Resisting the far-right and its trolls

White supremacists use the internet to spew myths of victimisation that legitimise racist ideologies. Their attempts to silence critical voices in the South African media must be opposed.

Author:

31 January 2020

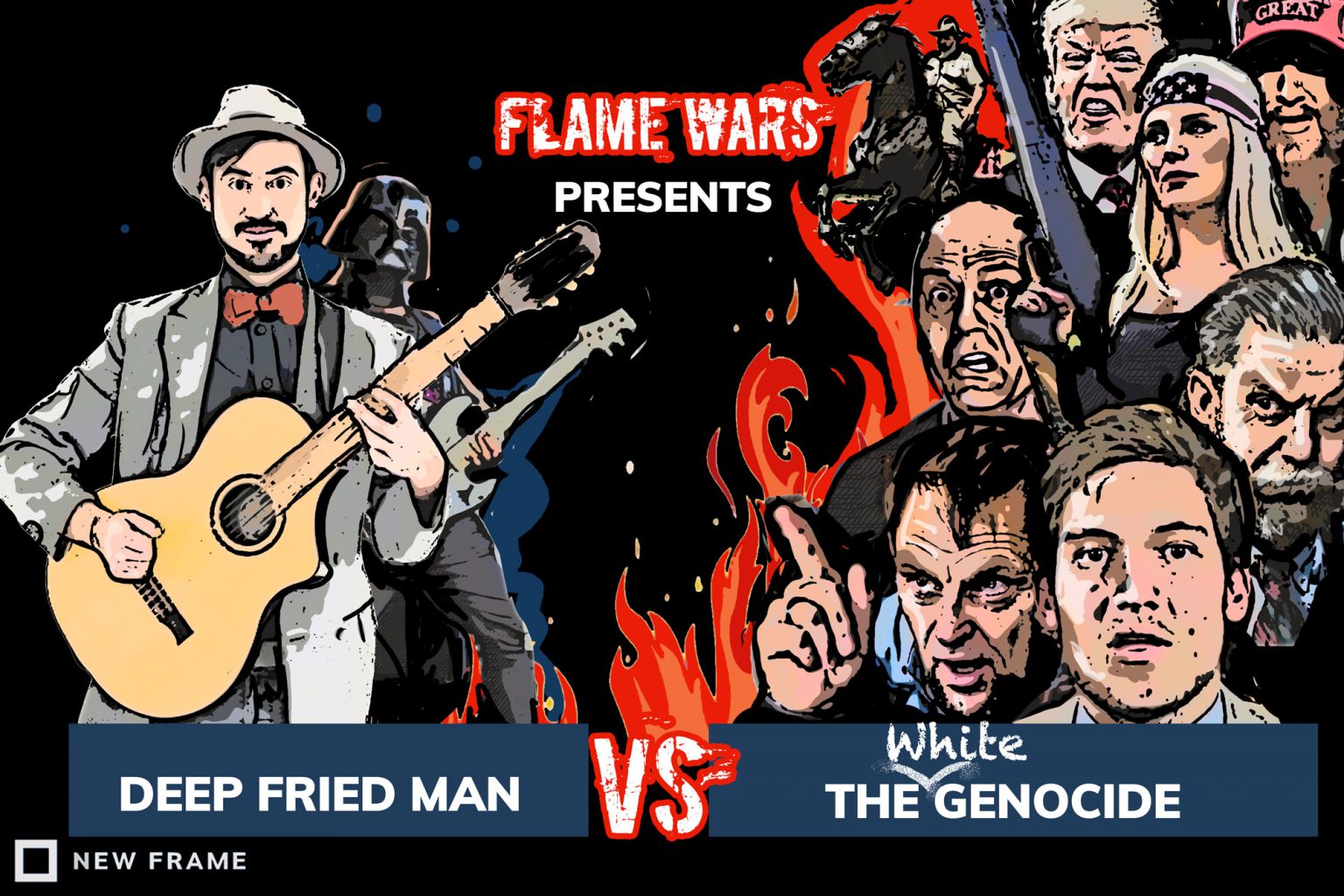

As the South African National Editors Forum (SANEF) has noted, far-right activists have launched a campaign to silence Daniel Friedman, the digital editor of The Citizen. Friedman, who also performs satirical material under the name Deep Fried Man, was forced to quit his social media platforms after antisemitic comments and personal threats to his safety.

The Citizen has since placed Friedman under suspension after receiving complaints about social media posts that mocked white nationalists. This campaign was spearheaded by Willem Petzer, a popular figure within the far-right social media ecosystem. In a YouTube video, Petzer claims that Friedman is personally defamatory and hates white people. He encouraged the “good, ordinary people” of South Africa to complain to The Citizen.

But Petzer is hardly a disinterested member of the public. He is a political activist whose goal is to bring attention to the supposed persecution of white South Africans. The day before he released his call to end Friedman’s “hate speech”, he tweeted that Jason Bartlett, who is currently publicising the racist myth of “white genocide” to an American audience, is his “brother in Christ”.

He also clearly has a personal vendetta against Friedman. In the past, Friedman has exposed Petzer for his private support of Nazism and apartheid. It’s also notable that Petzer’s campaign was supported by online right-wing influencers, such as the notoriously racist lounge singer Steve Hofmeyr. Many of the social media comments about Friedman were overtly antisemitic, with right-wingers alluding to the supposed Jewish control of the media.

Given the evidence, it seems this orchestrated campaign was intended by Petzer to both silence and get revenge on a critic. On a practical level, it should be noted that his definition of “hate speech” and “anti-white racism” really just means people condemning his extremist views.

Related article:

As Imraan Buccus wrote in The Daily Maverick, this case is an example of how social media can be used to orchestrate vindictive and highly deceptive politics. In the world of right-wing “alternative” media, people like Petzer use highly biased and false reporting to encourage their followers to target their perceived enemies, such as critical journalists and left-wing activists. To maintain an audience with today’s short attention spans, they continually need to agitate digital mobs with inflammatory stories. The South African iteration of this is a new online white-victimisation industry, rooted in a host of paranoid myths.

The myth of the white victim

Petzer and others claim that terms like “right wing” and “white supremacist” are slurs used to stifle debate and silence the legitimate grievances of conservative whites. In reality, a vast amount of journalistic and academic research shows that there has been a dramatic, global escalation in radical far-right activism in the past decade. The far-right has dropped much of its historical symbolism and language, adopting more subtle racist and xenophobic dog whistles to attract a wider audience. This has been bolstered by the internet, which makes extremist propaganda easily available.

This online culture has been further inflamed by the political success of politicians like Donald Trump and Jair Bolsonaro. While they may publicly disavow neo-fascists, they regularly endorse their conspiracy theories and beliefs. White nationalists and the so-called alt-right, a millennial rebranding of traditional racism and misogyny, feel newly empowered in the present political movement. This has also resulted in a string of killings and terror attacks, such as the Christchurch mosque shootings.

Terms like fascism and the far-right are never fixed, as political tactics and imagery change over time. But political and sociological research since World War II show there are certain family traits shared by all far-right movements. These include ultra-nationalism and a belief that a chosen group is under siege from its enemies, an obsession with returning to the social hierarchies of the past and a profound hatred of both the political Left and humanist cultural values.

The contemporary far right tries to obscure its intentions by shifting the burden of proof onto its critics, claiming that unless they are caught walking around in SS uniforms, they cannot be credibly accused of racism. But fascism is as much a state of mind and cultural outlook as it involves overt political mobilisation. One can track a direct ideological through-line from Petzer and Hofmeyr today, back to Eugène Terre’Blanche and groups like the Ossewabrandwag, which fused Nazism with Afrikaner nationalism.

Legitimising racist ideologies

What has changed is how these views are expressed. Rather than openly calling for white domination, they use liberal human rights language to perpetuate the claim that white South Africans are the target of various rooi and swart gevaars (the red – or communist – and black perils). South African white nationalists are also trying to gain attention within the US and Europe, using exaggerated claims about farm murders to gain attention. Along with South African militia members openly marching with American neo-Nazis, claims of white genocide have been repeated by Trump himself and dubious characters including Lauren Southern, Gavin McInnes and Stefan Molyneux.

By using coded, subtle language, the far-right also hopes to gain credibility with conservatives and liberals. This is further enabled by the conservative scapegoating of Muslims, immigrants and trans people, among others, and a wave of anti-intellectual hysteria about “woke culture”. Far-right activists appeal to a less radicalised audience by claiming to be independent thinkers who are being silenced by totalitarian leftists.

Related article:

The irony is that it is the hard right who truly hates free speech and independent journalism. There is ample evidence of them conspiring with violent far-right groups, launching vicious doxing campaigns, which involves putting people’s personal information online, and inciting street violence against journalists and antifascist protesters.

The South African media has rightly condemned organisations like the EFF for their harassment and slander of journalists. But equally, the actions of white supremacist provocateurs and trolls need to be challenged. Suspending Friedman on the basis of a special-interest campaign organised by political extremists sets a bad precedent for dealing with media accountability.

The emboldened far-right alternative media claims to be committed to free speech and uncensored thought, but in practise their focus is on winning renewed legitimacy for racist, sexist, homophobic and xenophobic ideologies. Their long-term goal is to redefine our political and cultural language, which is why they regularly accuse critics of reverse racism and discrimination. They are bad actors, using human rights language to shield themselves from legitimate and substantive critique.

Willem Petzer’s videos and tweets reveal a profound hatred of South African democracy and the values espoused in the Constitution. Ironically, it’s the civil liberties gained from democracy that allow him the freedom to spout his reactionary and ill-informed views.

But the mass media is under no obligation to give him a platform or give credibility to his personal campaigns. Given this country’s white supremacist past, and the current global climate of right-wing populism, silencing Friedman only empowers voices that contribute nothing valuable or constructive to the national conversation.