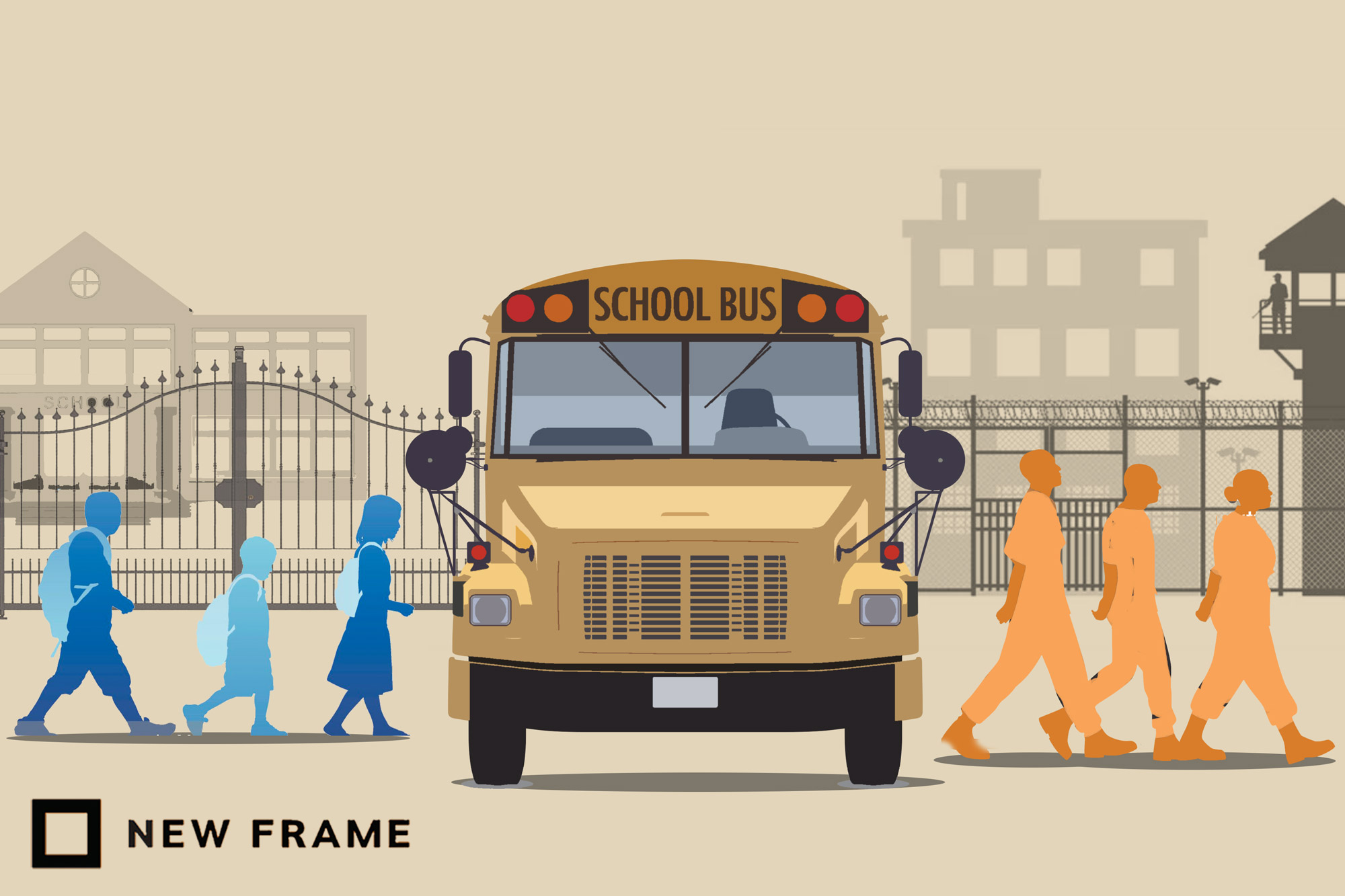

School-to-prison pathways raise a red flag

Instead of helping children overcome bad behaviour, some schools have a zero-tolerance policy, which may push learners into the criminal justice system. Many struggle to return to school.

Author:

16 March 2022

On 3 March, the Constitutional Court heard argument in favour of decriminalising the use and possession of cannabis by children. The legal debates at issue have weighty implications for children across the country. But, as we have argued elsewhere, the facts underlying the case also raise red flags over the ways that schools’ decisions in disciplining learners can create school-to-prison pathways in South Africa.

The term “school-to-prison pipeline” has been used to refer to education policies that directly or indirectly bring learners into contact with the criminal justice system. There is some recognition of the need to disrupt such pathways in South Africa. For example, education legislation expressly prohibits the direct referral of learners to the criminal justice system following a school-administered drug test. Instead, schools are required to engage with the learner’s parents and pursue options such as drug counselling. Despite this explicit legislative prohibition, the case of S v LM and Others exposed failures to meet this mandate. The case uncovered shocking details of a programme being implemented by school officials and prosecutors in Krugersdorp schools that effectively funnelled learners straight from their school and into the criminal justice system.

Related article:

In one school alone, the so-called “Drug Child Programme” led to 178 children being referred to the criminal justice system following a school drug test. Of these, 24 children were eventually sentenced to “compulsory residence” at Child and Youth Care Centres (CYCCs) for indeterminate periods under diversion orders.

This was the fate of the four boys who would be at the centre of the S v LM case. The boys tested positive for drug use at their school after eating a dagga cookie and they were ultimately detained under compulsory residence orders at CYCCs. The Gauteng high court held that such detention was not provided for by the Child Justice Act (2008) and, considering the minor offence at issue, amounted to a form of “cruel, inhuman and degrading punishment”.

The case highlights an alarming failure by school officials, prosecutors and magistrates to comply with legislation, and the devastating impact of direct school-to-prison pathways on children. The case also raises red flags over punitive and exclusionary school discipline policies more broadly, which, even though lawful, may contribute to indirect school-to-prison pathways.

Critically under-researched

There has been limited scholarly attention to the link between disciplinary measures at school and criminal justice interaction in South Africa. Other jurisdictions have shown that punitive and exclusionary measures have the effect of marginalising children from the systems of care and support that are intended to help them. Learners subjected to exclusionary disciplinary mechanisms, such as suspension and expulsion, also often experience significant barriers to returning to school once their period of suspension is completed, fall behind academically, and are at significant risk of dropping out of school and of consequently encountering the criminal justice system.

Research shows that punitive exclusionary practices do not, in fact, reduce or prevent future recurrence of similar transgressions. Yet, a zero-tolerance approach to school discipline tends to be the prevailing norm in South Africa. Learners are often suspended or expelled for relatively minor infractions, sometimes without due process. As attorneys from the Equal Education Law Centre have noted: “Despite the provisions of the Schools Act, schools often suspend pupils as an automatic or default response to misconduct.”

Alternative approaches to punitive and exclusionary practices are needed to ensure that at-risk children, like the boys at the centre of the case in S v LM, are supported rather than merely punished for rebellious behaviour at school. While there must be consequences for problematic behaviour, restorative interventions should encourage and facilitate at-risk children to learn appropriate behaviour for the future. To do this, a whole-school approach that is based on preventative and restorative discipline should build partnerships between communities, schools, surrounding support networks as well as law enforcement to meet the aim of prevention rather than punishment.

Related article:

Substantial changes are needed across the education system. Codes of conduct, training and resources should be founded on, and prioritise, restorative interventions. While these interventions may face resistance from school stakeholders as time-consuming and as yielding limited immediate results, research from other countries has shown that these approaches can be successful.

What transpired in S v LM offers a stark reminder of the detrimental impact of direct and indirect school-to-prison pathways on children. It also highlights that the legal issue which is now before the Constitutional Court takes place in a much wider social context, with severe consequences for young people who are brought into contact with the criminal justice system despite the fact that the law says that they should not be. The facts of the case highlight that we need behavioural interventions for children that are focused on prevention rather than punishment, and that the decisions that are made in applying discipline should always be guided by the aim of advancing their best interests.

Nurina Ally is a lecturer in the faculty of law at the University of Cape Town and former executive director of the Equal Education Law Centre, a public-interest law organisation based in Cape Town. Robyn Beere is the deputy director of the Equal Education Law Centre. She is the former director of Inclusive Education South Africa, an organisation specialising in advocating and building capacity for the implementation of inclusive and supportive school environments. Kelley Moult is an associate professor of criminology at the Centre of Criminology at the University of Cape Town.