Rising from a green bottom to beat the water blues

Kat Swanepoel hated the pool as a child, but having discovered para swimming through a friend just two years ago, she is ready to represent Team South Africa at the Tokyo Paralympic Games.

Author:

18 August 2021

Kat Swanepoel was mesmerised. It was 2004 and Paralympic swimmer Tadhg Slattery had just claimed gold for South Africa in the 100m breaststroke (SB5) at the Games in Athens, Greece.

“It gives me goosebumps thinking of it. One of my first memories of the Paralympics was actually watching the Athens Games. I had always been fascinated with parasports, even as an able-bodied person, and then went on and trained as an occupational therapist. So it’s always been a passion of mine,” says Swanepoel, who qualified for her first Paralympics at the age of 33 this year.

“I remember watching this South African swimmer who’d just won gold and he signed the national anthem and I was, like, that’s phenomenal because I’d never experienced signing to music before. Never would I have thought that that guy signing the anthem would be my coach who would take me to the Paralympics, and that was Tadhg.

“There was no disability in sight for me at that stage, but I was so inspired by him, committing to wanting to work in the field. To think he’s the one to take me to the Games is just phenomenal.”

Since that inspiring scene, Swanepoel was diagnosed with progressive multiple sclerosis in 2008, which means she’s now paralysed from the chest down with weakness in her arms and hands as well.

Related article:

She only started swimming little over a year ago, just before the Covid-19 lockdown, but she knows all about high-performance sport having previously represented South Africa in both wheelchair rugby and wheelchair basketball.

Both sports eventually became too risky for her.

“I started playing wheelchair basketball first and then, when I started to lose function in my hands, I also started wheelchair rugby because you have to have an impairment in all four limbs. I really enjoyed the rugby, but unfortunately I just took too many knocks. It’s a full-contact sport so I started to have major neck issues and just decided it was playing with fire,” Swanepoel explains.

“I was fortunate to be able to continue with wheelchair basketball, but I was also taking a bit too much contact and ended up quite ill after the Paralympic qualifiers in Algeria. Three days in an Algerian ICU [intensive care unit] isn’t much fun. I think I just decided for health reasons it was time to call it quits on things. After that I did a bit of road racing just to keep fit, did a marathon and decided marathons are not for me. I’ve certainly been involved in quite a bit,” she adds with a smile.

A new direction

Speaking about her introduction to swimming, Swanepoel says: “My housemate is a physiotherapist and she travels quite a bit with the South African teams. She had been asked to go over with the para swimmers to the London 2019 world champs.

“So when she was watching the sport there and seeing all the different classifications of disability swimming, she phoned me up and told me I needed to start doing this. I had always swum as cross training in the pool but never seriously at all. I think I started mainly to keep her quiet; she’s rather insistent. But I’m thankful for her now.”

The prospect of being part of a team to represent her country on the greatest stage of all is a world away from the little girl who used to try to avoid school swimming.

“When I was a five-year-old in grade 1, I was so thankful that our school swimming pool was so green. I could walk along the bottom and pretend to swim. That’s how much I hated swimming,” she says with a laugh.

Fast-forward 28 years to the South African Championships in Gqeberha in April, and Swanepoel qualified for the Tokyo Paralympics in five events, setting multiple records along the way.

Related article:

“I have to admit I’m going a bit faster than I expected … I was actually really surprised, especially as it was my first time swimming in a competition with prelims and finals, which was a real learning opportunity. You can fix what you learnt in the prelim for the final,” she says.

Since then she’s been reclassified into a different class (S4, SB3, SM4) but will still compete in four events.

According to World Para Swimming: “Athletes are grouped by the degree of activity limitation resulting from an impairment. These groups are called ‘sport classes’.

“Athletes with different impairments compete against each other, because sport classes are allocated based on the impact the impairment has on swimming, rather than on the impairment itself.

Related article:

“To evaluate the impact of impairments on swimming, classifiers assess all functional body structures using a point system and ask the athlete to complete a water assessment.”

A general rule to make things clearer while watching Para swimming is that the lower the number in the class, the more severe the activity limitation.

With a condition that’s constantly changing, Swanepoel has to be acutely aware of what her body is and isn’t capable of and adjust accordingly. “That’s been one of the biggest challenges with a degenerative condition. With swimming training, sometimes some things don’t work quite as well as they used to work, so there’s a constant adaptation going on.

“But I think sports really helped me in terms of coping with that, because I think as athletes you’re so used to pushing your body to the limit and I think also focusing on specific movement. I think it’s helped me so much to cope with the degeneration of my condition,” she adds.

Measuring up to expectations

Even competing at the national championships came with its challenges in terms of gathering the confidence to perform in front of people who don’t always understand the world of parasport.

“I think there’s a lot of vulnerability that comes in it. I mean one of the biggest things I was worried about was the fact that I’m so much lower in terms of classification than the rest of the para-swimmers,” she says, referring to the Paralympic classification system that classes athletes according to the degree of activity limitation resulting from their impairment in order to provide a more level playing field. “Having all the Olympic swimmers there too … what’s good for me in the water looks like a drowning rat to them.”

Swanepoel is now classified as S4, whereas during 13-time Paralympic champion Natalie du Toit’s career, for example, she was S9 as she is missing a lower leg but the rest of her body is fully functional.

Related article:

“It’s just everyone’s watching and not necessarily understanding that, so I think it’s taken quite a bit of guts … for me to put a swimming costume on in front of everyone, and … also to just put yourself out there where you’re swimming very differently.

“I think, for me, I always appreciate it when people come and ask. You’d like to explain what the difference is between an S2 and an S10, and to explain to them that I don’t really have triceps, I don’t have hand function, I don’t have strong wrists, so everything for me comes from pecs and biceps.

“I think also what a lot of the other para swimmers have expressed is that sometimes the perception is that para swimming is easy because we do well in it. But the para swimmers are working just as hard, [if for] some of them not harder, than their able-bodied companions. I think that’s where the frustration comes in, that somehow people think you’re only there because it’s easy,” she says.

Tokyo ambitions

Swanepoel says some of those perceptions are changing, however, particularly after the London Paralympics.

“I think there’s been a massive shift from the 2012 Paralympics where, if anything, the Paralympics were bigger than the Olympics in London,” she says.

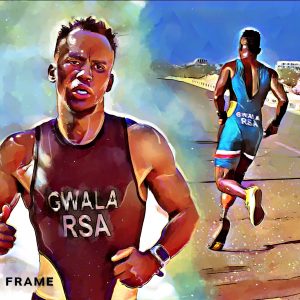

Last year’s Netflix film Rising Phoenix, featuring Australian swimmer Ellie Cole and South Africa’s own track star Ntando Mahlangu, among others, has also gone a long way to changing those perceptions.

“Rising Phoenix is just so awesome. It was brilliantly done, going into how the struggle to get that recognition has been there … I think it’s definitely making such a difference and I think telling people’s stories and saying these are my day-to-day struggles and then I’m still able to excel in sport on top of that.

Related article:

“I found a lot of the able-bodied swimmers at Nationals actually asking a bit more, and I was explaining about classifications and all that. Let’s just hope that that awareness grows … also, the understanding that we’re high-performance athletes, not just somebody with a sob story.”

While raising awareness and changing perceptions are certainly among Swanepoel’s goals, for now the main focus is hopefully emulating her coach in reaching that Paralympic podium.