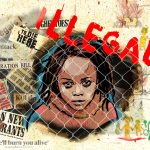

Quest for South African citizenship

After a decade of enduring xenophobic victimisation in her country of birth, a court ruling has ordered home affairs to grant Mary Mwale and her family South African citizenship.

Author:

10 December 2018

Watching the neighbours’ children playing across the road, Mary Mwale, 55, seemed at ease while resting her arms on the front gate to the yard of her family’s small corner house in Katlehong, east of Johannesburg. Less than 24 hours earlier, she had heard that her 10-year wait to be declared a South African citizen was over.

“We’re so so happy. I cannot even tell you. We’re very hopeful things will get better for us now,” Mwale said in the living room where she grew up and her parents lived before they left South Africa. With the help of Lawyers for Human Rights, Mwale and her family were finally victorious, with the North Gauteng High Court ruling in their favour on 28 November.

The court declared Mwale a South African citizen and ordered the department of home affairs to lift the blockage on her ID number, issue her with a South African ID, and process and issue birth certificates for her four children and two grandchildren.

Related article:

The family’s newfound happiness and hope for a new future was preceded by years of stress, anger, confusion and depression. “You are always isolated. You can’t even join funeral schemes. There is nothing you can do,” Mwale said, adding the family had experienced problems opening bank accounts, finding work and getting the grandchildren into school.

A family in limbo

Mwale moved from Katlehong to Blantyre in Malawi with her South African-born mother and Malawian-born father when she was 16. In her affidavit, she explained that she believed she had left South Africa on her mother’s passport because her birth was never registered in South Africa.

Settling into her new life in Malawi, Mwale met her husband and had four children with him. Her mother died in 1998 while on a visit to South Africa. With the help of a local chief, Mwale obtained a Malawian passport to attend the funeral.

Four years later, her husband died of pneumonia. Her relationship with her husband’s family quickly deteriorated because of a dispute over his property, which he left to her. She sold the property in 2007 and returned to South Africa through the Musina border using her Malawian passport.

She settled back into her parents’ home in Katlehong, where she was still familiar with old neighbours. In 2008 and 2009, she made three attempts to apply for late birth registration and a South African ID to restart her life in South Africa. But for the next 10 years, she would endure the same discrimination other African migrants face, but in the country in which she was born.

Unhomely affairs

Sitting on the worn and cracking black leather couch in the living room, Mwale recounted the problems the family had faced since returning to South Africa and living without IDs. “When the police found [my children without IDs] … they would sometimes keep them for the whole day. My first-born son was arrested and taken to Lindela, and even deported,” Mwale said.

“I was angry … You know, sometimes I couldn’t sleep at night. At a certain stage, I even reached a point to commit suicide, but I changed my mind when I thought about my children,” Mwale said. She described how she felt confused and frightened through her many interactions with home affairs officials, including the time she was detained and accused of lying and trying to defraud the government.

Related article:

“The language they used at home affairs, they used to say, ‘You are a foreigner. You want to pretend that you are a South African,” Mwale said. Her daughter, Patience Chombo, 34, said she was often called “lekwerekwere” and other xenophobic slurs. “Even here in the location, people used to call us foreigner. Even to find a job, for us it is hard. For my child, it is hard to find a school … Sometimes we work for free and they don’t pay us because we are foreigners,” she said.

Mwale shares the four bedroom house with three of her children and her two grandchildren. None of them are employed and they rely on often precarious and low-paying piece jobs to get by. Her son, Daniel, who lives nearby, is the only member of the family who has work.

Mwale and Chombo said their situation wasn’t unique and that there were many other families battling home affairs to solve identity and citizenship issues. “They saved our lives,” Mwale said referring to the help they got from Lawyers for Human Rights. She urged people in precarious situations to seek out help.