Remembering history with Kudzanai Chiurai’s library

The Zimbabwean artist has created an extraordinary listening space filled with vinyl records of historical import ranging from political speeches to African struggle songs.

Author:

3 November 2021

“I have always imagined that Paradise will be a kind of library,” wrote Argentine poet Jorge Luis Borges. With The Library of Things We Forgot to Remember – a listening library in a bustling Johannesburg hub – artist Kudzanai Chiurai has created a space unlike any other in South Africa. It houses rare African records of music and political speeches, and the public can listen to all of it for free.

The Zimbabwean artist, who is based in Harare these days, has spent many years moving between South Africa and his place of birth. Known for artworks across multiple mediums, including films, paintings and sculptures, Chiurai has been incorporating the idea of a library into his work over many years.

Though his collection looks like it’s been gathered over a lifetime, Chiurai only got into collecting records in 2007. He explains that it began through the influence of his friend Kenneth Nzama, aka DJ Kenzhero, whom he met while studying at university in Pretoria. “He has an insane vinyl collection. That kind of schooling through that friendship was very important.”

Initially the process was slow, but after moving back to Zimbabwe in 2014 Chiurai started collecting more seriously. The discerning way in which he did so turned the result into a highly prized and rare collection of African records.

The idea for the library took root when Chiurai had his first solo exhibition in Zimbabwe in 2018, in collaboration with the Pan African Space Station, hosted by Chimurenga. People could select and listen to records displayed on the walls of the gallery, and these were also used in the station’s broadcasts. “In seeing how people responded to the library, I thought it was important to make it more solid and have it as a more permanent feature of my art practice,” Chiurai says.

Thereafter, he took the idea to exhibitions he had in Cape Town, Sweden and Johannesburg, hauling the records with him. Each time the library moved to a new place, a new librarian was chosen to participate in the selection process. As his collection grew, the need to find a physical space to house the archive became important. From a logistical perspective and because of his representation by the Goodman Gallery in South Africa, it made sense for that space to be in Joburg as opposed to Harare. But the premise of the library is that it can and will travel.

A continent in a room

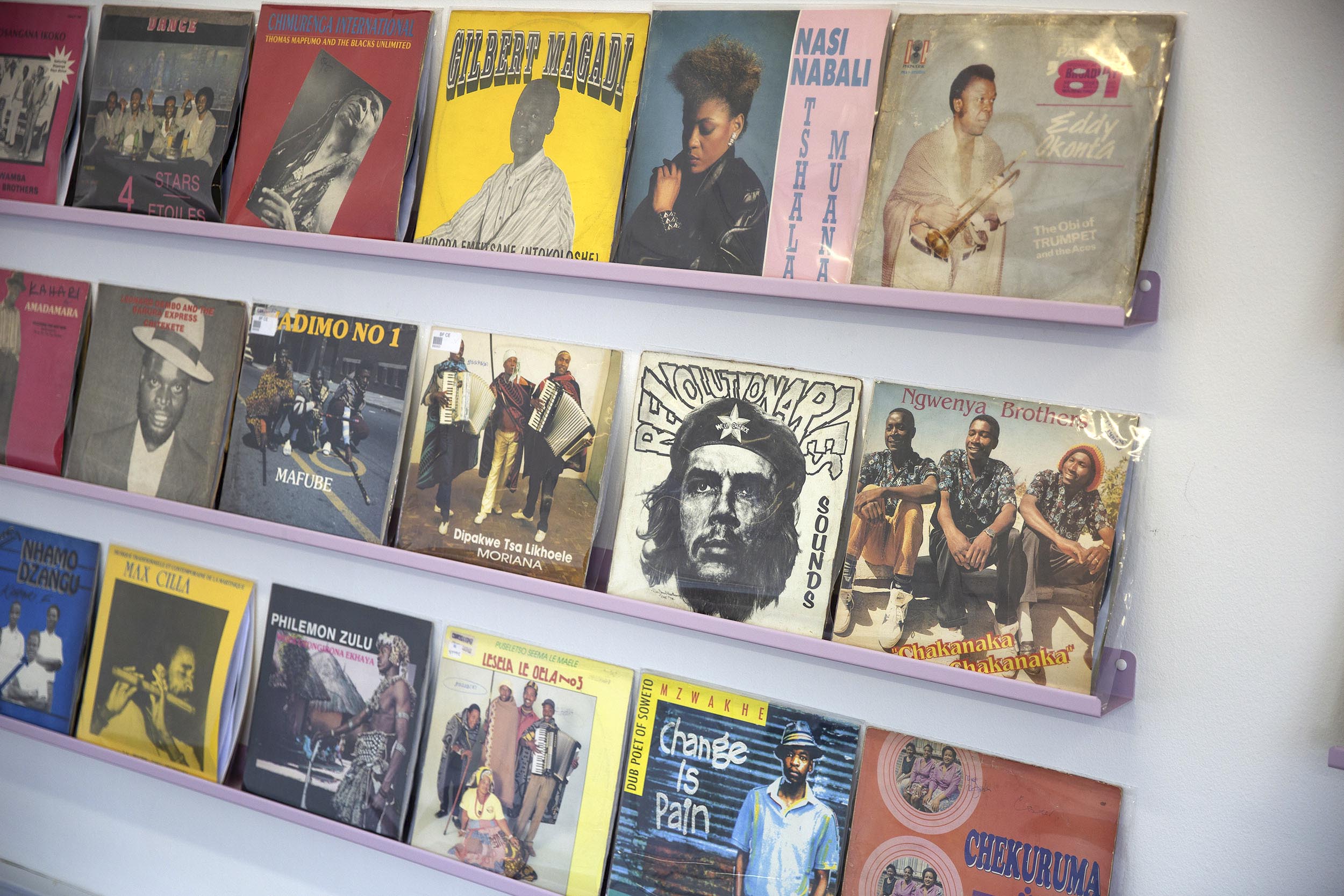

The library is housed on the first floor of the 44 Stanley creative hub in Braamfontein Werf. Entering the space, a wall to the right displays several records on a shelf. Across from them are record players at listening booths with headphones. Artworks and photographs hang on the walls.

Opened in May 2021, the space continues to evolve. It is open to anyone to visit, pick out and listen to records from Chiurai’s collection for as long as they want. For most record collectors around the world, preserving an album in mint condition is the goal as it retains value this way. However, this process is inverted in The Library of Things We Forgot to Remember, where there is no control over who handles the physical object.

The bulk of the collection focuses on music released during the period of independence in Africa from the mid-1960s onwards. “We cover at least 80% of the African continent in language, in diversity and in political and historical thought,” Chiurai says.

While the space opened with an exhibition of Chiurai’s work and the corresponding albums he selected, it will change regularly as new artists and different music librarians are chosen. “It seeks to find connections between the visual arts and different art practices and connect those archives to the contemporary,” he says. Apart from records, there are artworks, books, posters, prints, maps, journals and zines.

Chiurai is continuously adding new records to the library, whether through donations, finding them on his travels or sourcing vinyl online. New additions include the poetry of Margaret Walker, the Autobiography of Frederick Douglass, Eldridge Cleaver recorded live in Syracuse and Amandla: African National Congress Cultural Group.

He also got the rights to host digitised material from The Freedom Archives housed in the United States, which has extensive archives on liberation movements in Africa. “I’ve been trying to find other institutions who are open to the idea of open access and giving us rights to the material. It’s an important part of what I hope the library does in the long term,” he says. Additionally, Chiurai hopes to transfer this material to vinyl to make the archives more accessible.

Capturing the source

The records Chiurai has collected are important for the fact that they are rare and often don’t exist in any other audio format. The albums reflect history and together provide a critical source of raw study material that shows how culture is rooted in politics.

This is important considering how African records are mined globally to the point that they have become inaccessible to people on the continent, often sold for exorbitant prices online. For example, one is more likely to find Abdullah Ibrahim records in Europe than in South Africa.

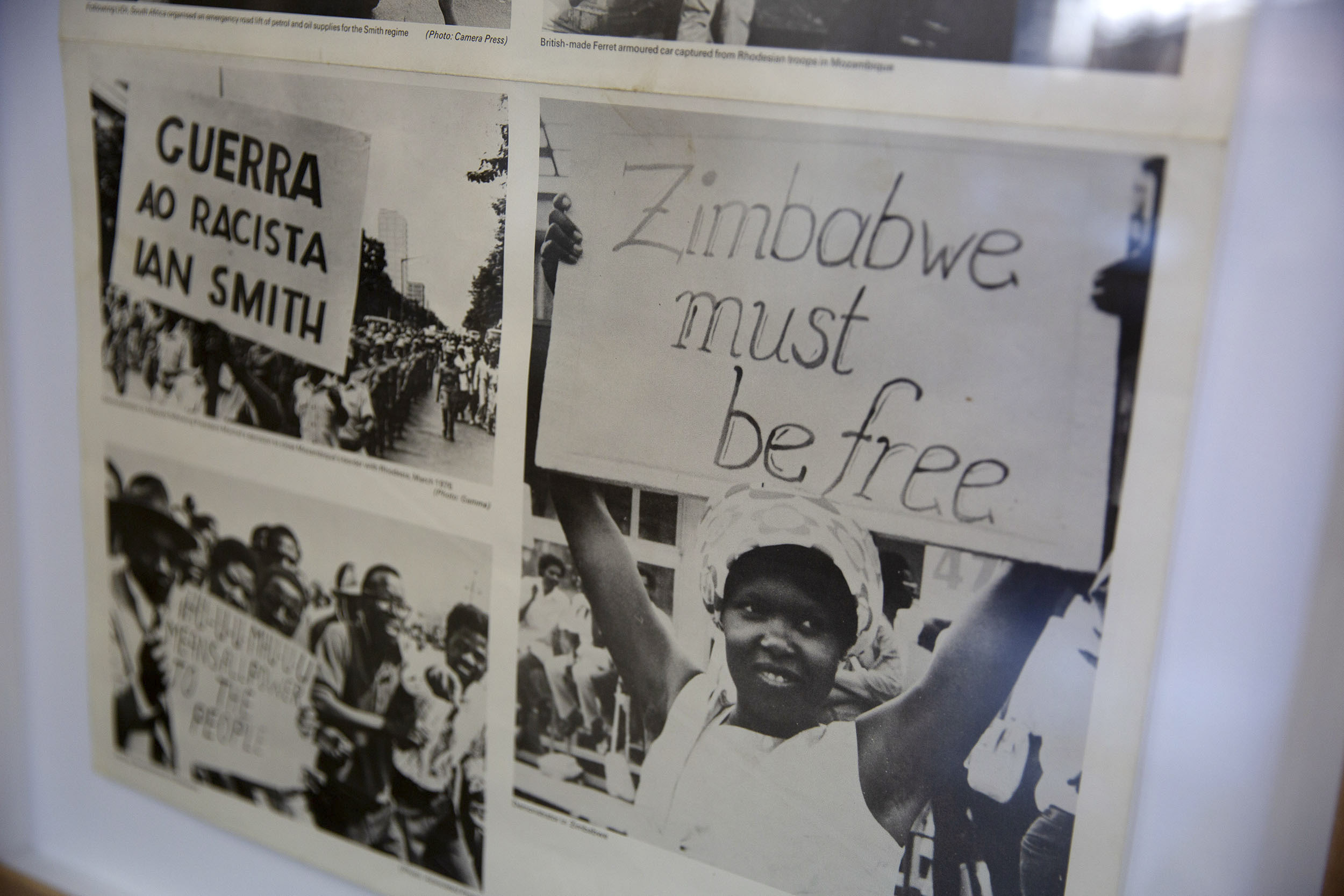

Added to the rare music is a growing list of historical political speeches by figures such as Ian Smith, Kwame Nkrumah and Mobuto Sese Seko that have been captured on vinyl. Chiurai has made a special effort to collect these.

“That was very intentional. A lot of those recordings are located in institutions and the idea of access comes into question. Looking at the collection itself, it shines a light on an important part of Africa’s political thinking. You can’t really separate the music from the political activity and therefore the speeches also had to be an important part of the collection.

“So much of what we learn from that period has been through text, but now we also understand through sound,” he says. “Some of the recordings were recordings made in liberation zones in Angola, in Guinea Bissau, Algeria, Eritrea and Mozambique. That’s also significant in understanding our political history. The sound comes from the very locations within which these political ideas were shaped. And it’s important to hear that in the first-person voice.”

This first-person narration provides a personal perspective on history and it is quite different learning about it this way rather than through academic journals or texts.

“In that regard, you’re listening to that very moment and how that speech or that conference shaped our political thinking in the years that followed,” Chiurai explains. “We realise that some of the people that made the speeches are still living, so then we can reflect in the sense that we can bring them to account for the things that they’ve said.”

The title of the space suggests the importance of memory and reflection. “It’s always this connection to the past,” says Chiurai. “What are we told to remember? How do we remember those events? How are those ideas told to us?”

Let it be

In terms of his own art practice, Chuirai uses the space as a source for reference material and a learning tool, just like one would any other library. He says creating the library has helped expand his understanding of music.

“What I thought was important was that the [vinyls are] made with a specific lifetime, so let that be the life, let people listen to them. If they are damaged in the process of being listened to, let that be the life process. Let’s not be so precious to the point where we can’t listen to the material. They were made to be listened to. Even the idea that the sound will start to deteriorate over time – let that be the quality.

“I’ve had friends who came with their kids. And it’s interesting for them, being able to go and select the vinyl, learning how to use the vinyl player, listening and then putting it back again. The physical process is also a change from going into an art space and not touching anything.

“But I also think it’s important that within the life of the library, it’s not a library about archives. It’s essentially a living library, so we start to collect and transfer material on to vinyl.” The long-term goal is that it’s not static and will continue to add more recent material made during turning points in African history.

Flipping the idea of conventional libraries, he says: “You often don’t see yourself in those libraries, right? You see a government mandate of what a library should have and what you should be reading, whether it’s Western books that reflect a European sense of knowledge or English-language books.”

Chuirai credits the space for helping him develop his own understanding of the evolution of African political thoughts on freedom and independence. “This library is one of the few instances that I see myself, as opposed to trying to find myself in a library. I see myself as an African and I see myself as a Zimbabwean. It reflects a cultural and political history I was never particularly familiar with. So the more I get familiar with it, the more I see myself in that. I see my Blackness in that. I think that, for me, was an important shift.”