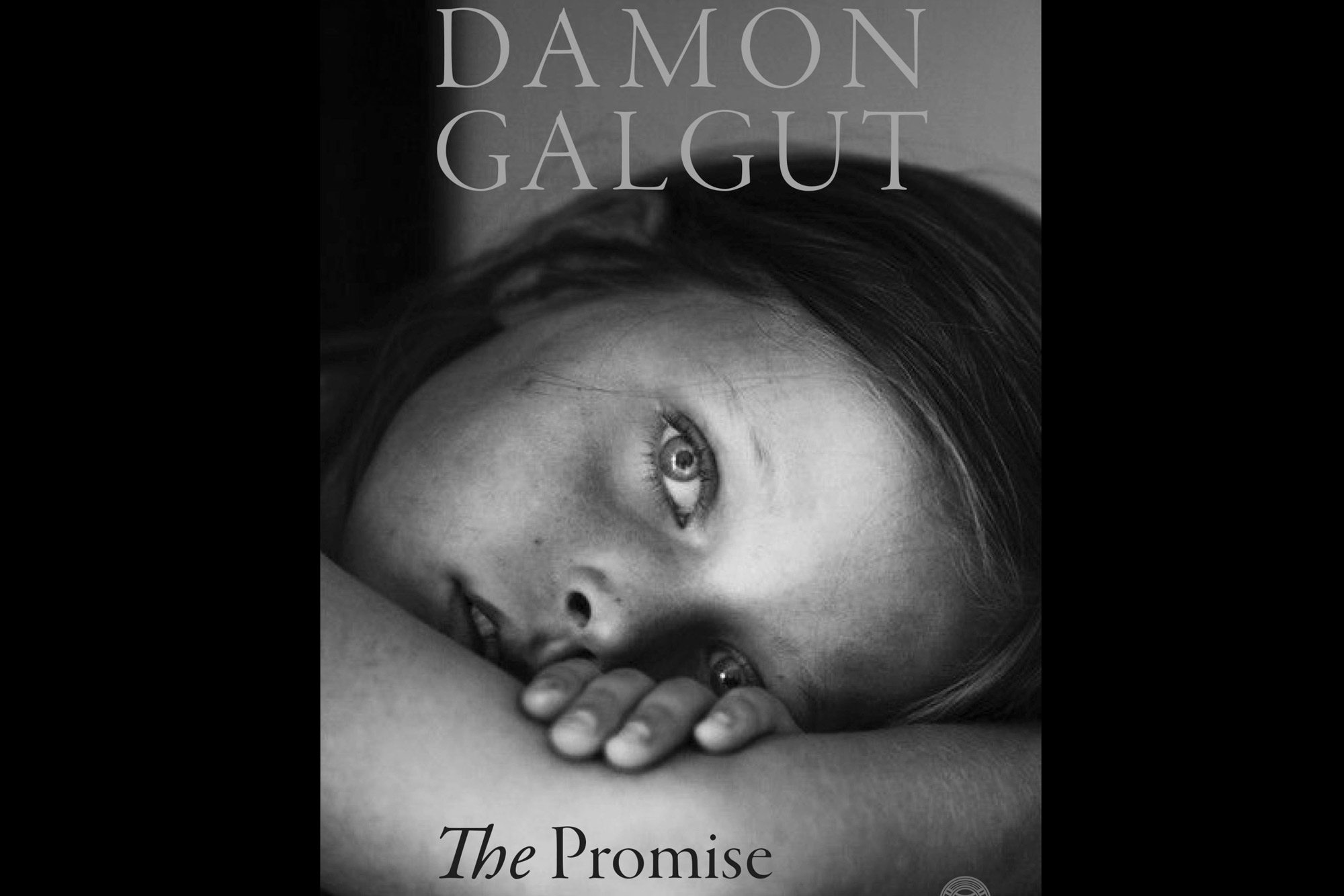

Damon Galgut’s use of irony in his Booker Prize-nominated new novel, The Promise, toes the line between the ironic and the allegorical in masterful fashion.

Author:

14 September 2021

For three years I’ve forsworn South African literature. I realise that might make me a badly read reviewer, but after a five-year period of immersion in a particular corner of it, I was well sick of the woe and seriousness, and the dull, often badly written and either sanctimonious or guilt-ridden plots that plodded through farms and cities alike. So I was surprised to find Damon Galgut’s novel The Promise about four funerals over four decades in South Africa both refreshing and funny.

The story follows the Swart family – the choice of name is one of many surname jokes – as they slowly dwindle. The plot hinges on a promise that Rachel, the mother, elicits from her husband to give the domestic worker who nursed her, Salome, the house and land she lives on. Amor, the youngest of their three children, witnesses the promise.

But when she brings it up to her father, he scoffs. It is 1986, and Black people cannot own land in South Africa. So the promise is kicked down the line, from sibling to sibling, who squabble and prevaricate, never quite getting down to the logistics of giving Salome the land she was promised.

Related article:

The farm is no prize – even the family agrees on this, calling it a worthless piece of land. Nonetheless, they hold out, living in a house extended until it is a labyrinth of many rooms, full of doors.

Over the hill, in a falling-down cottage with earthen floors, live Salome and her son Lukas. Three more deaths and 30 years pass in this fashion, as Salome makes the trip back and forth from the big house to her cottage, growing old while her son works as a labourer on the farm. Little changes for those left on the land, as they warily circle one another and the buildings fall into disrepair.

The name of the character who will die introduces each of the book’s four sections. Part of the pleasure of reading this novel is finding out who dies how, so if you want to experience that, stop reading now – there are spoilers ahead. The novel is both the study of a white family’s relationship to race, land, power and each other, and an allegory for the country.

In sickness and in death

The mother, Rachel, dies of a disease that wastes her body, probably cancer – a long and terminal ailing that likely reflects the country’s sickness during apartheid. Though her husband wants her buried on the farm, she asks to be placed in the Jewish cemetery, having reverted to her family’s faith after she fell ill.

The death of the father, Manie, 10 years later is from a snake bite he gets as part of a stunt at his reptile park. He is attempting to break a record for “dwelling among serpents” as a test of his faith in God to protect him from the Devil and to raise funds for a church. This is during the wild years of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the 1995 Rugby World Cup; acts of faith, good and bad, all around. A blind, incestuous pastor who manipulated Manie into giving him some of his land buries him in the Calvinist tradition. Lukas and another man, Andile, dig the grave on the farm.

The middle child, Astrid, dies during Thabo Mbeki’s term. She gets pregnant young and marries a farm boy. But she has an affair with the man who installs her security and, after marrying him and ascending to the higher echelons of elite power, she has an affair with his Black partner in the security firm. She is killed in a hijacking, shot for her Mercedes, and buried in a Catholic ceremony by the priest who withheld her final absolution on the day she died.

Related article:

Anton, the eldest, dies by suicide at the moment Jacob Zuma resigns. He is ruined by alcohol and a 20-year attempt at shaping his thoughts into a novel. His marriage is loveless, his friends are few. He goes on a bender and kills himself almost on a whim after gambling his money away at Sun City.

Only Amor is left, strange Amor, who goes to Durban to tend the sick, washing the people dying from Aids during the Mbeki years, never having children (though at one point wanting them), living for a time with a woman, but ultimately ending up alone.

Her body’s flowering opens the novel: her first period arrives at her mother’s funeral, forcing her and her sister to miss the proceedings. It also closes it: her last period comes right around the time of Anton’s death. The novel ends with her having a hot flush – “you’re drying slowly in your channels, running out of sap”. She, like the country, has reached middle age.

Breaking the fourth wall

Allegory can be hard on the nerves, especially if the bodies of women and Black people are made to carry it. But Galgut uses irony to make the literary nature of the work apparent, playfully exploring the tensions in the ethics of representation.

At three inflection points, the beleaguered, doomed Anton bumps into a fellow conscript in the South African Defence Force. When Anton is leaving the military base after hearing his mother has died, he is stopped and asked, “What do you want?” This is perhaps the key question for the character. “I want your gold and your women,” Anton answers, playing the colonist, but then changes his mind and says, “I come in peace, take me to your leader,” shifting to an alien.

He tells the soldier he killed his mother. The day before he shot a woman in a township and the two have become overlaid in his mind. (This is also a foreshadowing of what takes place when he fails to uphold his mother’s promise.) Anton asks the soldier’s name and is told it is Payne. “We’ve met before,” Anton says. “Are you an allegory? Are you real?” He holds up his hand and surrenders to “Private Payne”.

We laugh at Anton meeting his private pain in the dark outside his barracks. It works, in part, because it uses play to express something unspeakably heavy without being sneering. These kinds of nods and winks to the audience can be overbearing, the writer caterwauling, “Get it!?” at the poor reader, or else the writing can be so layered that it vanishes up its own allusion.

Related article:

But Galgut walks the line. We meet Private Payne twice more: Anton returns to base after the funeral but at the last moment decides he cannot go back, and Payne is his witness. He leaves for the “jungle”, first to Transkei then Johannesburg. Much later, on the night before his death, Anton meets Payne in a seedy bar. In the 31 years since they last saw each other, Payne has a career, two grown children and a wife. So perhaps he wasn’t an allegory after all, or else Anton’s pain split off from him and lived a life of his own, an ordinary life. Anton is bored by him and wanders away to his death.

Before this, at a morgue, Anton is met by someone named “Savage” and he muses: “You’d think you were in a novel.” Similarly, the Catholic priest “blurting out his distress” wonders why people never mention going to the toilet, even though everyone does it several times a day. “No character in a novel ever does what he is doing now … One way to be sure you’re not a fiction,” he thinks.

The characters wondering if they’re fictional or assuring themselves they’re not reminds us that we’re reading a story and that the author is toying with us. Because of this, we can forgive what might otherwise be heavy-handedness.

Narrator and reader

The author’s playfulness comes out in the floating narrator, who is almost a character in its own right. An impish spirit, it constantly shifts perspective, giving us a scene from the outside and then slipping inside a character’s head – sometimes in a single sentence: “But tonight her brother, from his high place, seemed to notice me.”

Through this (not quite) omniscient narrator, we’re given glimpses into the characters that are both horrendous – the private moments (a Jewish body washer inserting a suppository) and the private thoughts (a tumescent undertaker thinking he shouldn’t imagine the grieving women too hard in these pants) – and funny.

At other times the narrator drifts away from the characters and starts giving numbers: cups of tea drunk and litres of urine flushed at a funeral, for example, or the respective heights and weights of a couple of detectives. The numbers add up to nothing, or nothing significant, which is perhaps the point. The facts of any particular moment can never quite give us the full picture.

Related article:

The sections with numbers don’t appear often, but when they do, the story teeters. It is whipped together again only at the last second as the reader is whirled over to the next image or inserted into the next mind, which is thrilling but also comes close to making the whole thing disintegrate. Yet it is joyful, like being taken around in a bumper car.

The narrator seems to lose control of the narrative at times, as though it were a poorly trained dog. At one point it begins to follow a homeless man it dubs Bob, then after two pages it wonders why this “unwashed raggedy man” is “obscuring our view”. “Why did he waste our time with his stories?” the narrator asks, calling him a self-centred egoist and telling the reader to pay him no mind.

But in this way, the beggar arrives at the reader’s window, “insistent on being noticed”, somehow hijacking the narrative and forcing the narrator into telling his story – a story on which the narrator never seems to have a firm grip. “Let’s say they’re sitting around a dining room table. Or … in the lounge. Or out on the front stoep … It doesn’t matter.” It is almost as though we are reading an early draft of the book, the characters slipping from room to room, still too hot and fresh to settle.

The interlocutor

There is also an interlocutor, a second-person “you” the narrator is addressing: “They’ll be drinking and making bawdy jokes soon after you go too” – as in, soon after you die. There is an inferred reader, who, at different points in the book, seems to be a middle-class white woman: “If you glance over there, but not right now, you’ll see that hot politician, can’t pronounce his name, those tongue clicks are too difficult.”

This inculcates and makes the reader complicit in both obvious stereotyping and more subtle forms of overlooking, pivoting mostly around Salome.

At Astrid’s funeral in the Catholic church, Salome, who was barred from attending both Rachel and Manie’s funerals, can only make out smudges of the ornate gold interior because she has cataracts, “which give her a wise, aloof demeanour”. Earlier, Anton imagined her as “childlike”, calling her “an old child, with a weak heart”, after which Anton’s wife calls her “incredibly lazy, that old one”.

Related article:

Wise, childlike, lazy: these racist images are projected onto Salome by the people around her through the wily narrator/author (who is likely tipping his hat to JM Coetzee’s plaasroman) and thus subtly by the inferred reader, making for some uncomfortable reading.

When Salome begins to look forward to going home to her village outside Mahikeng, the narrator chastises the reader: “If Salome’s home hasn’t been mentioned before it’s because you have not asked, you didn’t care to know.”

A larger story is hinted at as the narrator calls attention to the unasked questions of the “invisible” domestic worker, a prop in homes and literature alike: Who is this woman? What is her story? Yet we are not given an answer, at least not by Galgut, who expressly chose not to delve into the minds of his Black characters.

Who cannot be known

Galgut said in an interview that he was giving the white perspective and so made the conscious decision not to enter the minds of Black characters. When the floating narrator gets to the Black characters, it begins to lose some of its swagger, loading sentences with words such as “perhaps”. When Lukas strips down to wash after burying Manie, the narrator describes him: “His long dark body is ridged with muscle, a pink scar zigzags across his back. Some private history there, don’t know him well enough to ask.”

We can see his body, his private small moments, but we cannot penetrate into the intimacy of his inner life. We are kept out in a way we are not with the white characters, who we watch on the toilet and whose minds pour forth their cruelty, their shame. There seems to be a yearning to know and yet an impossible barrier is held up.

Related article:

It is the job of writers to work imaginatively, to give us the world, but to do so carefully and ethically. (The debate about who can – or should – write what is typified on one side by Jonathan Franzen, who will write only white characters, and on the other by Lionel Shriver, who considers all material hers to work with and calls censorship what others term cultural appropriation.)

Is it possible to imagine and write another perspective – to do this necessary work – without causing harm? Or is violence inevitable from the white male perspective within the remit of power in the publishing industry and in the country and world at large, no matter how careful and reflexive it is?

A cautious choice

Galgut seems to believe the latter, erring on the side of caution by giving us an all-access pass to whiteness but holding himself apart from blackness he cannot, or dare not, enter. This is a fraught choice: after all, the narrator gives us even the perspective of the dead, yet it cannot imagine the mind of a Black person?

Later we are shown Lukas again, but this time he is “a pot-bellied man in tracksuit pants and vest, bald on top, beard below … Something about him that’s half ruined, in kinship with the house.” The house has not been worth the fight. Amor thinks, “This. For this my family held out.” Bitterness, petty cruelty, twisted rage has brought everything to the brink of collapse. Even Amor’s offering of the deeds of the cottage is a poisoned cup: the land has a claim on it. Salome could lose it anyway.

Lukas says to Amor, “It’s not yours to give. It already belongs to us. This house, but also the house where you live, and the land it’s standing on. Ours! Not yours to give out as a favour when you’re finished with it. Everything you have, white lady, is already mine. I don’t have to ask.”

Related article:

With this, he articulates the great fear that lives, like a domestic worker, with much of South Africa’s white middle class: always around, carefully ignored. Standing at this abyss, Amor appeals to Lukas, asking him to remember their shared history. He says nothing.

On this terrible end falls the highveld rain, indiscriminately touching the rich and impoverished alike, wetting the parched earth and bringing with it a kind of relief – like “some cheap redemptive symbol in a story”.

Robyn Bloch is a doctor of English literature. Her PhD, from the Wits Institute for Social and Economic Research, looked at complicity and betrayal in apartheid perpetrator narratives written after 2010. She now works as a subeditor for New Frame.