SA’s cash-strapped rowing team defies the odds

Coach Roger Barrow explains how he has turned one of South Africa’s most underfunded sporting codes into a successful crew.

Author:

28 August 2019

From a distance, Roodeplaat Dam looks like a sparkling blue jewel. Up close, however, the abundant algae glitter like tiny emeralds in the cold morning sun.

The aquatic weeds are in remission in winter, although they proliferate during the summer months. The seasons affect almost everything about this protected ecological site to the north of Tshwane, except for one thing. The rowers.

It doesn’t matter the time of year, the South African rowing squad can be seen most mornings working out, under the instruction of coaches in motorised boats with loud-hailers. It might look fairly unremarkable to the average passerby, but this stretch of water is a factory belt of Olympic and world championship medallists.

Related article:

Head coach Roger Barrow is the mastermind behind this operation, which is arguably South Africa’s best sports programme. Two Olympic medals and four world championship gongs might not sound like a lot since he took over in 2009, but there’s no other code that has produced that type of bounty with the minimal money and human resources available to them.

Barrow plays many roles at the helm of the squad, starting with ruthless taskmaster. Some years back, two rowers on the fringes of the squad, feeling the first winter chill on the Highveld that season, phoned him early in the morning to ask whether training was still on.

Barrow, in his usual calm baritone, told them off quickly: “Your ex-teammates are training this morning. Don’t bother coming back.”

Rowing at Barrow’s level isn’t for the faint-hearted. It’s a bit like marriage, it demands a long-term commitment from a group of athletes who don’t earn a cent from the sport.

At best, the lucky ones get a stipend from the Operation Excellence funding programme run by the South African Sports Confederation and Olympic Committee (Sascoc). It requires passion and patience. There are times, Barrow admits, when he is almost too scared to ask some of his rowers what their plans are beyond the next Olympics. “The top rowers in the world are in their 30s and they’ve been rowing for years. That’s what we’re up against.”

He’s looking for investments greater than single four-year Olympic cycles. Of the 11 rowers in the senior national squad, four have been with Barrow pretty much since he took over in the wake of the Beijing Olympics in 2008.

A brief history

Rowing already had a proud tradition by the time Barrow took over. The men’s and women’s heavyweight pairs made the six-lane A-finals at the 2000 Sydney Olympics. Then, Helen Fleming and Colleen Orsmond were considered South Africa’s better prospect of a medal than their male counterparts, Ramon Di Clemente and Don Cech. The women, who had competed in Atlanta four years earlier, finished fifth and the men sixth, but it was Di Clemente and Cech who were destined to reach the podium first.

They used to hook up on weekends, Cech driving from Pietermaritzburg to Gauteng to train with Di Clemente. When Paolo Cavalieri, a stalwart in rowing structures who was connected in business, got to hear about this, he organised a sponsorship for the two men in early 2001. The duo went to work for Hollard, getting all the time off they needed to train and compete.

They won South Africa’s first world championship medals as they took minor medals at each of the showpieces in 2001, 2002 and 2003 before landing the country’s first Olympic rowing medal at Athens 2004, a bronze. They won their fourth world championship medal at the 2005 championships.

A seven-year medal drought followed and, in early 2008, Cech was dropped from the boat for young Shaun Keeling. Cech hurt, but the new crew still made the A-final at the Beijing Olympics, finishing fifth.

No room for sentiments

Barrow took over when Di Clemente was the star of the team. Di Clemente and Keeling were sixth at the 2009 world championships and the following year, Di Clemente and Peter Lambert ended seventh overall, winning the B-final. The following year, at the 2011 world championships, which also served as the qualifier for the 2012 Olympics in London, Di Clemente and Lawrence Brittain finished well off the pace in 13th as winners of the C-final.

Di Clemente hadn’t been in top form and that was when Barrow threw sentimentality out the window and dropped the veteran star from the men’s pair boat. It was a difficult move, but Barrow realised he had to do it. He measures the performances of the rowers day in and day out, and he knows who’s performing and who isn’t. Di Clemente’s numbers just didn’t add up.

Di Clemente hurt.

Since then, Barrow has insisted the rowers compete for seats in a boat. This has been his key to success. If rowers are allowed to get complacent, the boat risks going slower. Barrow took Brittain and Keeling to the 2012 Olympic-qualifying regatta in Switzerland, but they ended outside the top two they needed to get to England.

Two South African crews got to London 2012, the women’s pair and the lightweight men’s four. Both those boats had qualified at the world championships the previous year, the women in sixth and the men in 11th. Of the four men in the boat, only three made it to London. James Thompson, Matthew Brittain and John Smith kept their spots, but Anthony Paladin lost out to Sizwe Ndlovu in the final battle for Britain.

Every Olympic year kills careers; those who don’t make it invariably quit the sport. Rowing is brutal, but it can be glorious, too. In London, the South African men edged Great Britain and three-time champions Denmark to land the country’s first Olympic rowing gold. It was a surprise for everyone unfamiliar with Barrow’s squad system, especially the television commentators, who confused South Africa for Australia as they crossed the finish line.

That was also South Africa’s first Olympic gold outside athletics and swimming since the previous Games in London, in 1948, courtesy of boxing. More significantly, that victory gave South Africa its second black Olympic champion after 1996 marathon king, Josia Thugwane.

Related article:

It was a milestone in the country’s sports journey, but somehow it didn’t translate into support. Lotto funding dried up after a three-year boon from 2009 to 2012 and Barrow’s programme was hit hard. There was no money to cover the coaches’ salaries or even petrol to power the boats.

“So we’re using R3 000 a week on petrol,” Barrow commented to other coaches after counting the empty jerry cans at the team’s base at Roodeplaat recently.

Even in 2013, when the cash had dried up, they carried on working. “Training is free,” said Barrow. “If you don’t do the training when you get no funding, then it’s too late.”

Injury forced Matthew Brittain into retirement after 2012 and, with Michael Voerman taking his spot, the boat ended sixth at the 2013 world championships.

The chess master

The money side of things improved when Sascoc stepped in as a sponsor of the rowing programme, although that has been reduced this year. With insufficient competition for seats in the wake of the London success, Barrow abandoned the lightweight fours boat and put Thompson and Smith into the lightweight double sculls. Ndlovu was their main rival.

It was a spectacular gamble, with some saying it would never work. The four boat is sweep oar, where each member rows a single oar. In sculls, they use two oars each. It was a different discipline. But Barrow’s instinct was right. The duo won South Africa’s first world championship gold in 2014, in the process clocking a world best time that still stands nearly five years later.

With the men’s pair of Keeling and Vincent Breet taking bronze, that was the first time the country had won two medals at a single world championships.

There was nearly a third podium finish, but the lightweight women’s double scullers, Ursula Grobler and Kirsty McCann, ended fourth, less than a second short of the bronze medal. They had been in the top three for three-quarters of the race, but fell back over the final 500m.

While Barrow was pushing his senior stars to fresh heights, he had also been grooming the youngsters. In 2010, South Africa won their first Under-23 world championship medals. That year, Smith and Lawrence Brittain kick-started a run of four consecutive men’s pairs medals for the country, taking gold. And McCann took bronze in the lightweight women’s single sculls.

Brittain and David Hunt took silver in 2011 before Hunt and Breet made the podium in 2012 and 2013, taking silver then gold. Breet had won a scholarship to Harvard, studying biomedical engineering, but he put that on hold to come back and try out for the 2016 Olympics. Breet was unseated by Hunt in 2015, who helped qualify the boat with Keeling for the Olympics at the 2015 world championships.

More history

McCann and Grobler made history by becoming the first South African women to make a world championship podium in 2015, taking bronze. Thompson and Smith ended fourth. Lawrence Brittain, who was diagnosed with lymphatic node cancer in late 2014, returned to the sport in 2015 before winning a place in the pair with Keeling for the Olympics.

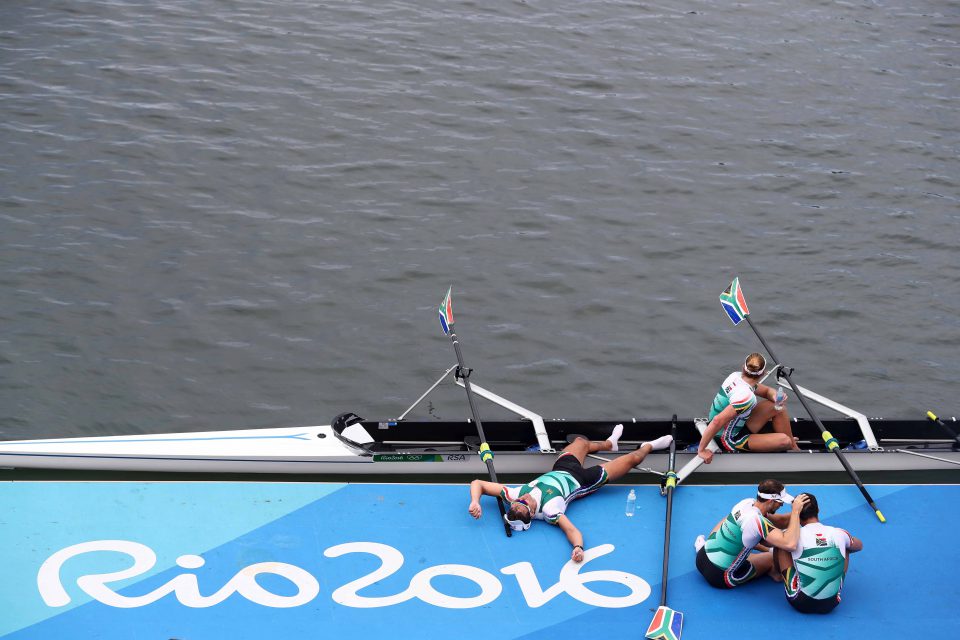

With Hunt, Breet, Jake Green and Jonty Smith pushing hard to make the pair, Barrow had a competitive four that he qualified for Rio. With a women’s pair also qualifying, Barrow had an unprecedented five boats heading to the Olympics. All five boats made A-finals, but only Brittain and Keeling reached the podium, taking silver in the pair. There were two fourth places, a fifth spot and a sixth.

Even so, that was enough to earn Barrow World Rowing’s Coach of the Year. That award and a flood of retirements marked the aftermath of Rio. The departed included Thompson, Jonty Smith, Breet, Lee-Ann Persse, Kate Christowitz and Keeling, who required surgery for a severe ligament injury in one arm.

For once, Barrow was feeling bad. Keeling had complained of a sore elbow frequently during the build-up to Rio. “Yes, Shaun, I know it’s sore,” Barrow had told him. “But really! This is rowing.”

It turned out that the ligament was detached from the arm. “I felt quite bad,” said Barrow.

Rowers are frequently on the edge of injury and illness, and one of Barrow’s masterstrokes was bringing in a palliative care specialist – the mother of the Brittain brothers – to help distinguish between serious injuries and regular pains. But the thing about Barrow is that his no-nonsense approach has shaped the team culture, the rowers have bought into his vision.

Related article:

Olympic qualifying standards have been a debate in the country this decade, with weaker sports saying they should be allowed to qualify on easier standards. Sascoc wants the more difficult options. Barrow and his rowers are on Sascoc’s side on this issue, simply getting to the Games shouldn’t be the goal. You’re either good enough to compete for a medal or you shouldn’t go to the Olympics.

But the coach concedes that excellence takes time to achieve.

“It’s an evolution,” Barrow says. “It certainly doesn’t happen overnight. There are even people in our team who, in their minds, it’s still to get the T-shirt because they haven’t won much. For them to believe in winning is still difficult. You learn to stand on the podium. Once you actually get there and you do it a few times, that becomes the standard.

“But if you’ve never been there, I think it is very difficult. You can’t dream it. Well, you can dream it, but it’s not reality.”

Booking a ticket to Tokyo

Barrow is at the world championships in Ottensheim, Austria looking to qualify three boats for the Tokyo Olympics. Grobler has been competing against Nicole van Wyk, a two-time Under-23 medallist, for the seat alongside McCann in the lightweight women’s double sculls.

Barrow tried switching McCann and Van Wyk around, putting McCann into the stroke seat, but it was an experiment that didn’t work. McCann is back in the bow.

Smith has stepped up to heavyweight and is currently in the pair with Lawrence Brittain. That was also a reshuffle, with Brittain swapping from the bow to the stroke seat. This experiment is still to be tested at international level. Hunt and Green, the sole survivors of the Rio four, are still in the boat alongside Kyle Schoonbee, the 2017 Under-23 single sculls world championship silver medallist, and Sandro Torrente, another youngster.

Qualification for the Olympics has gotten more difficult than it was in the past for two of his three boats – the women must be top seven, instead of top 11 as it was four years ago, and the men’s four must be top eight, instead of 11. The men’s pair remains top 11.

Looking ahead, Barrow turns his harsh outlook inwards. He knows he can’t rely on his past successes. It’s all about what his squad does between now and Tokyo 2020.

“If we don’t qualify any boats, I don’t have a job to do next year.”