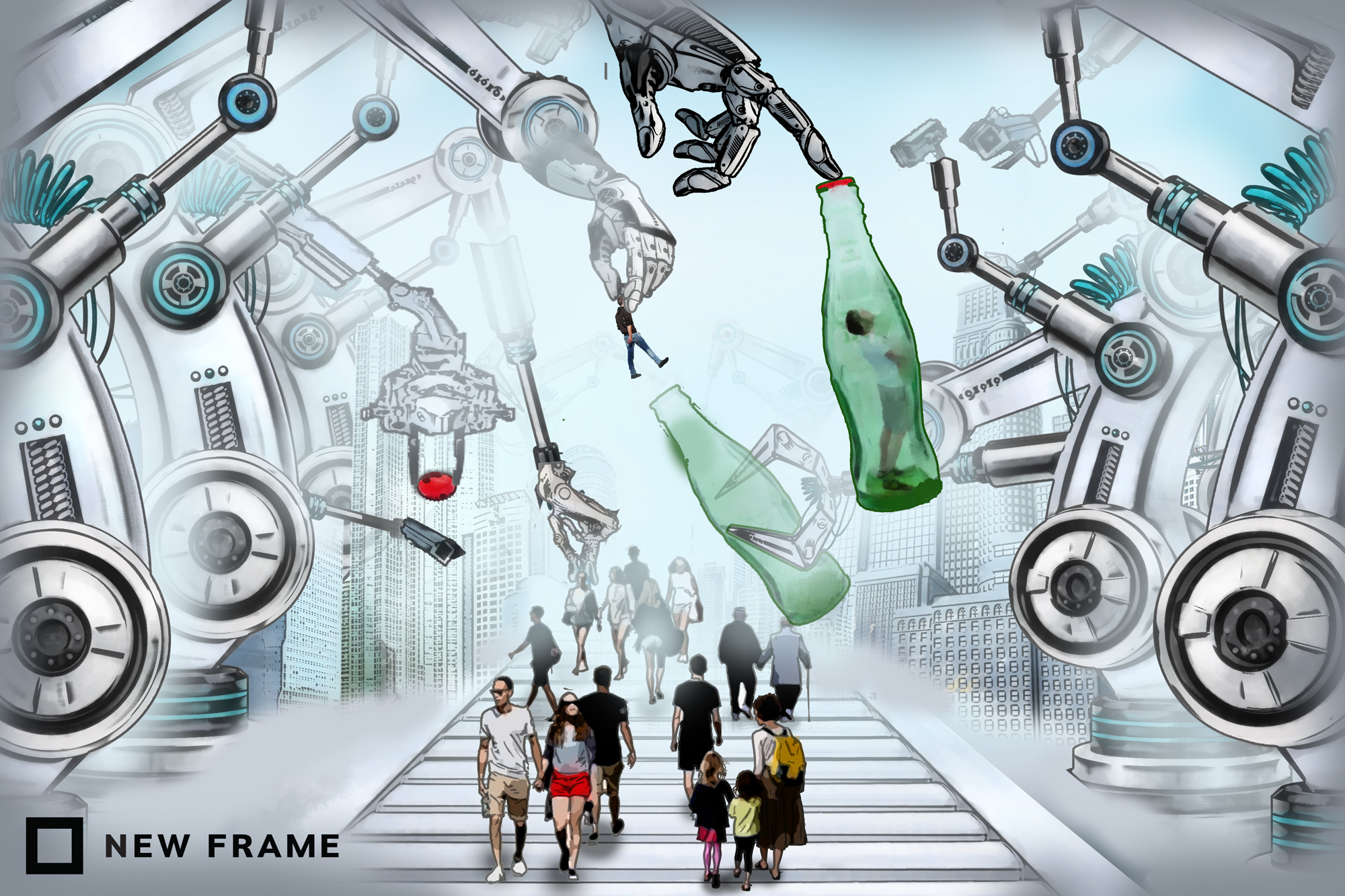

Robots will put people out of work – and hope

The fourth industrial revolution – in which most repetitive or labour-intensive tasks are automated – has the potential to unravel the social contract.

Author:

9 November 2020

A recent global news story highlighted a three-year partnership between Fieldwork Robotics and French canned vegetable producer Bonduelle to develop a cauliflower-picking robot. Bonduelle operates across more than 100 countries, while Fieldwork Robotics was cofounded by Martin Stoelen, a lecturer in robotics at the University of Plymouth.

Fieldwork Robotics has already collaborated with one of the United Kingdom’s biggest soft-fruit producers, Hall Hunter Partnership, to develop a raspberry-harvesting robot.

If you type “vegetable harvesting robot” or “fruit harvesting robot” into a search engine, you will discover that Fieldwork Robotics is no mere anomaly. From Japan to Spain, inventors are ploughing the field of harvest robotics.

This is worrying considering 60% of total employment across Africa is in the agricultural sector and that even more people have suffered hunger or starvation during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Related article:

Tshilidzi Marwala says robots are more reliable than humans, simply because they don’t get sick. “If the worker is a robot, it doesn’t have to social distance,” he says.

Marwala is the vice-chancellor and principal of the University of Johannesburg (UJ) and the deputy chair of the South African presidential commission on the fourth industrial revolution. He is also the author of a new book, Closing the Gap: The Fourth Industrial Revolution in Africa.

This new revolution is driven by technological developments such as artificial intelligence, big data, cloud computing, robotics and the internet of things. While it is still at the early stages of development, it is already affecting our lives.

Digital workers

In September this year, MTN’s global sourcing and supply chain division hosted a live webinar on procurement digitalisation in a post-pandemic world. The webinar introduced MTN’s artificial intelligence assistant, GeSSiCa, and its decision support application. (GeSSiCa is derived from Global Sourcing and Supply Chain, GSSC.)

GeSSiCA is an example of robotic process automation, often referred to as software robotics. According to MTN, GeSSiCa has been put to work, automating time-consuming, administrative and repetitive tasks within its supply chain management division.

MTN says this frees supply chain staff to focus on strategic procurement and better decision-making based on accurate data. GeSSiCA is essentially a digital worker for the fourth industrial revolution.

“The Covid-19 pandemic has compelled us to work remotely and rely even more on technology than ever before,” says MTN group executive for procurement and supply chain management Dirk Karl. “Developed entirely in-house, GeSSiCa – our artificial intelligence assistant – and our decision support application [focus] on improving business efficiency and enhancing fact-based decision making.”

In an evolving world that is seeing the introduction of cauliflower-picking robots and digital assistants, the question is, what does this mean for the worker?

Future jobs

In 2018, the World Economic Forum released its Future of Jobs report. At the time, the report stated that 71% of all work tasks in the global economy were performed by humans. The other 29% were being performed by machines.

The report predicted that by 2022, humans would be performing only 58% of all tasks. So what happens to the workers ousted by machines in less than two years?

Future of Jobs says some predictions indicate that up to 75 million jobs globally could be displaced, but there are also predictions that these displaced jobs will be offset by new ones created through the fourth industrial revolution, resulting in a net gain in jobs for the global economy. What is certain is that the labour market is facing a severe shake up – and it’s already under way.

Related article:

In the report Notes from the AI Frontier (2018), the McKinsey Global Institute modelled the effect of artificial intelligence on the global economy. It predicted work that could be classified as repetitive would decline to 30% of the global wage bill, down from 40% at the time.

McKinsey forecast this would correlate with an increase in work that could be classified as social or cognitive, which would grow from 40% of the global wage bill to 50%. Notes from the AI Frontier suggests this will mean a cut or stagnation in wages for workers who perform repetitive tasks and a rise in wages for workers involved in social or cognitive work.

Post-work

Tshikululu Social Investments’ Riyaadh Ebrahim argues that Covid-19 has shown us both the possibilities and the challenges of the transition to the fourth industrial revolution. He says with companies embracing their employees working from home during the pandemic and investing in technology, what might have taken 10 years to achieve happened in a few months.

On the other hand, he argues that workers earning a living in the gig economy, such as Uber drivers or Airbnb owners, were left floundering by the effects of the pandemic. “Gig economy workers were severely impacted because they have no income protection,” says Ebrahim.

Marwala agrees that the Covid-19 pandemic has “accelerated” the world into the fourth industrial revolution. “If you had come to UJ last year and asked, ‘What is Teams software? What is Zoom?’, not many people would have known,” he says. “Behind those technologies is artificial intelligence (AI) – when you select a virtual background, the software is being aided by AI to match your face to the background.”

Related article:

Marwala defines the fourth industrial revolution as a “post-work” one, where the need for humans in the workforce “will be severely curtailed, effectively changing the face of labour”.

Ebrahim agrees, arguing the effect on the workforce will be “tremendous”, as a lot of repetitive types of work will be transferred to new technologies.

He points to human resources (HR) bots, which already exist. He argues that these bots can be installed in an HR office so it can monitor the human HR worker handling basic email administration tasks. “Once the bot has monitored 1 000 responses by the human, it can begin generating email replies to queries,” he says. “Within 10 000 responses, it can take over the basic HR admin completely.”

Unravelling the social contract

In Closing The Gap, Marwala writes that South Africa’s participation in this revolution will not be optional. “Either we participate, or as a country we are economically obliterated, relegated to the ‘dustbin of history’,” he writes.

“Those who adopt the means of production of the [fourth industrial revolution] will produce goods at such low costs that the price of products will fall sharply,” he writes. “Those who refuse to use AI robots to run their factories will be so uncompetitive in price that no one will buy their goods, and they will ultimately be put out of business by market forces.”

Congress of South African Trade Union’s parliamentary coordinator Matthew Parks agrees that not preparing as a country will be “condemning yourself to oblivion”. “The fourth industrial revolution is going to happen whether we like it or not,” he says. “It’s going to turn everything upside down for better [or] worse. There are going to be huge amounts of job losses. Some sectors will be completely obliterated.”

Parks mentions a recent visit to a Chinese port in Qingdao that was fully automated. “There are only a handful of workers sitting in control towers,” he says. “The port works 24/7, and they don’t even need to put on lights at night, because computers don’t need to see.”

Related article:

A 2018 Accenture study estimated that 6 million South African jobs could be lost to automation by 2025. Marwala points out that robots, unlike human workers, will not be organised by trade unions.

“To paraphrase Karl Marx, AI robots cannot be mobilised by the cry: ‘AI robots of the world unite! You have nothing to lose but your chains’,” he writes. “Those with financial capital will simply buy AI robots and produce goods and services to maximise profit.”

But Marwala argues that South Africa’s labour market is structured around unions.

“From where I’m seated, the union is an instrument of the industrial age,” he says. “But as we move into the [fourth industrial revolution] the big issues will not be the same. The big issue will be human irrelevance.”

Unions can’t represent unemployed citizens, so new formations will have to rise up to address the concerns of those without work. Parks says that every worker supports approximately seven unemployed relatives, so to argue that unions only represent the interest of workers is not completely true.

Parks also admits that it is not a new phenomenon that jobs become redundant, pointing out that in the 1800s a person was employed to walk through the street ringing a bell to wake people up in the morning, and in the 1980s in South Africa, we used to have people who delivered milk.

But he says low-skilled workers who will battle to find employment in the fourth industrial revolution need to be reskilled. “A just transition can’t just be a warm fuzzy word in the sky,” he says. “Money is available in government to retrain workers. It’s not being tapped into. Our whole skills system is a joke. We have to get our act together.”

Related article:

Marwala adds that the “social consequences” of the revolution will be “extensive”, and South Africa cannot afford to wait till there are “massive dislocations in our society” to prepare for it.

“[The fourth industrial revolution] is going to unravel the social contract,” says Marwala. “The Gini coefficient, which is a measure of inequality in society, will increase, threatening the very existence of the notion of a nation state.

“Now more than ever, there is a need for a country to wisely invest in technological revolutions as well as its citizens. What is definitely required is reimagining our education system to offer continuous training and reskilling.”

Effect on South Africa

The Future of Jobs suggests that 23% of South African workers will require reskilling that could take up to three months to be employable in the future; 29% will require from three months to over a year of reskilling; and 47% of workers will require no reskilling. With over half the workforce in need of reskilling, it is important to think about how this will take place and who pays for it.

A 2018 Deloitte report titled The Fourth Industrial Revolution is Here – Are South African Executives Ready? noted that 73% of the South African executives surveyed saw a future where workers were completely replaced by autonomous technologies, rather than technologies augmenting workers. Globally, only 47% of executives saw that as the future.

Only 7% of South African executives felt prepared to address the uncertainty this would cause to their company’s workforce, whereas globally the percentage sat at 25%. A quarter of South African executives felt that the introduction of artificial intelligence would bring with it “social upheaval and increased income inequality”.