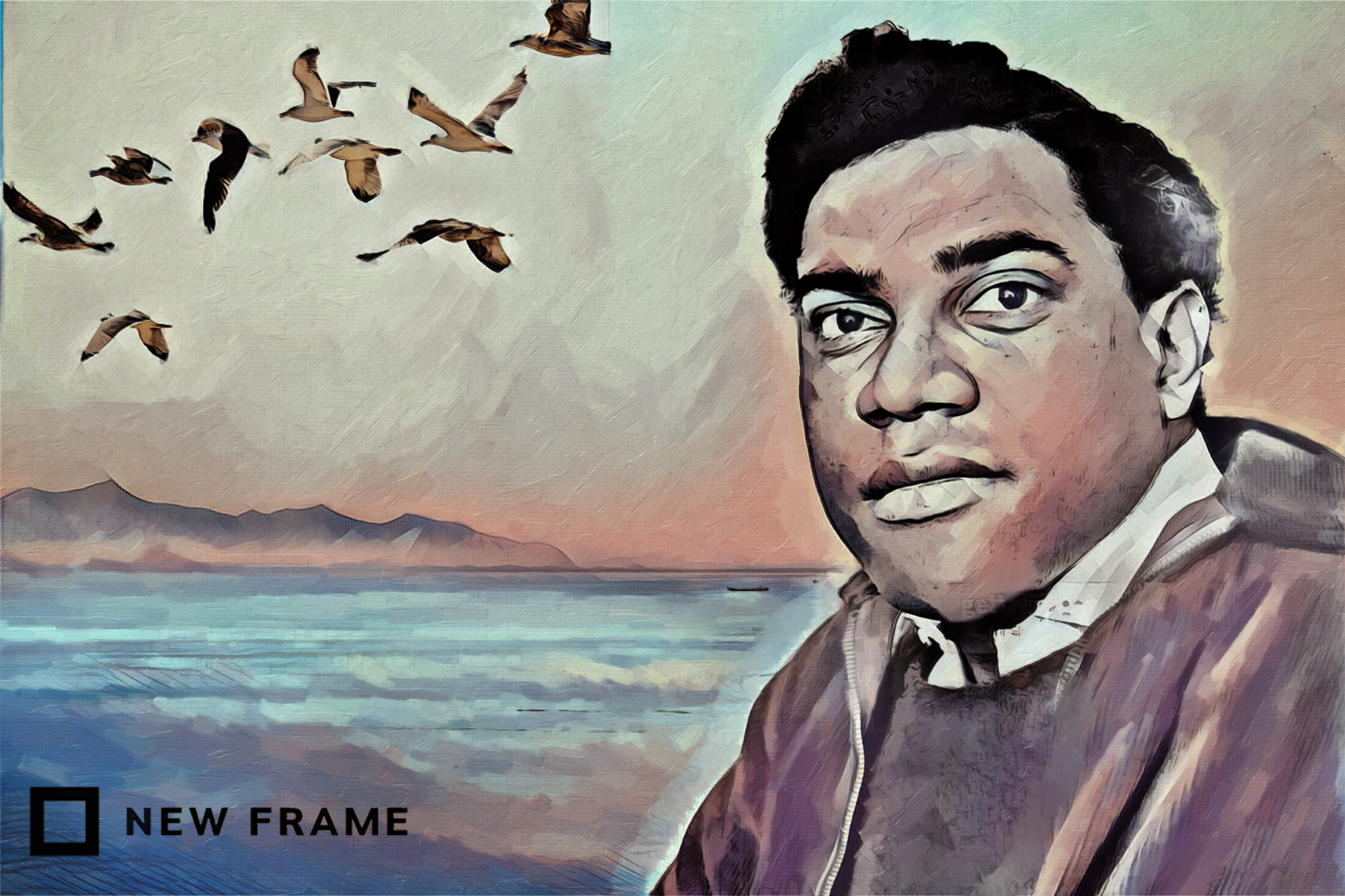

Remembering George Lamming’s spirit of generosity

The Barbadian novelist, poet and essayist was a consummate ‘mental worker’ who played a profound role in shaping the postcolonial Caribbean national identity.

Author:

15 June 2022

With the death of George Lamming on 4 June, four days before his 95th birthday, we lost our last living connection to the generation who laid the spiritual foundations for Caribbean independence. Lamming was born in Barbados on 8 June 1927, but he understood that rock as only one parish of a scattered nation. He belonged to the entire archipelago and its diaspora, and the loss of his mighty voice, a cerebral, troublemaking voice, a steel band of a voice that unravelled complexity through a logic of tones, is felt as bitterly in Port of Spain and Havana, London and Toronto as on his island.

He was the only child of Loretta, who, in a familiar pattern, sacrificed alone to raise her son in an urban village near Bridgetown. It was an education in the violence of race and class. To cross a narrow street from Carrington village to middle-class Belleville was to arrive on pavements where guards and dogs were free to bully small boys. At 10, he witnessed the eruption of the 1937 riots, and when a scholarship to Combermere School divided him from his working-class childhood, he carried the village with him. He would wrestle with those memories and the unsettled business he had left behind for the rest of his life.

At Combermere he was discovered by the teacher Frank Collymore, who encouraged him to find in the power of words a vehicle for his hopes and anger. Collymore had edited the pioneering literary journal Bim from 1942 and Lamming, like Derek Walcott and so many others, would first experience writing to be read there. Lamming could have been a cricketer – he was a promising batsman who once played for empire – but Collymore made him want to make writing his life.

Related article:

After Combermere he went to teach at a school for Venezuelan children in Trinidad. There he became comfortable in Spanish, which later made him one of, sadly, a tiny number of Anglophone Caribbean intellectuals who could speak to Nicolas Guillen and Fidel Castro in their own tongue. But in a much larger sense, Trinidad, as Lamming later said, “completely changed my head”.

In Port of Spain he was swept up in the extraordinary intellectual, political and artistic life of what was really the cultural centre of the Anglophone Caribbean. He met calypso, steel band, Shango, Marx and Lenin, keeping company with the dancers, actors and painters, sculptors, Eric “Bill” Williams and Paul Robeson who circulated around the Belmont and Woodbrook homes of people like Beryl McBurnie. There he met the artist Nina Ghent, the only woman he married, with whom he would have son Gordon and daughter Natasha. He had arrived in Trinidad an anxious Barbadian poet, but he left in 1950 as a man who thought himself a West Indian, a Marxist, and wanted to write a novel.

London introductions

He shared a cabin and a typewriter on the sea voyage with another man with similar ambitions, Samuel Selvon. Arriving in London in April 1950, he began feverish work that would yield, over two decades, the body of novels and essays for which he would be most famous: In the Castle of My Skin (1953), The Emigrants (1954), Of Age and Innocence (1958), The Pleasures of Exile (1960), Season of Adventure (1960), Water with Berries (1971) and Natives of My Person (1971).

In London he had a second apprenticeship, learning to use the full power of his voice as a reader for the BBC. He muscled up before British microphones, the rhetorical arts of what he later described as trying to make thinking feel. The legacies of that training would remain to the end of his days, and not only in the slashes and BBC reader’s marks of the manuscripts of his speeches and lectures.

Related article:

In London, too, he began his important friendship with CLR James, and a discerning eye will find Lamming’s mark in the famous appendix to the 1963 edition of Black Jacobins. The anchor of these decades was his long relationship with the South African Jewish political exile Ethel de Keyser, whom he met at the first meeting of the Anti-Apartheid Movement, and they came to share a home in Hampstead.

Castle’s fame catapulted Lamming to a new international trajectory. At the Congress of Black Writers and Artists in Paris in 1956 he met Césaire, Senghor, Fanon, Glissant, Jean Price-Mars, Cheikh Anta Diop, Richard Wright, Jacques Roumain, and De Beauvoir and Sartre (who had parts of Castle translated into French). He came to a new understanding of himself as part of a global Africa, even as part of a whole colonial world, in insurrection against material and moral dispossession.

Task of struggle

In Haiti in 1956, he had a life-changing religious experience. He was ushered into a vodou temple. There he was part of a celebration of the ceremony of souls, the ritual where the living enter into a conversation with the dead, seeking to liberate them from all pettiness and rescue for eternity the highest moral purposes, the gwo bon anj, to guide the future of the community.

He came to understand the Christianity of his Bajan childhood, the transhistorical ambitions of his politics, the aching fracture in himself between the village that had made him and his sound colonial education, his work as a writer with a new clarity as a task of struggle and reconciliation, a battle of the living against all the waste of mortality, of poverty, of that alienation of hand and mind which he thought was the cardinal evil of capitalism. He returned again and again to the meaning of this experience, especially in the novel Season of Adventure (1960).

Related article:

Season offered a dark prophecy about the West Indies Federation, and indeed about Caribbean political independence. It warned of the danger of the chasm in language, culture and power that separated the educated elite of “Federal Drive” and the working masses of the “Forest Reserve”, whose creative energies were as overflowing in the steel band as they were in the politics of insurrection. The material poverty of the masses was entangled with the colonised spiritual poverty of the elites. Later, when receiving his honorary doctorate from the University of the West Indies (UWI) in 1980, he would reflect on “the old white planters who derived their power from what they owned” versus “the new black planters who derive their power from what they know”.

Of course, as Andaiye explored in a brilliant essay, the quality of this betrayal of a new political elite of those who produced and followed them had already been explored in the character of “Mr Slime” in Castle. Lamming’s later decades might be seen as a long war against this chasm, this colonial legacy of alienation. He took on himself the work of being a kind of secular houngan (male vodou priest), who would engage the liberating power of the ceremony of souls, that work of struggle against silence and alienation, in every theatre to which he was given access.

Pulled to the Caribbean

As the season of political independence opened in the Caribbean, Lamming spent increasing periods back in the Caribbean. At the Mona campus of UWI in Kingston, Jamaica, in the early 1960s, he kept company with Sylvia Wynter and the then undergraduate Sandra Williams (later Andaiye). In 1966 he edited the extraordinary Guyana and Barbados independence issues of New World Quarterly. He built a web of correspondence with West Indian writers and intellectuals everywhere, becoming their most important common point.

I was not yet two when he came to stay at our house. He was sought out by Eric Williams of Trinidad, Forbes Burnham of Guyana, and especially Errol Barrow of Barbados. It was then too, in the early 1960s, that he first visited revolutionary Cuba, beginning a relationship with its poets and novelists like Guillen, Carpentier and Morejon that would endure in his role in Casa de Las Américas.

He was aching to get home, but saw no way to make a living. His dream was to be at the centre of a labour college in Barbados, but his dangerous politics made that impossible. His solution, one which would last into his 80s, was to teach for semesters in the United States, earning what he needed for the rest of the year in Barbados. The US had its own catalytic impact on him, in particular the political clarity of African-American artists like Baraka and the poet Sonia Sanchez, his partner for a season.

Related article:

But the convergent impact of the Grenada Revolution and the coming to power of Thatcher, and an important relationship with the paediatrician Esther Archer, led him to return permanently to Barbados around 1980. His base became the Atlantis Hotel on the east coast of Barbados, where each Sunday his lunch table became the place where the thinking life of the island found its highest pitch. For a tempestuous decade, punctuated by the murder of Walter Rodney and the suicide of the Grenada Revolution, Lamming tried to bring together the “mental workers” of the whole region into alliance with revolutionary change in organisations like the Committee for the Cultural Sovereignty of the Caribbean.

He travelled and spoke in literally every part of the archipelago, Suriname and Guyana, where he was briefly arrested and imprisoned by police at a demonstration. His close collaborators in this period were Kathleen Drayton, Rickey Singh and Andaiye, with support coming through Michael Manley and his connections as well as the Oilfield Workers’ Trade Union of Trinidad and Tobago. At the same time, in Havana, he collaborated with Garcia Marquez, Juan Bosch, and others in the Committee for the Cultural Sovereignty of the Americas. In this period he also ghostwrote speeches for three Caribbean prime ministers.

The winter days

In the 1990s and 2000s, through teaching posts at the City University of New York, Brown University and finally, at last, at the UWI in Barbados, Lamming had a significant impact on younger generations of writers. Among them was the poet Esther Phillips, who would rescue him in her home when the Atlantis Hotel was sold and be his partner in the winter days of his life. The importance of the body of work of speeches and lectures that he had begun in 1960 was collected and recognised in collections such as Conversations (1990) and its successors. One of Hilary Beckles’s finest acts as principal of UWI’s Cave Hill campus was to create around Lamming a centre where he could sit in his office and edit a relaunched Bim.

But Lamming never ceased fighting. He felt urgently that the regional ambitions for the Caribbean that his generation had lived for were at risk and, worse, that a new kind of alienation and recolonisation had come in a region where all attention was turned to the celebrity mediocrities of the US and where, to get from Barbados to Jamaica, one often had to fly to Miami first. He continued to make speeches that made politicians cringe, and challenged his listeners to want more than the power to consume.

Lamming received many honours at home, including the Companion of Honour of Barbados in 1987 (he, with Kamau Brathwaite, having indicated privately that they could not accept a knighthood), and an honorary degree in 1980 from the UWI. Internationally he won many distinctions, including a Guggenheim Fellowship (1955), Somerset Maugham Award (1958), the Langston Hughes Medal (1998), Fellowship of Institute of Jamaica (2003), and the distinction of which he was perhaps proudest, the Order of the Caribbean Community (2008).

Lamming leaves behind a daughter, seven grandchildren and nine great-grandchildren. He leaves behind a rich legacy for us, too. It is now our hard and bitter work to make sense of his life and our loss, and to rescue from the waste of mortality all his generous and heroic ambitions. As he said himself once in a ritual of mourning, the ceremony of souls is never at an end. Wherever we work for the liberation and unity of the Caribbean, the spirit of George Lamming will be our companion.

This article was first published by Stabroek News.