SA rugby’s racist roots and how to overturn them

Racism is part of the fabric of rugby, whether in the stands, on the pitch or in the boardroom where key decisions are made. But how can the sport rid itself of this to become truly democratic?

Author:

7 October 2020

It didn’t take eight white South African rugby players refusing to take a knee, or former Springbok Ashwin Willemse storming out of a television studio to realise that rugby has a race issue. Race and rugby have been inseparable since the first kickoff and its tentacles reach deep within the game’s structures. Depending on which side of the fence you find yourself, racism is either a tolerable side-effect of change or a crisis that has been overlooked for far too long.

Amplified by the global Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement, former players and coaches, including Willemse, have questioned rugby’s inability to face its racist past and deal with the residual effects of systemic racism. Black players and those classified as coloured by the apartheid regime have long complained of being overlooked for key positions in teams and as coaching staff. The furore over Proteas fastbowler Lungisani Ngidi’s support of BLM seemed to embolden past players to speak out publicly, joining a number of black former Proteas who revealed that they felt victimised during their time in the national team.

So, is it possible for rugby to rid itself of racism? Can the sport exist in a society that has been ravaged by centuries of racial conflict, when racism appears to be institutionalised along with inequality?

Related article:

Rugby, more than most sports, was mollycoddled by the apartheid government. The game did, after all, complete the four pillars that constituted life under orange, white and blue rule; the other pillars being braaivleis, sunny skies and Chevrolet.

Sport was the artificial flavouring that sold the world a mouldy cupcake, while beneath the surface and behind borders it used sport to further deepen the chasm between rich and poor, white and black. Rugby was the slice of life the National Party wanted the world to see, as long as it reinforced the party’s ideals that were passed down by their forefathers.

For more than 150 years, racism has found a willing bedfellow in rugby, as it did with all South African sport and life in general. Over time, rugby became a special brochure for selling Afrikaner nationalism in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. As South Africans grew more divided with each painful twist in a grotesque history of enslavement, statutory or otherwise, black rugby’s light was slowly and systematically dimmed until its heroes died without praise, their dreams strewn by the wayside as unity approached in 1992.

Rugby’s long dance with racism

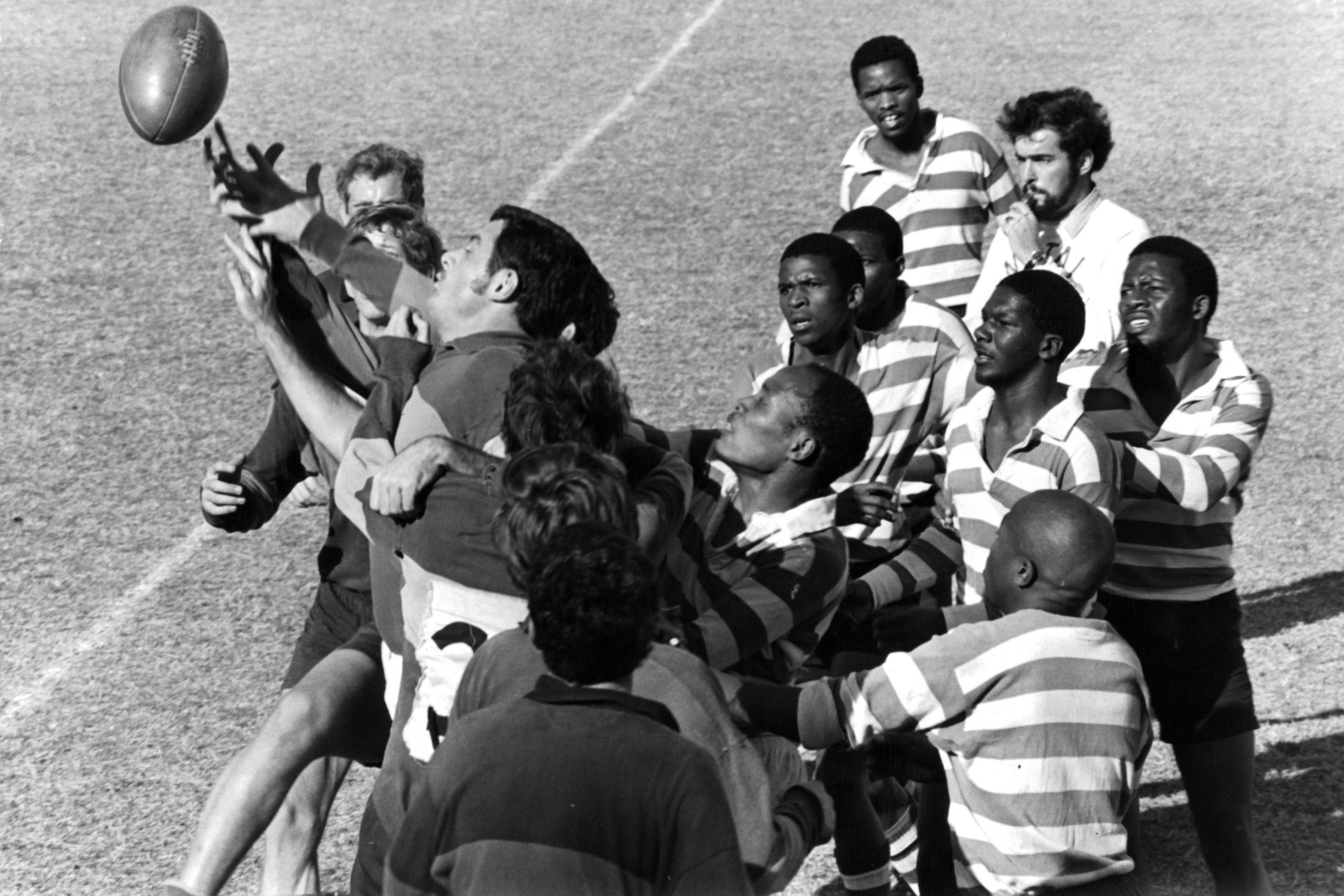

The first rugby game in South Africa was held in 1862 in Green Point, between the army and civil service. It was arranged by the headmaster of Bishop’s College, Canon George Ogilvie. There was just one problem, only white players were allowed to participate. And so began rugby’s dance with racism.

The sport was quickly adopted by white farmers in Stellenbosch and before long, the narrative of rugby as a white sport had been solidified, despite all evidence to the contrary. Rugby’s roots and popularity among African communities were whitewashed, and at times actively subverted under the jackboot of the apartheid regime. The weight and pressure of those jackboots on black communities may have lifted since 1994, but the telltale signs of years of abuse are still plainly evident today.

Related article:

Mark Fredericks is a scholar of sport’s tangles with changing political systems and political environments. He’s a former sports activist from the South African Council on Sport (Sacos) era and lectures in the photojournalism department at Walter Sisulu University in the Eastern Cape. Fredericks has published works and documented research at the nexus of sport, politics and the anti-apartheid struggle.

“We come from institutionalised as well as constitutional and legislated racism. Racism as legislation didn’t start with the Nationalist Party, it was refined by the Nationalist Party. When they took over in 1948, they had these ideas already set out,” he says.

Fredericks spends much of his time highlighting inequality and racism in rugby, from its origins in South Africa to the time the country was banned from participating in international sport. A ban which, according to Fredericks, should have been prolonged until South African sport had gone some way in rectifying the wrongs of its racist past.

The result of rugby’s sordid entanglements with race politics has been systemic inequality that has eroded playing careers for decades and rendered the sporting aspirations of millions of black sportsmen and women stillborn.

Sport under the current circumstances, says Fredericks, has helped legitimise a social system by the very people it is oppressing. “We’ve used sport in such a way that it has made people enthusiastic about the very system that they are now saying is racist,” Fredericks explains.

“We’ve almost come full circle, from the warning that many in the struggle gave to the ANC in the late 1980s, leading up to sporting unity, that we should not have been lifting the sports boycott so early. I mean, Clive Rice took a team to India in 1991. Nelson Mandela sat in the stands in 1992 in Barcelona. He couldn’t even vote in the country the team was representing at the time.”

Sport to unite a divided nation

Sport became a vital pillar of Mandela and the ANC’s democratic project after his release from prison in 1990. It was to be the catalyst to unite South Africans irrespective of race. The lasting effects of that euphoria were meant to inspire a period of nation-building and miraculously steer the country to safety and prosperity.

Triumphs in the 1995 Rugby World Cup, the Africa Cup of Nations a year later, and the hosting of the 2010 Fifa World Cup seemed to fuel belief that a nation’s fortunes could sit comfortably within – or even be derived from – its sporting dreams; overlooking pesky details such as policy negotiations, foreign investment, competent governance, hard work and an actionable plan.

In an interview earlier this year, Fredericks put it this way. “These sports events have taken precedence over the development of essential social structures and services for poor communities in South Africa. Sport is just a way through which South Africans can celebrate something while ignoring horrific social conditions,” he said.

Related article:

But is the inequality we see in rugby simply a reflection of the communities in which the game is found, or is rugby inherently racist in nature – and aided by a skewed system of reward?

In the first year of mother body SA Rugby’s refocused Strategic Transformation Development Plan 2030, it succeeded in 38 of its 47 pinpointed areas, including access, demographics and empowerment.

SA Rugby said the number of rugby-playing schools and clubs exceeded its targets, and demographic targets for black players were achieved in eight out of nine national teams. In addition, 16 of 18 targets were achieved in coaching, refereeing, team support staff, board members and SA Rugby staff.

“The nine areas in which SA Rugby was short of its targets were in black sports psychologists; failing to field either an Under-18 women’s national team or Under-16/Under-17 men’s national teams and at the senior male national level, where the target for black African representation was achieved but generic black representation was at 38% to a target of 45%,” SA Rugby said.

One of the men at the centre of “the system” in rugby in the Western Cape is Danny Jones, general manager of amateur rugby within the Western Province Rugby Football Union. The former principal has served the game of rugby as a player for City Park and Perseverance, and now as an administrator. He represented the City and Suburban Rugby Football Union, a non-racial affiliate of the SA Coloured Rugby Football Board and South African Rugby Union.

Socially engineering apartheid’s effects

Jones is responsible for rugby development in the Western Cape as it relates to schools and clubs in the province. It is a region blessed with natural talent and it is Jones’ responsibility to ensure that the road to rugby success for any boy or girl in the system is as smooth as possible.

His assessment of rugby development and the game’s historic role in society is a far more positive one than Fredericks’. “Look, it’s working. There’s no doubt. The two issues of development are quantity and quality. How do you grow the game? Through your schools. The youth club system and the schools system have a historical background. During apartheid, black schools played during the week, and over weekends you would join a youth club. On the other side of the railway line, the development there was predominantly through the schooling system. In 1995 we married the two, so no community loses out,” Jones says.

But does that translate into more black players in the system? “Yes, if you look at the amount of quality players coming through from all communities, most certainly, it is working. We have over 100 clubs playing rugby and those clubs are important social entities within their communities,” Jones enthuses.

“All provinces had to sign a transformation plan that by 2030, 60% of all teams will be transformed to reflect black players. Apartheid was socially engineered. If you want change to happen, you have to socially engineer change, you can’t leave it to chance,” Jones says.

“The transformation plan is part of that reengineering, so we can get to the point where the access route of players of colour that was denied them before is changed so that all communities can participate in the rugby economy. We can’t deny the impact of apartheid and inequality in wealth distribution and income distribution. The challenges that exist within our poorer communities, even government can’t resolve. If Siya Kolisi had stayed in his school in Zwide, he might not have played for Grey High School in PE or played for the Eastern Province schools team. It was easier to get to a higher level.”

Related article:

Wealthy schools are not just aligned to the province’s developmental stream, they are vital tributaries in the entire ecosystem, even though, as critics point out, the high fees make access to such schools exclusionary based on socioeconomic standing.

“Your more affluent schools do contribute to the quality of rugby by developing players, including players from poorer communities by offering bursaries. We do piggyback off that. For some of our development programmes, we don’t include boys from SACS, Wynberg and Bishop’s. They fulfil one component of our pipeline, so we can concentrate on the others,” Jones adds.

Bishop’s College, through headmaster Ogilvie, played a vital role in the staging of the whites-only first official game of rugby mentioned earlier.

“Our society is not equal, and we have to deal with societal inequalities that exist in our communities. Part of our challenge is getting the rough diamonds and making them better so they can display their skills at various levels. Development programmes need financial investment in growing our rugby population and improving the skills of our players. Rugby is a professional occupation, so it does offer a few kids the opportunity to play rugby professionally,” the veteran administrator admits.

How to fix rugby’s race problem

So if rugby today is more unequal than it is racist, and the inequality is based on racist ideology and policies, how does the sport rid itself of such poison?

“In an ideal world, we would like to develop every rugby player to the level where he can play for the Stormers. But the model of professional sport doesn’t necessarily lend itself to that. We do our best to develop kids at age-group level and we hope that when they are at that post-matric and university level, that their further development takes place and scouts scoop them up,” Jones says.

Wilbur Kraak is a rugby coach who has seen and experienced the cold shoulder of rejection within the rugby fraternity. He grew up in Mamre, about 50km west of Cape Town, a town that prides itself on running rugby and has produced many top-class players in a variety of sports.

Kraak is a senior lecturer of sport science at Stellenbosch University and is studying towards a second doctorate in sports coaching through Cardiff Metropolitan University in Wales. He’s coached at every level in rugby, from schools and clubs to provincial, and is consulting with the Nigerian national rugby team.

As a black coach, Kraak has been on the wrong side of decisions made about his rugby coaching career more times than he can remember. Tired of being overlooked and undervalued, rugby’s race issues have pushed Kraak to the forefront of the movement of black players and coaches who want to see racial equality in rugby in their lifetime. The movement has aligned itself to the BLM movement, and supported Ngidi’s BLM stance.

Related article:

“When 1992 came, everyone thought great, we’re back in the international fold and unity would come. That didn’t happen, that’s a reality. One of the reasons is that SA Rugby decided that one part of history would continue, white rugby. But black and so-called coloured rugby was pushed aside. After unity we should have started from scratch, so that we all start from the same level. People still believe that rugby belongs to one race group. We’re not part of that and that’s what’s causing the divide. When we first wanted to unite, we didn’t first unify our minds, and transform our minds and get a sense for what it means,” Kraak says.

He leads a movement of more than 50 black coaches, administrators and service providers who say they continue to be excluded as head coaches, directors of rugby, high-performance managers, chief executives or providers of professional expertise.

The players and coaches complained about being marginalised for speaking out against racial inequalities in sport. “It is this fear of losing employment and being left without a plan B that is making the number of people on this list a little less than anticipated. We can no longer live in fear and our inner voices won’t be silenced anymore. From the time of colonialism into apartheid, there has been uninterrupted ‘white’ control of the top coaching and administrative posts,” said the movement.

It’s an issue that Jones insists can be overcome, and that rugby is trying to correct itself. Jones says the system is changing. “Most certainly. If you look at how Eben Etzebeth kissed Bongi Mbonambi on the forehead when we won the World Cup. That action speaks volumes. When you run on to the rugby field that player next to you is your brother, who’s going to have to defend you and you’re going to defend him,” he says. “On the field, there’s no time to think about who is a black player and who is a white player. You need each other to win a game. Yes, conflict is happening. Some areas are better than others. There is systemic racism in our society and this is why we are saying BLM is important.”

For Fredericks, it runs deeper than the BLM movement and that the fight against racism in rugby begins on the sidelines, in the game’s boardrooms and in the communities rugby serves.

“If we really want to ask the question about structural racism in rugby, we have to be honest and ask if it is possible to have racism within that structure of society or institution and not have it in society itself,” Fredericks says. “How is it possible that a non-racial society would allow racism to exist in one of its institutions? It’s impossible. The fact of the matter is we have a racist society.”

This is part of a series of articles looking at racism in SA rugby.