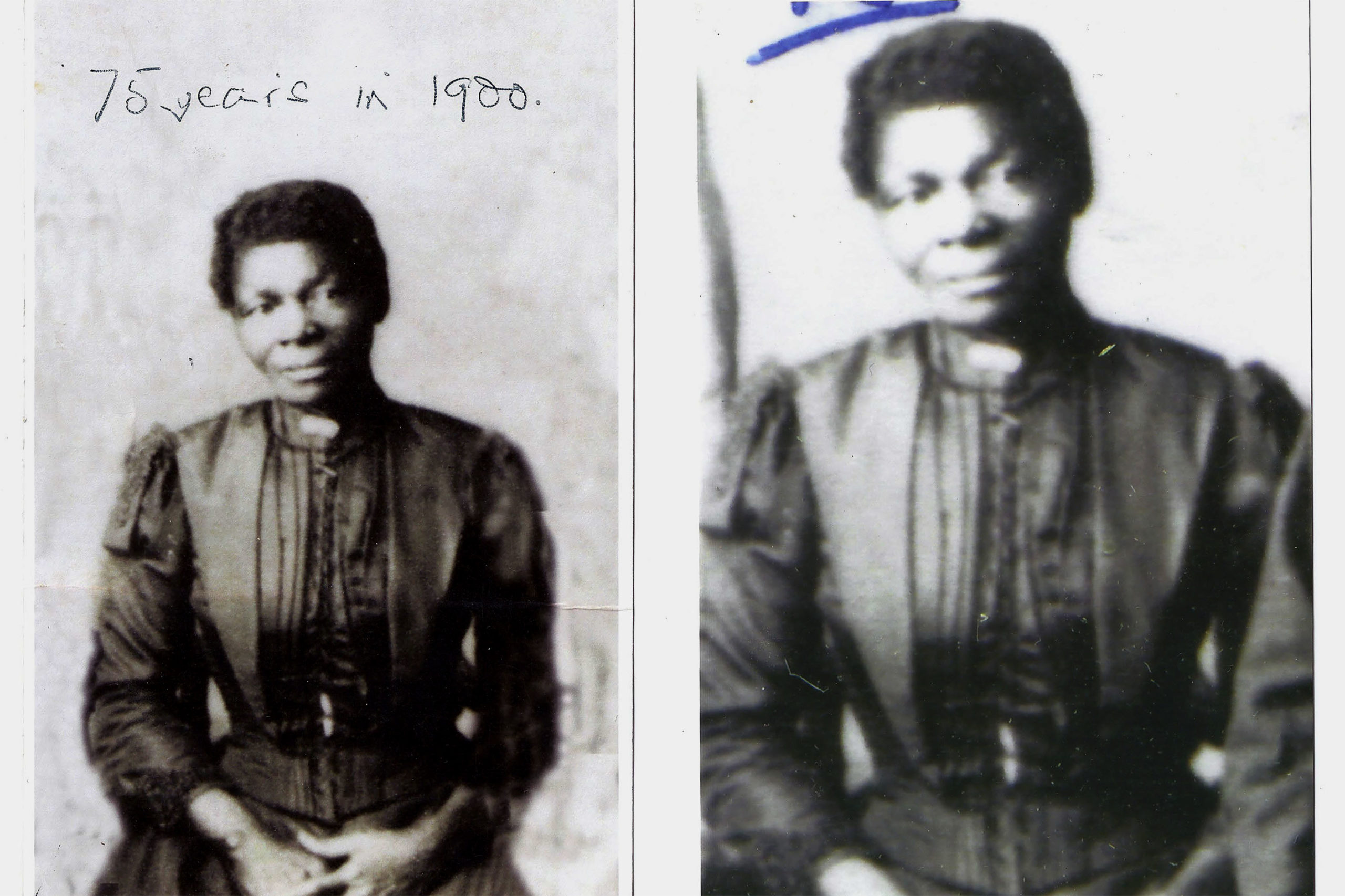

Rachel Thoka, mystery slave and forgotten heroine

She was brought to the Cape in chains, then became a Boer hero before turning into an activist for the early ANC. But where did she come from? Her grandson spent a lifetime trying to find out.

Author:

25 October 2021

Paul Mosaka, a successful funeral home owner from Johannesburg, stood up to address the small family gathering on the eve of an important departure in the late 1950s. Mosaka turned to the man of the moment, Isaac Thoka, the one the family affectionately called Bookworm.

“My son, it is your duty to fulfil the family wishes,” Thoka would recall Mosaka saying. “That of finding Rachel’s origin. Ghana may be the country from which Rachel was taken by the slave traders and sold in the Cape.”

The businessman continued, “Rachel was a noble woman who fought for her people’s rights and all of us are proud of her and should be honoured that one day you write a book about her life.”

With that, Mosaka handed Isaac an envelope that held £25 and the following morning he was on his way to Ghana to take up a teaching job. Ahead of him was a journey he would continue to travel until his dying days.

This journey would lead him to the beaches of Accra in Ghana, where, as he helped the fishers pull in their nets, he’d stare into their faces hoping to recognise the ghost of his grandmother, perhaps in their eyes or in the contours of their faces. Isaac recollects that in a former slave dungeon along the Ghanaian coast, he would take in the stench of stale human sweat and wonder if his grandmother was once held in the dark, cramped place.

Later he would travel to Mozambique, again trying to find a trace of his grandmother. To her family and academics, Rachel Thoka was an enigma. She was a slave girl who became a hero to the Boers, then in deep old age she turned into an activist while rubbing shoulders with the founding fathers of the ANC.

In time, Isaac would write about his grandmother’s incredible long life. He would fill his unpublished manuscript with the stories Rachel told his father, Crawford, and himself, when he was still just a young boy.

Sold into slavery

His manuscript begins with a young girl with an unusual name. “She was called Emu and she lived in a village close to the sea, from where she would watch the ships with their tall masks follow the coastline,” he wrote.

Although Isaac had long debated just where his grandmother came from, by the time he began writing his manuscript, he had settled on Rachel having come from somewhere along the west coast of Africa.

He tells the story of a young girl living an idyllic life. Her “tribe”, the Akhahkans as Isaac called them, were prosperous and ruled by a benevolent king.

Isaac’s account of Rachel’s early life is detailed. He includes the names of villagers and their conversations. It is unclear, says historian Cecilia Kruger, who worked with Isaac on his manuscript, if some of what he wrote he fictionalised, or if this detail was exclusively drawn from Rachel’s memory.

Then, early one morning, it all changed. The white men who sailed in those passing ships came ashore and attacked their village. In the skirmish, Emu and other children were grabbed and taken to the ship. There, they were bound two by two, with heavy chains wrapped around their necks. In old age when telling of her time as a slave, it is said Rachel would rub her neck where an abscess caused by those rusted chains had left a visible scar.

Rachel described being kept below deck, where it was so cramped the children sat with their knees bent. “The white men threw the captives pieces of meat, fish, fruits or whatever they collected from the islands where they stopped,” Isaac wrote.

If Rachel did come from West Africa, her journey south would have been an unusual one. Most slaves who came to South Africa did so via the east coast of Africa, says historian and slavery expert Mogamat Kammie Kamedien.

Related article:

“We know during the early stages [of European colonisation] at the time of Jan van Riebeeck there were slaves from West Africa. Then it switched over to Indonesia, India, Sri Lanka and then finally to Mozambique and Madagascar,” he explains.

But there is a possible explanation as to how Rachel might have arrived in Cape Town, and it would have involved a black market within the global slave economy. Slaves were expensive in the Cape colony, so there was money to be made.

“There was always talk over the years that ship’s captains would smuggle people from unknown areas into the country,” says Kamedien. Rachel had no idea how long she was at sea. When she and the other enslaved people landed in Cape Town, they were quickly auctioned off. No documentation remains of this sale.

On the Great Trek

The family who bought her were a well-off Afrikaner family called the Griesels. Mrs Griesel had wanted a slave girl to look after her children. The slave girl was given a set of hand-me-down clothes and a new name taken from the Bible.

On the Griesels’ farm, Rachel would look after the children and work in the kitchen. She quickly learned Dutch and would pick up on the gossip of what was happening in the farming district and the Cape Colony.

One bit of news that was to change Rachel’s life drastically was met initially with little fanfare. On 1 January 1834, slaves were freed in the Cape Colony. “Do you know Rachel that you are now free and no more a slave?” a slave called Tolly is quoted as saying in the manuscript.

“I am not going anywhere. I have no other people than the Griesels,” she replied. The emancipation of the slaves did have another effect and Rachel began overhearing about it from the farmers who sat on the Griesels’ stoep.

The Boers, in part unhappy with the British decision to free the slaves, wanted to leave and head to the so-called promised land. It’s ironic that the Boers saw their move in terms of Exodus, the movement of the enslaved out of Egypt while the main motivation for their action was to keep their slaves.

This was the start of the Great Trek, and Rachel would join the Griesels as an unpaid servant in a wagon column heading north. In the coming months, Rachel would be a silent witness to some of the biggest events of the Great Trek. She calmed the children as a Ndebele ipi threw itself against their laager at the battle of Vegkop.

At the foot of the Drakensberg, she listened to preacher Sarel Cilliers encourage the Boers to cross the mountain range into what was to become Natal. One of those listening was Piet Retief, who Rachel claimed had the “voice of a crow”. Then, on the bank of the Bloukrans River, Rachel committed the act for which she would forever be remembered.

Heroic deeds

The party of Boers had camped at this spot while waiting for the return of Retief, who had headed to the royal capital to negotiate the sale of land with Zulu king Dingane kaSenzangakhona Zulu. Dingane killed Retief and sent amabutho in search of the Boer parties.

When amabutho attacked, Rachel said the men were not in camp as they had gone hunting buffalo. “I could actually see the feet of the Zulus as I sat motionless, blending with the wood beside the wheel of the wagon as I pretended to be dead,” Isaac would record his grandmother saying.

It was then she noticed a three-year-old boy covered in blood under the body of his mother. She grabbed him and ran past the Zulu regiment. Rachel and the child hid in a donga.

More than 500 men, women and children died that day.

The news of Rachel’s heroic deeds travelled fast. In another Zulu attack at Mooiriver, shortly after Bloukrans, Rachel received an assegai wound to her hand. From then on she was known as Mooiriver. What was left of Rachel’s party trekked over the Drakensberg to safety. Some parts of Rachel’s story aren’t captured, such as how she became the servant to another family, and it is unclear what happened to the Griesels. It is also unclear when Rachel was emancipated and if she was given the choice to leave. Although it appears her life continued as before.

Related article:

Historian Estelle Pretorius checked the records of those who died at Bloukrans and there is no mention of the Griesels. Rachel for a while settled in Potchefstroom where she ended up in the employ of the future president of the Transvaal, Paul Kruger.

There she met and married her first husband, pastor Julie Mpinda. Not long afterwards, they headed to the Free State and, by 1871, Rachel was living in Bloemfontein, where she would remain for the rest of her long life.

In 1900, she watched the British troops march into the Free State capital, and when the South African war ended, she and Mpinda moved to Waaihoek, Bloemfontein’s first Black township. A couple of years later, Mpinda died and Rachel then married a man named Abram Thoka.

In Waaihoek, Rachel, then said to be close to 90 years old, found a new calling. She became an activist. Her sons James, Bunny and Crawford were already involved in politics, having become members of the South African Native National Congress (SANNC), which was eventually to evolve into the ANC.

In 1913, a pass system was introduced in Bloemfontein for African people and it incensed Rachel. A group of women and a delegation from the SANNC came to see her. They pleaded with her to lead the women of Waaihoek in a campaign against the pass system. Rachel agreed. With the support of Sol T Plaatje, the general secretary of the SANNC, Rachel led marches and organised petitions.

“I thought the slave chain had been removed from my neck now that I am no more a slave,” she is reported to have said. Once, she led a march to the police station in Bloemfontein and none of the officers dared arrest the heroine of Bloukrans. But the pass system was to stay.

Honouring Rachel’s story

In the years that followed, there was renewed interest in Rachel’s story. Journalists came and interviewed her, and historians and anthropologists picked her memory looking for clues to her origin. She was the darling of both the white and Black people of Bloemfontein.

Jannie Schoeman, the great-grandson of the Voortrekker boy Rachel saved at Bloukrans, would visit her. One year it was decided that as part of the annual SANNC conference, Rachel would be honoured in a surprise event. Plaatje would write a script to a play that highlighted Rachel’s life and heroic deeds. Her son Crawford would compose the music. It was said the cast was chosen carefully.

Peter Phahlane, a big man dressed in a khaki tunic and veldt hat, would be her former slave owner Sarel Griesel. Willie Stephans portrayed Piet Retief. The part of Rachel would be played by the short and dark Mita Kotsi. On the night, the hall was crowded. Members of the SANNC sat with white council members and journalists reported on the event.

Related article:

After the play, Plaatje introduced Rachel. The audience erupted into shouts of Mooiriver, Mooiriver, Mooiriver. With tears in her eyes, Rachel thanked the crowd. “The tears I am shedding are those of joy of making me remember what happened to us during those hard times in the Trek,” she told the audience.

Rachel died on 26 September 1940. Her death certificate said she was 113 years old. By then her children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren were scattered across the country. It was after he had retired that Isaac decided to fulfil his promise to Mosaka and write a book about his grandmother.

But it would be hard going

Related article:

“He first came to me in 2002 when he was trying to find funding to publish his book. The problem was that he just couldn’t finish it. It was [as] if he was afraid,” says Kruger.

He died leaving an unfinished manuscript. Kruger still hopes that Rachel’s story will be told, if Isaac’s manuscript can be turned into a book. For Kamedien, Rachel’s account is unique because there are few first-person slave narratives that survive in South Africa.

With new technology, Isaac’s burning question that drew him to Ghana all those years ago may one day be answered. DNA could perhaps solve just where a little girl called Emu began her incredible journey all that time ago.