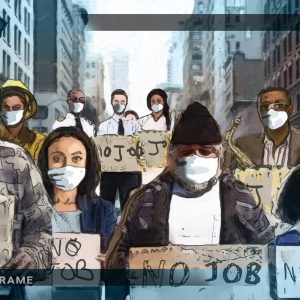

Richards Bay: The boom town busted by coronavirus

In this second instalment in a series on the coronavirus and capitalism, New Frame looks at how the once flourishing industrial town has been devastated by the pandemic.

Author:

18 August 2020

Boasting one of the largest harbours in South Africa, Richards Bay was once dubbed an economic powerhouse and gateway to the world. But the Covid-19 pandemic has exacerbated years of neglect, threatening the livelihoods of thousands of workers, most of whom come from the surrounding towns and townships.

According to the municipality website, companies such as Richards Bay Coal Terminal, Richards Bay Minerals, Foskor, Transnet, Alusaf (Bayside Aluminium Smelter) and Mondi created opportunities for the approximately 50 000 townspeople. But what was once an attractive place for investors has, over the past 10 years, seen mass retrenchments and the closure of many companies.

Better times

Richards Bay resident Timothy “Makoya” Gumede, 60, reminisces about a time when there were enough jobs to go around. “I was raised by a single mom who worked as a domestic worker, and so I was forced to leave school and get a job [to] help out at home,” says the man living in Esikhaleni township, about 30 minutes’ drive from the central business district.

In 1978, at the age of 18, he secured a job at Richards Bay Minerals, a company to which he has dedicated 41 years of his life. “Back then, there were many firms and the population was low. I was lucky to get a permanent job as a laboratory assistant. I earned R75 and that was enough to pay for my transport and buy groceries for my family. I had a good life.”

Gumede was able to feed his family, educate his three children, buy a house and a car and marry the love of his life, Busisiwe. “It was fantastic,” he recalls.

Related article:

But Covid-19 changed everything. He says the virus has had a devastating effect on older, skilled employees in the quiet town. “Workers who are over 60 and on chronic medication were told to go home in May and wait to be called back because they were high risk. Some people have returned to work. I returned to work after sitting at home for about a month.”

Gumede was one of few employees able to continue earning during the lockdown. Others were not so fortunate.

Retrenched workers

Welcome Buthelezi, 48, lost his job in March. The father of four from Cinci in KwesakwaMthethwa arrived at the Department of Labour’s offices in Richards Bay to apply for unemployment insurance fund (UIF) money at 7am to an already snaking queue.

“My boss called me and told me that I can no longer work for him because of Covid-19,” he says. Buthelezi was earning R1 500.

“The most painful thing is that I don’t qualify for a pension. I applied for the R350 grant assistance from the government, but they rejected my application because they said I was employed. I told them that I wasn’t earning much but they said no.

“I have been standing in the queue for so long, my knees are starting to ache. I haven’t eaten all day,” says Buthelezi.

Philani Nhlenyama, a National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) representative at Richards Bay Minerals, says the rate at which unemployment has been rising is alarming. “In the past, it was easy to get a job in Richards Bay, but now companies are retrenching left, right and centre. Some people have been forced to take voluntary retirement packages.”

Bongani Nxumalo, 31, is originally from Jozini, northern KwaZulu-Natal, two-and-a-half hours from Richards Bay. He also lost his job during the hard lockdown when the Johannesburg company he had worked for since 2015 was shut down.

“When the president announced lockdown the company I worked for closed, and we waited at home for them to call us back. But they didn’t. So when the lockdown regulations were eased and we could travel, I decided to go back to Esikhaleni, where I am renting a room.”

Nxumalo says his employer called him in June and told him the company was closing. “We walked away empty-handed and now we have no choice but to apply for assistance from the state. I know that there are no jobs at the moment, but I have not given up. Every morning, I go out to drop my CV because I have hope that things will get better.”

Not too far from Nxumalo sits Ayanda Madlobhe, who is nine months pregnant. She is on the floor, filling in UIF application forms. The 31-year-old came from Mandeni, an hour’s drive from Richards Bay.

“I have no idea how I am going to support the baby now that I have lost my job. I have to look for another job, but at least my partner is still employed so he will be able to help,” says Madlobhe.

Mnqobi Myaka, chairperson of a recruitment initiative that works with the KwaMbonambi Tribal Authority, says the job losses have had a devastating effect on the young people in the area.

“Most of them gather in groups on street corners, while some have resorted to crime. Some of those who were in university came back and have been influenced into bad behaviour because there is nothing much to do except commit crimes and drink alcohol,” says Myaka.

For Zama Nzuza*, 39, from Emabhaceni in Empangeni, her fear of being unable to provide for her children became a reality when the company she had been working for since 2008 shut down.

“Problems began in February last year. We saw a decrease in the orders and our boss told us that there were challenges because of the drought, so it is not that we are blaming Covid-19 for everything.”

Podcast:

Nzuza says the pandemic has only made an already volatile situation worse. “The farming industry was already struggling before the pandemic. Our boss tried everything in his power to save our jobs, but he struggled. We received retrenchment letters, and we were told that the company was closing at the end of July.”

The mother of two earned between R5 500 and R5 800, depending on how often she worked. “I am really heartbroken about losing my job, but there is nothing I can do about it. Even our white bosses were crying, so it is not a thing about race. Everyone is affected.”

These days, instead of waking up early to get ready to go to work, Mbali Ngcobo*, 32, from Ngwelezana, sleeps in until 10am and spends most of her day at home. She worked as a cleaner at the Umfolozi Hotel Casino Convention Resort in Empangeni and says they were told to go home on 24 March 2020.

“It was not long after that we were told that the contract of the company we were working for was not going to be renewed … The hotel couldn’t afford to pay because there were no customers. I suppose we should thank [President Cyril] Ramaphosa for increasing the child grant because that is what is going to help me right now.

“To be honest, I was not ready for this and neither did I expect something like this to happen. I was renting a room at the back of a house and the landlord offered me and my children a room inside the house, because I couldn’t afford to pay the rent.”

Unemployment at 50%

Ntokozo Ngwenya, the local secretary for the Congress of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu), says mostly smaller companies subcontracted to provide services to bigger ones have been affected. “It’s sad because Richards Bay was once known for being the most developing small town in the country. Now that is not the case.”

Most employers are citing the lockdown as the reason for closing. “There is a lack of demand internationally and that means local companies will struggle to keep their doors open,” says Ngwenya, adding that this will have a devastating effect on the surrounding areas that depend on Richards Bay.

Irrshad Kaseeram, deputy dean in the economics department’s commerce faculty at the University of Zululand, says the rate of unemployment in the King Cetshwayo District Municipality is a staggering 50%.

Related article:

Kaseeram attributes this to the inaccessibility of employment for people living in the rural areas surrounding Richards Bay. “Research has also shown that the discouraged-worker effect is extremely high. People got tired of looking for employment and ended up settling for casual work like domestic work, gardening and looking after their relatives’ children.”

This means that most people rely on remittances from their loved ones who have stable jobs in bigger cities, where salaries are higher. “There are a lot of people who are also depending on the social grants earned by family members, because most of the heads of the homes are elderly.”

Many people now live below the poverty line of R35 a day. “Life is really tough and Covid-19 has exacerbated what was already a difficult situation. Casual work took a knock, especially in the first two months of lockdown, and it was only when the regulations were eased that things started to get better,” says Kaseeram.

With businesses closing down, families are getting much lower incomes. “The economic uncertainty over the last 10 years has seen companies investing less because of the global recession and a lack of good governance.”

Kaseeram also blames the job losses on former President Jacob Zuma. “The Zuma regime favoured the Chinese, and so a lot of the American and European companies in the area were sidelined.”

But all is not lost, says Kaseeram. “There is great potential for financial recovery, but we are going to have to follow a business-friendly policy to attract businesses to invest in the local economy.”

*Not their real names.