SA faces slow economic recovery prospects

The government’s proposed stimulus packages are insufficient to deal with the challenges the country faces. It will take a dramatic shift in approach to avoid another dire decade.

Author:

25 August 2021

After experiencing the deepest contraction in a century during 2020, South Africa faces a painfully slow recovery that will result in a second lost decade in the years to 2030 unless the government substantially changes its failed economic policies.

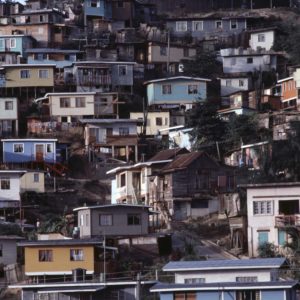

The inevitable outcome of the state’s neoliberal policies – capitalism on steroids, by another name – is a further increase in unemployment, poverty and inequality. This will push an already unviable society in which half of Africans do not participate in the economy to the edge, resulting in repeat episodes of the social unrest, violence and eventually repression that we saw in July.

The crisis after the financial crisis saw existing public healthcare, humanitarian and economic issues collide – and the government botched its response. By 15 August, there were 2.6 million Covid-19 infections, 77 141 official deaths and 229 850 excess deaths among South Africa’s 60 million people. South Korea with 51.2 million people had 225 481 infections and 2 167 deaths, with no national lockdown.

Related article:

Business Day newspaper editor Lukanyo Mnyanda called for a commission “to establish how South Africa came to have one of the most severe lockdowns in the world and still emerged with one of the highest death rates anywhere in the world”.

The National Income Dynamics Study – Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey reported that 10 million people and three million children were living in a household affected by hunger in April and May 2021. Unemployment rates during the first quarter of this year were at 74.7% for the youth, 47.9% for Africans, 51.5% for African women, and 49.5% in Limpopo and 49.6% in the Eastern Cape, according to Statistics South Africa’s labour force survey for the quarter.

At the start of 2021, analysts expected the economy to experience a technical rebound from the low base in 2020, primarily because there could not be another lockdown as severe as the government’s initial stringent lockdown. The economy would then revert to its pre-pandemic trend of low GDP growth in the following years. The risk to the 2021 outlook was the likelihood of further waves of the pandemic, because of a then non-existent vaccination strategy and the government’s failure to contain the virus as many countries in East Asia and others such as Australia and New Zealand had done.

Related article:

Since then, the battered South African economy has suffered repeated blows. It will again underperform when compared with the world economy, which will grow by 6% in 2021. Emerging and developing countries in Asia will grow by 7.5%. China and India will grow by 8.1% and 9.5% respectively, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

But the IMF, previously a cheerleader for austerity, now advises against it. “It will be critical for countries not to withdraw support prematurely and, importantly, to continue to target the measures in a way that helps the most vulnerable,” says managing director Kristalina Georgieva. And IMF economists Marcos Chamon and Jonathan Ostry write that “countries should not run larger budget surpluses to bring down the debt, but should instead allow growth to bring down debt-to-GDP ratios organically”.

The government ended its Covid-19 social relief of distress grant in April, which had paid six million people R350 a month. The country then experienced brutal cuts to power and water supply in the middle of winter. A report by the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research found that Eskom had its worst year of load shedding on record in 2020, with 859 hours of scheduled power cuts. But there were 650 hours of scheduled cuts in the first half of 2021, equivalent to 75.6% of the 2020 total, meaning 2021 is likely to surpass last year’s record.

Elusive neoliberal gains

President Cyril Ramaphosa began his road show in June to launch the structural reforms that are part of the government’s economic reconstruction and recovery plan. Within this, the government talks about an infrastructure-led recovery. But it has committed only R4 billion in 2021-2022 towards the R100 billion infrastructure fund it announced two years ago. The absurd idea is that the private sector will finance the entire recovery. The financialisation of public infrastructure is not viable in a country where so many people are impoverished and whose government will not pay the huge subsidies that are required to de-risk such projects and guarantee high returns.

The other pillar of the recovery plan is Operation Vulindlela, an initiative to implement structural reforms outlined in the treasury’s economic strategy in October 2019. Structural reform is code for privatisation, deregulation, liberalisation and the withdrawal of the state from network industries: electricity, transport, telecommunications and water. It refers to measures to improve the supply (or production) side of the economy by removing institutional and regulatory impediments to the functioning of free markets.

Related article:

Harvard economist Dani Rodrik says gains from such neoliberal reforms since the 1980s have been elusive. “The experience suggests that structural reform yields growth only over the long term, at best. More often than not the short-term effects are negative.” The IMF says “most reforms are likely to only make a small near-term contribution to ongoing recovery, as it takes time for the gains to materialise”. The treasury’s economic strategy said the benefits from its proposed reforms were marginal and would take many years to materialise.

Structural reforms will not address any of South Africa’s immediate humanitarian and economic crises. Tackling the supply side of the economy when the average large factory had spare capacity of 21.4% in May will only result in more idle machines. The economy needs more aggregate demand or spending power. Economist Ilan Strauss says talk of structural reform in the midst of a recession is like telling an intensive-care patient who needs a life-saving intervention about the need to exercise and maintain a healthy diet.

In the energy sector, Ramaphosa increased the licensing threshold for embedded power-generation projects to 100MW. The announcement was no game-changer. It is expected to create investment of R75 billion and new power capacity of 5 000MW between 2022 and 2024. That is equivalent to only 0.5% of GDP a year. The liberalisation will not tackle the immediate crisis of power cuts. It will accelerate Eskom’s death spiral as the utility loses key customers and needs more financial bailouts.

It will result in an increase in energy inequality. There will be two energy systems – one for wealthier households and a few large companies that exit the grid and have power 24/7, and another for the millions of South Africans who continue to rely on Eskom. The government also announced the privatisation of South African Airways and the establishment of the National Ports Authority as an independent subsidiary of Transnet.

GDP forecasts

Ramaphosa announced an intense lockdown on 27 June to contain the third wave of the pandemic, but failed to allocate a cent to the millions of people who would be affected. During the second week of July, South Africa experienced its worst social unrest since 1994, with unprecedented scenes of looting and violence in KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng that resulted in 342 deaths. The South African Property Owners Association said the unrest had a R50 billion impact on GDP.

At the end of July, then minister of finance Tito Mboweni announced a R36 billion stimulus package equivalent to 0.7% of GDP. It included R26.7 billion for the reintroduction of the Covid-19 social relief of distress grant until March 2022; R3.9 billion in support of Sasria, a state-owned provider of special risk cover, including riots; and R2.3 billion in financial assistance for businesses not covered by Sasria.

The stimulus, which is inadequate compared with the scale of the crisis, will be financed from the government’s excess cash from a tax windfall as a result of higher commodity prices. It will cancel the planned austerity measures of R27 billion for 2021-2022.

Related article:

The government had cash of R292 billion at the end of the fiscal year in March. Tax revenues in 2020-2021 were R137 billion higher than the estimate in the October 2020 medium-term budget policy statement. With commodity prices holding up, despite retreating from recent highs, most analysts expect the treasury to have excess cash of more than R100 billion in this fiscal year.

Economists are divided on their GDP forecasts for 2021. After modelling the effect of the power cuts, lockdown and social unrest, accounting firm PwC has reduced its GDP growth forecast to 2.3% from 3.7%

Other economists say a better than expected GDP performance during the first quarter of 2021 and a strong rebound effect will counter the recent blows to the economy. Nedbank and Absa have forecast GDP growth of 4.2% and 4% respectively.

Whatever the outcome for 2021, there is agreement that GDP growth will return to its pre-pandemic trend in coming years. The treasury says the economy will return to the 2019 level of GDP in 2023. If one takes into account population growth, it could take until 2025 for GDP per capita to return to this level.

Three outlooks for SA

The Indlulamithi initiative presents three scenarios for the economy until 2030. In the trickle-down iSbhujwa outlook, the government continues with its 1996 policy framework and sees average GDP growth of 2.2% a year to 2030. In the impoverishing Gwara Gwara outlook, the government also implements austerity policies – as it has done in the budget – producing an average GDP growth of 1.8% a year to 2030, which is barely higher than the country’s population growth rate.

The pro-impoverished Nayi le Walk outlook requires a shift from the status quo. In this scenario, the government implements a six-pillar policy framework that includes bold macroeconomic and social policy reforms. The Reserve Bank changes its mandate to target inflation and a 6% GDP growth rate. The government introduces a new grant of R1 000 a month for unemployed, skilled people and makes the public works programme an employer of last resort, paying a daily wage of R160 for unskilled people who do not have work.

In this scenario, there is GDP growth of 6.2% a year to 2030. The economy creates between 8.7 million and 10 million jobs, and the official unemployment rate declines to 12%. The poverty rate halves to 23%.

Minister of Finance Enoch Godongwana has two choices. If he continues with the status quo of austerity and recycled plans for infrastructure and structural reforms that were developed long before the crisis, South Africa will lose a second decade. If he ditches the failed economic policies, he could lead the country on to a new path of lower unemployment, poverty and inequality.