ANC factionalism fuels vaccine scepticism

In Joburg’s inner city, existing political fault lines are providing fertile ground for the spread of misinformation, with vaccine scepticism taking hold.

Author:

27 January 2021

As science around the Covid-19 pandemic becomes increasingly contested in South Africa, the consistently trialled efficacy of the vaccines approved so far, to protect against the virus, is encouraging.

But, as debates over the procurement of vaccines – and how they will be transported, stored and distributed – rage on the surface, pockets of organised scepticism that threaten to mutate into resistance are bubbling below it.

Despite their importance in battling the pandemic, it remains unclear what proportion of people in South Africa would be willing to take a vaccine if it were available. As misguided scepticism is mainstreamed (on 15 January, for example, the provincial government in KwaZulu-Natal was forced to organise a public myth-busting event under the title, “Does 5G Cause Covid-19?”), different opinion polls – notoriously imprecise in South Africa – have delivered varying results.

Related article:

In December 2020, an Ipsos World Economic Forum survey suggested that around one in every two people in the country would choose to be vaccinated. A month later, the University of Johannesburg’s Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) Covid-19 Democracy Survey shows that that number is 67% – and that is nearer to the levels required to achieve community immunity.

Among many residents of Johannesburg’s inner city, the misinformation being trafficked on WhatsApp groups appears, as elsewhere, to be cleaving to some of South Africa’s already established and deep political fissures, with ANC factions among the central organising fault lines in the Covid-19 misinformation maelstrom.

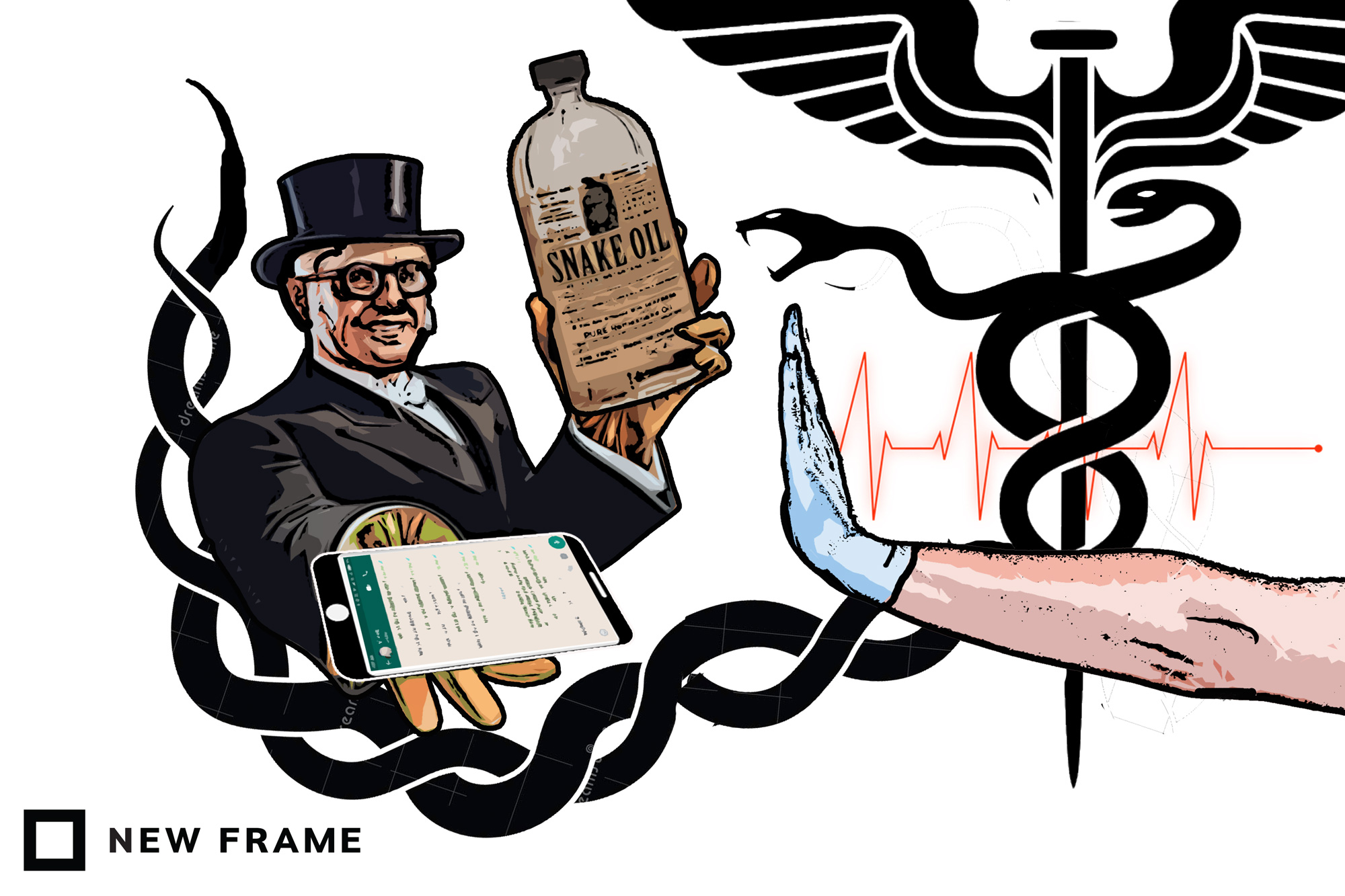

The snake-oil salesmen

The almost constant barrage of misinformation on community WhatsApp groups around the inner city are peddled by figures like Khanyisani Vilakazi, a rapper originally from Lamontville in Durban. After having lived the past 16 years in Yeoville in central Johannesburg, Vilakazi says he is now a “community leader” in the neighbourhood.

Among the daily doses of misinformation regarding the origins of the pandemic and vaccines that Vilakazi distributes to at least seven WhatsApp groups, each with hundreds of members, are the claims that the virus is a long-term United Nations project to “depopulate Africa”. The pandemic – part of a “new world-order agenda” – is a “man-made project,” he says, “to exterminate at least a quarter of Africa’s population.”

The poles now tying together many of the Covid-19 and vaccine conspiracies circulating on Johannesburg’s community groups will be familiar to many.

The one, underpinned by fundamentalist Christian language, was apparently endorsed by Chief Justice Mogoeng Mogoeng. In his now infamous prayer, Mogoeng called for the destruction by fire, “in the name of Jesus”, of vaccines that were the work of the Devil.

Related article:

The other employs pan-Africanist rhetoric to suggest that vaccines constitute a form of neo-colonialism, and that Africa is being left out, or worse, by powers in the Global North. In Vilakazi’s words: “You won’t be able to access the vaccine that will be made for Madonna. No matter how much you claim you have, you won’t be able to access the vaccine that will be made available for Bill Gates and his children.”

This line of reasoning is not new, and resonates with the heights of Aids denialism. Then president Thabo Mbeki correctly identified and rejected a pervasive racism in much of the discourse around the Aids pandemic but, tragically, rejected the science around the aetiology and treatment of the HI virus in conspiratorial terms.

According to Indira Govender, a clinical research fellow at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine based at the Africa Health Research Institute in Somkhele, while Mbeki was justified in pointing out Western pharmaceutical companies’ bloody history on the continent, his eventual denial of science was deadly. “There was this massive denial from the president and his health minister and he gave platforms to quacks. The fact that they were given platforms was a huge part of the problem.”

But amongst the conspiracies, there is a developing common thread which suggests that the vaccine misinformation pushed by Vilakazi and others in Johannesburg’s community groups might be servicing older political divisions.

An ANC member who identifies strongly with the “radical economic transformation” faction of the ruling party, Vilakazi repeats often, both in person and online, that Cyril Ramaphosa and his allies stand to benefit financially from a vaccine roll out. While Bill Gates and other well-established figures in the conspiracy constellation provide Vilakazi with a new grammar, his message is often just one side of long-running ANC factionalism.

Vilakazi, who says that it is his “revolutionary duty” to “safeguard the social interests of the populace”, helped organise and lead numerous community marches and shutdowns against Ramaphosa, both before and during the pandemic.

Confusion and suspicion

Medical historian Rebecca Hodes, who directs the Aids and Society Research Unit at the University of Cape Town’s Centre for Social Science Research, says that, while misgivings about pharmaceutical corporations and their relationships with Africa are understandable, “it is also the case that many medicines are developed and manufactured in Africa, prescribed by African healthcare workers, and used extensively and effectively by African patients.”

Hodes witnessed the dangers of misinformation first-hand during her time with the Treatment Action Campaign, and says there are now clear parallels with the height of the Aids epidemic. “High-ranking political officials sowing confusion and suspicion about the origins, modes of transmission and treatment,” she says, “are parallel cases.”

Related article:

But while “the scope of fake cures and quackery” are also familiar, Hodes remains confident that the ubiquity of mask-wearing is evidence that “people use their logic and common sense in managing their health, and the vast majority of South Africans will use the best means available to them to prevent and treat Covid-19.”

Controlling misinformation will require a good diagnosis of its nature, much the same as with any disease. If the misinformation being circulated among many of Johannesburg’s community groups is anything to go by, an important feature of vaccine scepticism – which will likely not be a bug in South Africa’s effort to reach community immunity, but a feature of it – is that it is cleaving along existing political fissures.

Vaccines will only protect people from getting sick, reduce hospitalisations and the burden of disease, and help to open the economy again if they are taken. But the ways in which conspiracies are being used to furnish and fight deeply entrenched factional politics in Johannesburg’s inner city means that sharing the accurate information required for people to agitate and demand for the life-saving intervention may become even more complicated.

Update, 27 January 2021: This story has been updated to clarify Thabo Mbeki’s Aids denialism with additional comment from Indira Govender.