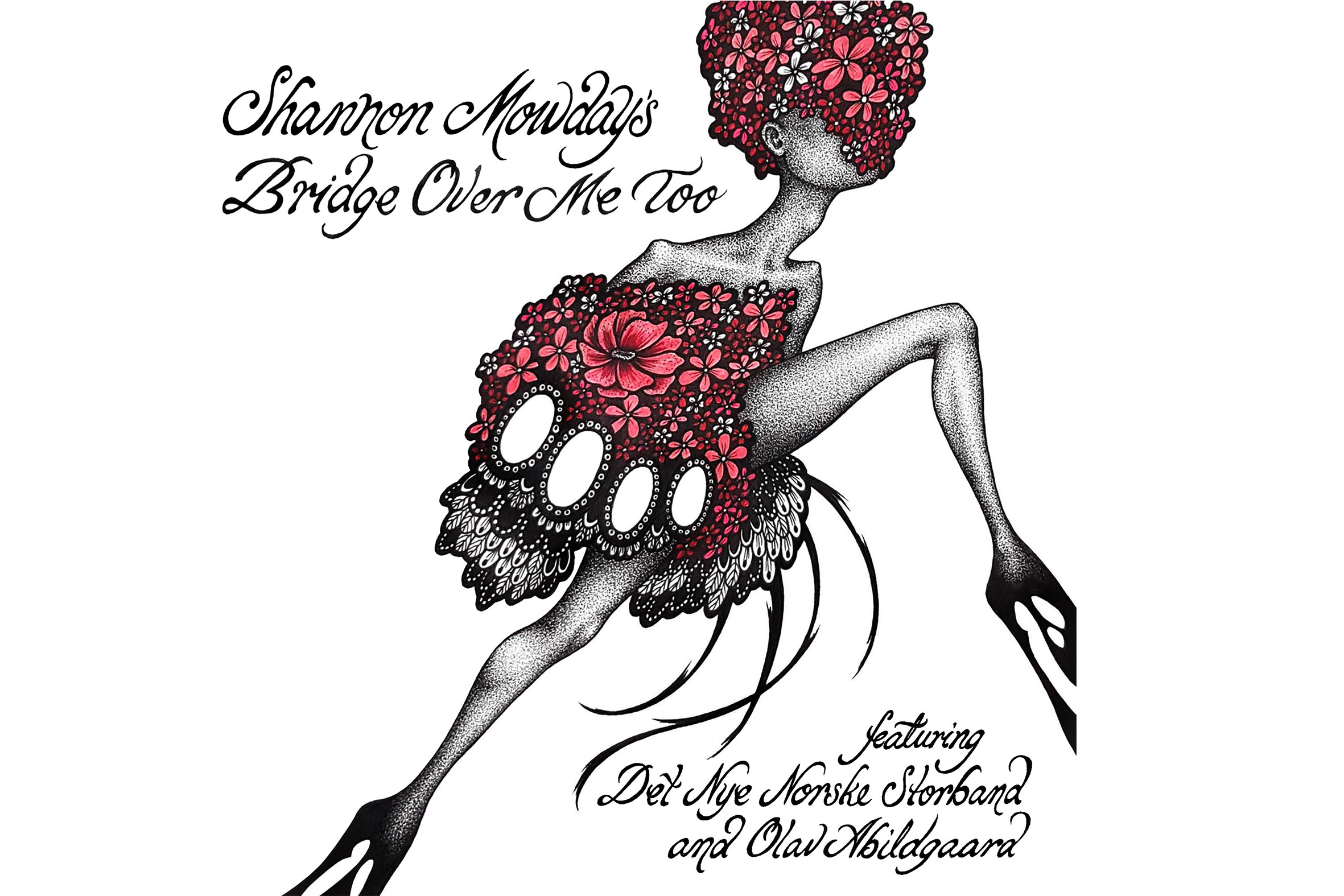

Saxophonist Shannon Mowday bridges the gender gulf

The multidisciplinary initiative Bridge Over Me Too works to confront the sexist prejudices of jazz classrooms and stages to create space for everyone.

Author:

18 May 2022

“If all you know is what and how you were taught,” says saxophonist, composer and teacher Shannon Mowday, “that’s what you’ll do too.”

Cape Town-born Mowday is currently based in Norway, where she leads the Akershus and Oslo Youth Jazz Orchestra (AOJO) run by the East Norway Jazz Centre. She also works as a freelance player and music director and has been a part of collaborations in Europe, Australia and South Africa. She’s discussing her multidisciplinary initiative Bridge Over Me Too, developed primarily in Norway over the past 18 months. But it has roots in – and plans in process for – South Africa too now that pandemic travel restrictions have eased.

Through workshops and performances, the project works to dissolve the exclusionary binaries that can make jazz classrooms and stages hostile environments for young women, LGBTQIA+ musicians “and anybody else who isn’t part of the boys’ club. You can’t just force girls into a guy environment; the point is to create a new environment with space for everyone.”

“Who’s your daddy, girl? / Is he famous? … / Who’s your boyfriend? / Oh, it’s HIM – I say, he can play! Oh yes, he can play!” run the lyrics of one of the project’s singles, illustrating how women musicians are persistently seen in terms of the men around them. But Bridge Over Me Too is more than a set of songs: it’s also a platform for processing experience and a blueprint for teaching and performance practice. Its genesis in South Africa dates back more than a decade.

Mowday, who was the 2007 Standard Bank Young Artist for Jazz, was first drawn to register for a master’s degree in improvised music in Norway by musicians she met at the National Arts Festival in Makhanda, then still Grahamstown. “I thought this [approach] is so different. It focuses on your own voice. I heard it in action and followed that trail.” Once in Norway in 2009, away from everything familiar, she was forced to think more about who and what she was.

“On the one hand I was getting all these stereotypes from some Norwegians about how they thought ‘playing like a South African’ should sound. I needed to share that South Africa isn’t only that. Often outsiders only have an idea from the musicians who left. They don’t realise how much has happened since, or know our free jazz legacy.

“But I also realised that back in South Africa I’d tried to be ‘one of the boys’, playing harder and faster and louder. And yet that wasn’t me. I recognised the parts of me that had been damaged through those years of fighting. Who am I? I’m a South African, but not in some obvious musical way outsiders want. And I’m a woman. And I’m a single mother.”

A woman’s perspective

Studying, playing and then teaching in Norway, and taking music projects back home from there deepened and developed these insights into increasingly explicit practice. Gender inequalities among musicians exist everywhere. “My son’s father can just pack up his instrument and tour; few organisers consider my need to arrange and pay for childcare.” But South Africa’s horrifying levels of gender-based violence – and the fact that organisers here often did not even ensure safe, late transport for their musicians – intensified the issues. “I left South Africa not feeling safe as a woman.”

However, “this is never just about music or gender alone. It’s a societal thing.” In 2020, Mowday’s Lila quartet album The Land In-Between marked the callous murder of Cape Town toddler Courtney Peters with a tribute composition. “And when I played it in South Africa and talked about the situation, some men walked out.”

Through her own South African performing and teaching years, from subsequent collaborations and classes with South African women musicians and later an online chat forum, shared experiences of exclusion, exploitation and harassment were piling up “and they were devastating, awful. I couldn’t bear the weight of them.”

Related article:

Alongside threats and actual instances of sexual violence, the discourse ranged from the predictably patronising (“so you can actually play, for a girl”) through slimy innuendos (“wow, I bet you give good blow jobs”) to direct insults from a male musician to a female counterpart (“this is what we do: play jazz and fuck girls like you”).

Some change, says Mowday, is now happening here, in education and on stage – “sharing experiences does have a positive impact” – but slowly and incrementally. That’s why she believes Bridge Over Me Too also has to enact and encourage different approaches to teaching and playing. “And it can’t simply be about empowering women. You have to reach the guys too.”

Mowday points out that gender-nonconforming male musicians – and those who simply don’t aspire to Play Like a Boy (as another Bridge Over Me Too composition phrases it) – also suffer from the industry dominance of patriarchal stereotypes and from sexual predation.

Hungry and eager

South Africa has huge musical strengths, she believes. Alongside their unique jazz voice, “young South Africans have an energy, power and hunger that’s lacking [in Norway] where getting music education is relatively easy.” She talks about a moving moment in a South African class when a young man stopped playing to say, “I’m so sorry you had to go through this …”

“How do we get away from these binaries? It has to start young. Between 13 and 16, these networks and attitudes form. Boys hang out, drink beer they’re not supposed to and listen to music. Where do the girls fit in?”

Such networks and attitudes persist into the cadre of professional decision makers – the “gatekeepers”, as Bridge Over Me Too calls them. Gatekeeping can be direct, in setting the standards for acceptable playing by exclusive reference to limited, male, musical role models (“and they’re often not even South African”, as Mowday observes). Or it can be far more indirect. A new collection of transcribed South African standards (a “real book”) has just appeared and “out of 116 composers only four works are by women – me, Miriam Makeba, Dorothy Masuka and Melanie Scholtz”.

A short documentary on Mowday’s work with the AOJO begins to show what change might mean. Band members describe how Mowday’s approach balances nurturing a personal voice and building a collective spirit. She writes “parts that demand you make choices”, but also that let you “take care of each other and want each other to sound good”. In Mowday’s time with the orchestra, it has grown from having two female players to “almost half, and numbers overall need a second ensemble”.

Where the conventional teaching approach is often simply to distribute standard charts that all the young musicians must follow, Mowday says she “shapes my music around the players, for what I know each individual has. I use imagination, scenes and metaphors they can relate to. In every class – I’m running an improvisation class for classical musicians at the moment – it’s about how do I get you to feel comfortable.” It takes time, emphasises Mowday, and projects like Bridge Over Me Too can only ever be a starting point.

“In South Africa, when I teach like this, sometimes people call it the Norwegian way. But I see it elsewhere. For example, my son’s Montessori schooling is also about giving structure but space for freedom and difference within that structure. And for me, that’s ubuntu!”