Roti makes the world go round

A staple food in households in India, the flatbread has made its way to regions and cultures across the globe, where it is enjoyed in all its lip-smacking varieties.

Author:

2 September 2021

I learnt to make perfectly round rotis when I was young. My maternal grandmother taught me to use a trick of the hand to get it right every time. Until recently, I was oblivious to the fact that the ability to create round rotis was seen by some as a desirable quality, marriage material, even.

Roti has many names. Also known as chapati, safati, shabaati and roshi, the unleavened wheat flatbread cooked on a hot tava, or griddle pan, is familiar in some form or another around the world. While it is often assumed to have originated in India, wheat was first grown in the Levant in the eastern Mediterranean region of western Asia.

A bread recipe resembling a chapati was found in Jordan dating back to 14 000 BCE. Wheat arrived in India in 6 500 BCE and it is said that chapati was mentioned in a 6 000-year-old Sanskrit text. While these are speculations, it is certain that roti has been a staple part of the Indian diet since the 1600s, first developing in the north of the country before spreading to the south. Today, roti is associated with multiple distinct and connected food cultures around the world, from Asia to Africa and the Caribbean.

Food has the ability to transcend differences in a world that is profoundly polarised and divided. “The power of food can make two different cultures and communities become one. Roti is now so deep in many African and Caribbean cultures that it’s become a Black food. It is a new food world,” says Coralie Kory, a vegan chef and the owner of plant-based restaurants Le Tricycle and Jah Jah Cafe in Paris.

Today, in its movement across history and place, roti can be enjoyed as a traditional dish or, as Kory loves to have it, with “veggie curries, plantain, spinach, sweet potato, mango or tamarind chutneys, green mango achar and hot pepper sauce”.

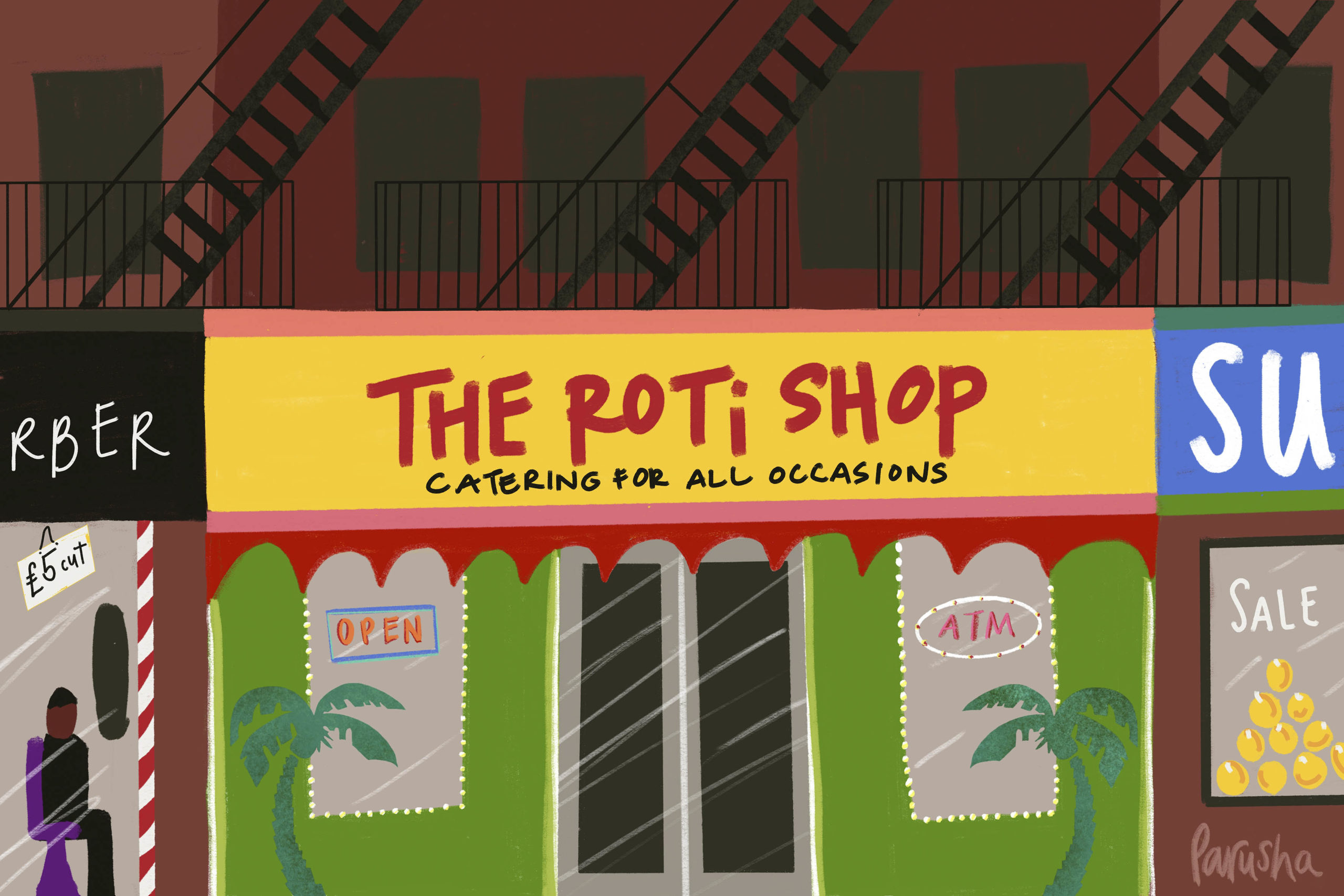

Wherever Indo-Caribbean populations venture – from London to New York – the institution of the roti shop, a phenomenon first seen in Trinidad and Tobago in the 1940s, has exploded. In the Caribbean, the roti refers to the “skin” wrapped around a curry filling. There, the two flatbread varieties are dal puri (a roti with a layer of ground split peas in the middle) and “buss up shut” (a large, layered, flaky, buttery flatbread similar to Indian paratha).

Popular in the Caribbean and Mauritius, dal puri has a fascinating history. While it became a street food in both these regions, to where indentured labourers from Bihar a state in East India were sent, in India it is only eaten in homes.

The roti shop, a fast-food establishment where it is sold as a portable bundle, developed outside of India. In South Africa, takeaway roti rolls can be found in curry houses and takeaway shops specialising in bunny chows or Gatsbys. In Durban and Cape Town, Sunrise Chip ’n Ranch (open from sunrise to sunrise and also known as Johnny’s rotis) serves the biggest roti in South Africa – a chip and cheese roti that can feed two or three people. The roti itself is more of a secondary item than a main feature. They started selling bunny chows at cheap prices. In India, the portable rotis with fillings are called Frankies. The roti shops where roti is the main commodity seems to be mostly a Caribbean creation.

What’s in a name

“Across the east coast – Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania – roti or chapati is regarded as African,” says Bobby Marie, a South African activist and home cook. What is known as paratha in India is the recipe behind the roti of the Caribbean and chapati of east Africa.

In South Africa, the Cape Muslims also have a paratha-like roti, sometimes called a rooti. The filled and wrapped version is known as a salomie in Cape Town. One of the many theories about the origins of roti is that it was created in East Africa and introduced to India. As there was mutual trade between Asian and African countries along the Indian Ocean predating European settlers from the eighth century, this is a possibility.

Related article:

In South Africa, Marie says, roti was used as a way to divide Durban’s Indian community when he was growing up in the 1960s and 1970s. In the city, the descendants of indentured labourers were divided along language lines.

“When I hear the word roti, it goes with ‘roti people’. All Hindi speakers in our community in Merebank in Durban were referred to as ‘roti ous [guys]’. In turn, we were called ‘porridge ous’,” he says – a reference to the annual “porridge prayers” to the Hindu goddess Mariamman. “This was not simply a casual reference. The difference was to keep the porridge ous from messing with the roti girls and vice versa.

“There were some ugly incidents when people crossed this line, pointing to roti being a serious dividing line, though now the line has begun to blur with the food divisions in the Durban Indian community. In the larger South African community, I think there is an Africanising of Indian food.”

A bread for every culture

“There is something so instinctive about eating with your hands,” says Lelani Lewis, a chef, culinary activist and the owner of Nyam, a catering company and roaming restaurant in Amsterdam showcasing the diversity of Carribean food. “You use the bread to mop up the curry, the meat and the sauce. I think of roti as a food associated with people of colour. I am a fan of flatbreads generally and love the fact that every culture has an unleavened bread. It’s tasty and interesting to see the variations through the regions.”

There are many almost identical or similar flatbreads to roti or chapati in the world. Mexican flour tortilla, Levantine taboon, Yemeni malawach, Turkish lavash, Iraqi laffe, Somali sabaayad and msemen of Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco. The similarities between them are greater than their differences.

Wheat made its way to Mexico via the Spanish, who were colonised by Muslims until the late 1400s, connecting Spain to North Africa, the Persian Gulf and India. While distant on a map, Mexico is easily linked to India via trade and conquest.

“Having something like a roti, a flatbread, and considering it a food that we all have is a beautiful way of connecting our humanity. We not only use food as sustenance, but as a way to evoke memories and connect to each other,” says Lewis.

The chef is a believer in food’s ability to bring about positive change. “Food can bring us together to sit at a table no matter the differences,” she says. “Everyone can enjoy a meal together whether we speak the same language, or have the same religion or beliefs. We can all sit together and have the commonality of the enjoyment of that meal.”

In this sense, food, not just roti, has the special and unique power to unify people. “The fact that roti was brought to the Caribbean by the Indian indentured labourers makes you think that it’s not just unifying people, but unifying cultures.”