Rebuilding wounded dreams – workers as writers and artists

Despite all the great art created by organised labour during the struggle, since democracy, there has been a paucity of artistic production from the rank and file. It’s time we emboldened workers t…

Author:

14 September 2018

Up till now, Black workers have been parading, boxing, acting and writing within a system they did not control – all their creativity has been fed into a culture machine to make profits for others. It is time for us to begin controlling our creativity. We must create space in our struggle through our own songs… (Federation of South African Trade Unions, Worker News, 1985)

The powerful ask / Who allowed these stalks of cane, these blades of grass, to sing? / Songs are the property of trees, you have to be tall / you have to have substance, stature and trunk to sing / But we sing / Many with eyes get confused by the stature of trees / But at least our song reaches the blind / They listen to it closely / and understand… (Alfred Themba Qabula, In the Tracks of Our Train )

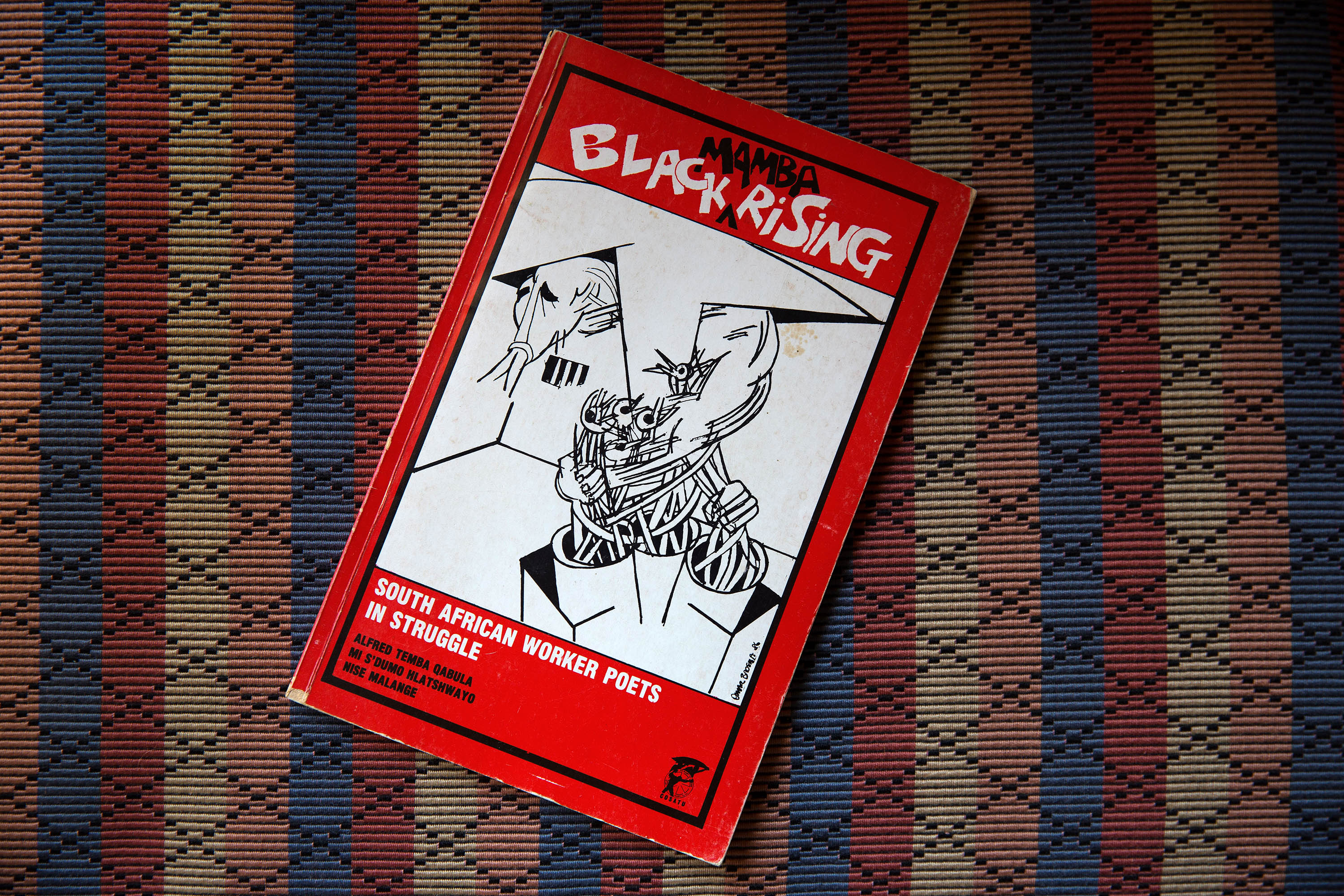

Poet, union militant and forklift driver Alfred Themba Qabula (1942-2002) never doubted the right of workers to sing: to create drama, music, art and literature expressing their lives and building their shared struggles. Qabula was part of a rich, diverse South African artistic movement that developed during the 1970s and 1980s.

Innovating from pre-existing creative practices in their communities, and from the Pan-African and international examples of resistance culture they encountered, organised workers shaped a visual language through posters and banners, wrote and performed poetry, created plays such as Bambatha’s Children and The Long March (which toured internationally), and added a new genre, mzabalazo, to choral music, fresh in subject matter, costume and gesture. “Hlangelani basebenzi nibe munye,” sang the Braitex Choir, “Ukuze sinqobe abaqashi ngengeni (Come together workers and be one so we can defeat the bosses with our numbers).”

Qabula’s autobiography, A Working Life Cruel Beyond Belief , was relaunched at the Jozi Book Fair, held at Johannesburg’s Mary Fitzgerald Square during the first weekend in September and themed around worker culture. During the two-day fair, the same questions kept arising: why did this heritage of worker culture disappear – and, more importantly, in poet Nise Malange’s words, “how do we remake workers’ culture” in today’s struggles?

Cultural locals

Despite the paucity of detailed research, we know the story of what happened to worker culture in broad outline. Union ‘cultural locals’ had sprung up relatively spontaneously in many areas, particularly in KwaZulu-Natal and the East Rand, during the 1970s and early 1980s.

A network of locals was built and fostered by shop stewards as a powerful organising tool, and embraced by members as that and much more. Discovering their creativity through organising, workers saw they could own and unleash it to remake their world. A vital part of that was their process – collaboration in creative collectives of fellow workers, what revolutionary artist Thami Mnyele in 1982 called the connection to “the river of life”.

Those collective processes of learning creativity survive. Veteran struggle poet James Matthews told New Frame about using the same methods today in schools and workers’ classes at the University of the Western Cape. “I’d write a line and then ask them to create more lines, working in groups.” A collective writing process such as this, he says, gives the writers an awareness of working together and shared experiences and ideas. “You might think the results would be just bits and pieces, but in the end, these lines they created, they fitted perfectly together. And they fitted because we were working together.”

The Federation of South African Trade Unions, founded in 1979, was both an umbrella and an engine for the cultural locals. The federation, with other elements of organised labour, transformed into Cosatu in 1985, and established a cultural desk the same year.

But sustaining culture as part of the federation’s core business proved difficult. Union cultural locals had regularly engaged in joint activities with the United Democratic Front, but attempts to forge a more regulated national organisation in collaboration with alliance partners under Cosatu’s cultural desk added a bureaucratic burden at a time when trade unionists were already fully occupied battling repression, bannings and murderous attacks.

At the Culture in Another South Africa conference in Amsterdam in 1987, voices of ANC structures based outside the country dominated. Subsequently, responsibility for aligning cultural policy at home and abroad began to move to the ANC’s department of arts and culture, which had been established in 1983 under Barbara Masekela, working out of Lusaka and London.

Ideological debates

Ideological burdens were adding to organisational ones. In 1989, ANC activist and jurist Albie Sachs published a paper called Preparing Ourselves for Freedom, arguing for a ban on the term “culture as a weapon of struggle”. It was time, he wrote, to start writing love songs again. (To which poet Keorapetse Kgositsile indirectly responded in Red Song, written earlier but published in 2003: “Need I remind anybody again that armed struggle is an act of love?”) As negotiations with the apartheid regime about transition proceeded apace towards elections, compromises emerged and priorities changed.

In 1990, the Federation of South African Cultural Organisations was established: an initiative inside South Africa to debate and develop the new national cultural policy and transform parastatals such as the state theatres. Although the ANC’s department of arts and culture was initially supportive, the federation’s refusal to align exclusively with the ANC and its rejection of commercially oriented arts paradigms led to clashes. By 1992, it had fragmented, its positions sidelined.

Masekela’s first big address on returning to South Africa was to the steel and engineering employers’ federation. The visual language of the ANC election campaign was outsourced to major international advertising agencies and monopoly printing houses, not the artists and printers of struggle. Progressive international donors, assuming that support for people’s culture would come from the new ANC government, started tapering off their contributions.

But in shaping that new government, the ANC brokered away what it considered less strategic areas to minority parties – arts and culture, in a ministry also including science and technology, went to the Inkatha Freedom Party. At the book fair, poet and scholar Ari Sitas summed it up: “Culture was handed to Inkatha and creativity to the market.”

The market

And as apartheid censorship and the cultural boycott ended, a tsunami of globalised, commoditised culture crashed over a largely unprepared South Africa. As the country became a “normal” capitalist democracy, hegemonic, Eurocentric and market-oriented cultural definitions were reimposed. The creativity of working people was redefined as “craft” or “propaganda”, certainly not art – contemporary scholarship on the history of South African choral music, for example, rarely even mentions mzabalazo.

“ The world changes, revolutionaries die / And the children forget / The ghetto is our first love / And our dreams are drenched in gold… ” (Thandiswa Mazwai, Nizalwa Ngobani, 2006)

Cultural commodities created for workers abound today: both deliberately designed consumerist distractions and (sometimes) well-meaning reinterpretations from outside. “Now, I will speak and they will write,” said one participant at the book fair. “What I say as a black South African woman, they appropriate. The knowledge they want to consume is bleached so it doesn’t make them uncomfortable.”

All these definitions rub out the idea that culture can be made by workers. They imply workers are born only to consume commodities created elsewhere, and reproduce the innovations of others at work – a view reminiscent of the African craft curriculum under Bantu education.

Reasserting worker culture, argued scholar Bheki Peterson at the book fair, is one of the key acts of decolonisation. Peterson highlighted the exclusion of worker art by academies and urged the need to reassert its existence, history and value, as well as its distinctive canon and aesthetics.

This entails finding or creating spaces in which workers can create, display and perform – spaces that recall those occupied and defended by worker artists in the 1970s and 1980s, from the people’s parks to the K-Team choir and Cape Town’s MAPP (Music Action for People’s Power) college. The creation of these kinds of spaces today could challenge the schisms into discrete, marketable genres – or into the binary of maker versus consumer that currently dominates arts discourse in South Africa.

Swedish worker-poet Jenny Wrangborg (a former chair of that country’s Association of Working Class Writers) described encountering similar schisms in Sweden. She could find publishers for her poetry about life as a kitchen worker, “but they told me it stops being literature when it starts demanding change, and they could not publish that”. Progressive publishing initiatives are also central to both writers’ and readers’ access. Writer Jolyn Phillips, born into the Gansbaai fishing community, recalled her mother warning: “Don’t expect to sell too many books here. If I have to choose between buying your book and buying bread…” But even where there’s money to buy bread, the dominant use of English erodes accessibility: Qabula wrote and performed in isiZulu.

Spaces to create and learn collectively that validate the experiences of working lives build both examples of practice and the confidence to pick up a pen. If we can create those, the new Qabulas will come. Matthews recalled how, a few years after his course, one of the workers he had schooled in collective writing “sees me in the street, and tells me: ‘Mr Matthews, I’m now writing poetry too. I’m a poet.’”