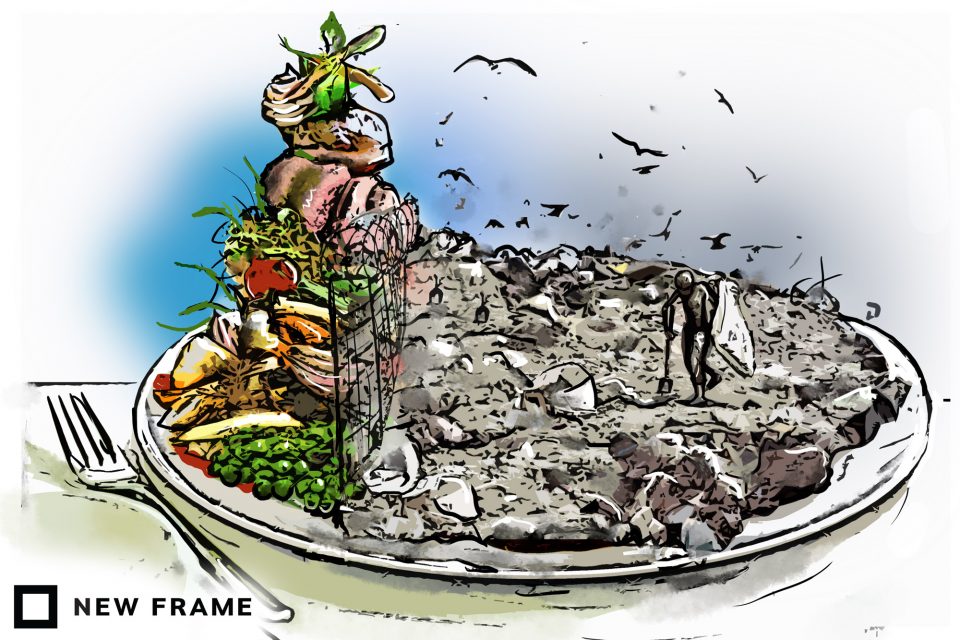

SA’s impoverished excluded from inequality debate

South Africa’s economic policies have been moving to the right, embracing big business and ignoring workers and jobless people. Why does no organised voice speak out against this?

Author:

10 May 2021

There is something missing in South African politics and public debate today – a loud and organised voice campaigning against poverty and inequality.

This absence is particularly surprising at the moment. Of course, poverty and inequality here are not new. The disparities between huge wealth and grinding poverty have been a feature of South Africa at least since the late 19th century when super-rich Randlords (mine owners) lived in mansions while working people risked their lives underground for very little pay. But the problem is particularly stark right now.

When Covid-19 reached this country, we heard confident predictions that economic and social life would have to change for the better because the pandemic had shown how costly this country’s economic inequities are. But, if there has been change, it has been in the opposite direction – life has become even harder for most.

The evidence shows that the economic costs of the virus have been largely borne by the usual victims, people who are already worse off. As the economist Neva Makgetla pointed out last week: “Less skilled workers lost more livelihoods; small businesses were more likely to close down; and government cuts to services disproportionately hurt low-income households and communities.” The most recent budget shows that the government has no intention right now of helping out people living in poverty. Its priority is attracting investment and it believes it can do this only by cutting spending on social needs. This threatens to reverse policy since 1994 which did recognise that fighting poverty should be a priority.

Related article:

The absence of resistance to these shifts is stark. Except for a few newspaper columns or comments on digital media, there are no mass campaigns demanding that policy begin to take seriously the economic needs of the majority. There was a time in this country when inequities were greeted by marches, stayaways and boycotts – today they attract a newspaper column or two and a few rants on digital media.

One sign of this absence is that public-sector trade unions reacted to the only pay freeze since 1994 by going to court and hoping for the best, not by mobilising. While there is talk of a strike this year, the government would have to offer a very small increase to avert it. The revealing point is that the reason union strategists are prepared to accept very little is that they believe public opinion is against them. Since the majority of the public are people living in poverty, this either means that unions believe that most poor people don’t support their demands or they believe that people living in poverty are not part of the public.

No strong voice against poverty

The governing party is paying no great price at the polls for any of this. By-elections since Covid-19 arrived – the most recent were in mid-April – show that some ANC voters may be staying away but not enough to prevent it winning wards from its opponents. If current trends continue, the ANC is set to do as well in October’s local elections as in 2016 – or better.

So, at a time when millions in townships, shack settlements and on farms probably need support more than ever, the lack of opposition means that current policies are sure to continue and that the pandemic will leave most people worse off than before. Why is this? Why in a country in which the language of social justice and criticism of economic-power holders is common political currency, and in which movements which campaigned against poverty and inequality have been part of the landscape for over a century, is there no strong voice demanding that the economic needs of most people become a priority?

The most obvious reason is a huge gap between those who claim to speak for the poor and marginalised and the people on whose behalf they aim to speak. Some grassroots movements do speak for people in poverty in their areas but they are not strong enough to launch national campaigns. With this exception, people who bear the brunt of poverty are not organised and none of the political parties and non-governmental organisations who claim to speak for the poor have ever put down the sort of roots in areas where most of the people live, which would make that claim credible.

Perhaps the only movement in the country’s recent history that has spoken for an organised national following of people in poverty is the trade union movement. But the unions always only spoke for people who had jobs and, despite much talk about linking up with the jobless, there was little action. And, over the past few years, unions have been severely weakened, mainly by a reality in which the gap between the lifestyles of the leadership and those of members has grown as many of the leaders have become part of the problem they were meant to fight.

But this may be merely a symptom of two deeper problems. The first is the country’s continued division into insiders and outsiders and the reality that the insiders monopolise politics, in parties and in citizens’ organisations. The second is that the country’s racial divisions continue to shape its politics.

One important feature of the country’s politics is that, despite glaring poverty and huge inequalities, there is no strong party here to the ANC’s left. The SA Communist Party and the Economic Freedom Fighters would no doubt claim this role but they are both, in different ways, part of the nationalist family which is designed to act against racial inequality but not the gap between rich and poor. The most recent attempt to organise a left party here, by the National Union of Metalworkers, made no headway.

Related article:

The country’s racial past and present ensures that, despite its decline, the ANC is still the dominant force among most voters and there is no sign of this ending. Only a party which seems to come from within the broad traditions of the ANC will win mass support. The ANC is not only central to most voters – it is also why social justice activism is so removed from the grassroots. While most activists reject the ANC, they are often fixated on it, more concerned with why it does not listen to them than with organising people.

Nor is there much history here, outside the union movement, of effective campaigns for greater economic or social equality in which race is not a central issue. There is a history of boycotts, mass rallies and stay-aways in areas where the poor live. But they have all been part of the fight for racial equality. So, what is now missing – a campaign against poverty rather than against racial injustice – has always been missing.

The strange gap in this country’s politics is deeply rooted in history, which is why it is so hard to change. But that does not mean it can never be changed. That most people have never been able to be heard on economic issues does not mean they must be ignored forever. When and how these realities will change is unclear. But, as long as the economic debate remains the preserve of a few, progress to a fairer society will be very limited indeed.