Queer ancestor Kewpie created her own freedom

A new photographic exhibition celebrating the life of drag artist and hairdresser Kewpie in District Six during apartheid is like ‘meeting a queer ancestor for the first time’.

Author:

4 June 2019

In the photographs of Kewpie living her life, queerness exists outside of the constant flow of triggering headlines. Over 100 pictures at the Kewpie: Daughter of District Six exhibition currently showing at the Market Theatre Photo Workshop in Newtown, Johannesburg, invite us into the life of Kewpie, a celebrated queer figure, drag artist and hairdresser in apartheid South Africa’s District Six. At the exhibition launch on 16 May 2019, coinciding with the International Day Against Homophobia & Transphobia, surrounded by other queer people and lavishly dressed in the invite’s “legendary” theme, I allowed myself to shrug off the heaviness and constant anxiety of being visibly queer in public, held my partner’s hand and simply fell into the beauty and joy that is us.

The bold and the beautifully outrageous

“I’m naturally just me.

People can’t say I’m a man,

They can’t say I’m a woman.”

These words are imprinted on a soft pink wall under an image of a lipsticked Kewpie wearing a flapper dress, pearls and feathers. Gaze flirting with the camera, she pouts, showing off her lipstick.

The freedom to be naturally yourself can be both a hard-won celebration and terribly lonely, with a range of experiences in between. In a world where being heterosexual and identifying with one of only two genders continues to dominate ideas about how we should be, “I’m just naturally me” is a radical statement. More than a simple mantra, it brims with the politics of resistance.

The histories of people like Kewpie are rarely in the public eye. Mostly we hear about queer people being violated and killed as a result of expressing their identities. Being South African, violence is the common language over which queer people form bonds of trauma.

But the Kewpie: Daughter of District Six exhibition carries us through a history we never knew. Compiled in collaboration with the Gay and Lesbian Archive (GALA), the District Six Museum and and the Market Photo Workshop and funded by the Norwegian Embassy in South Africa, the collection acts as a time capsule.

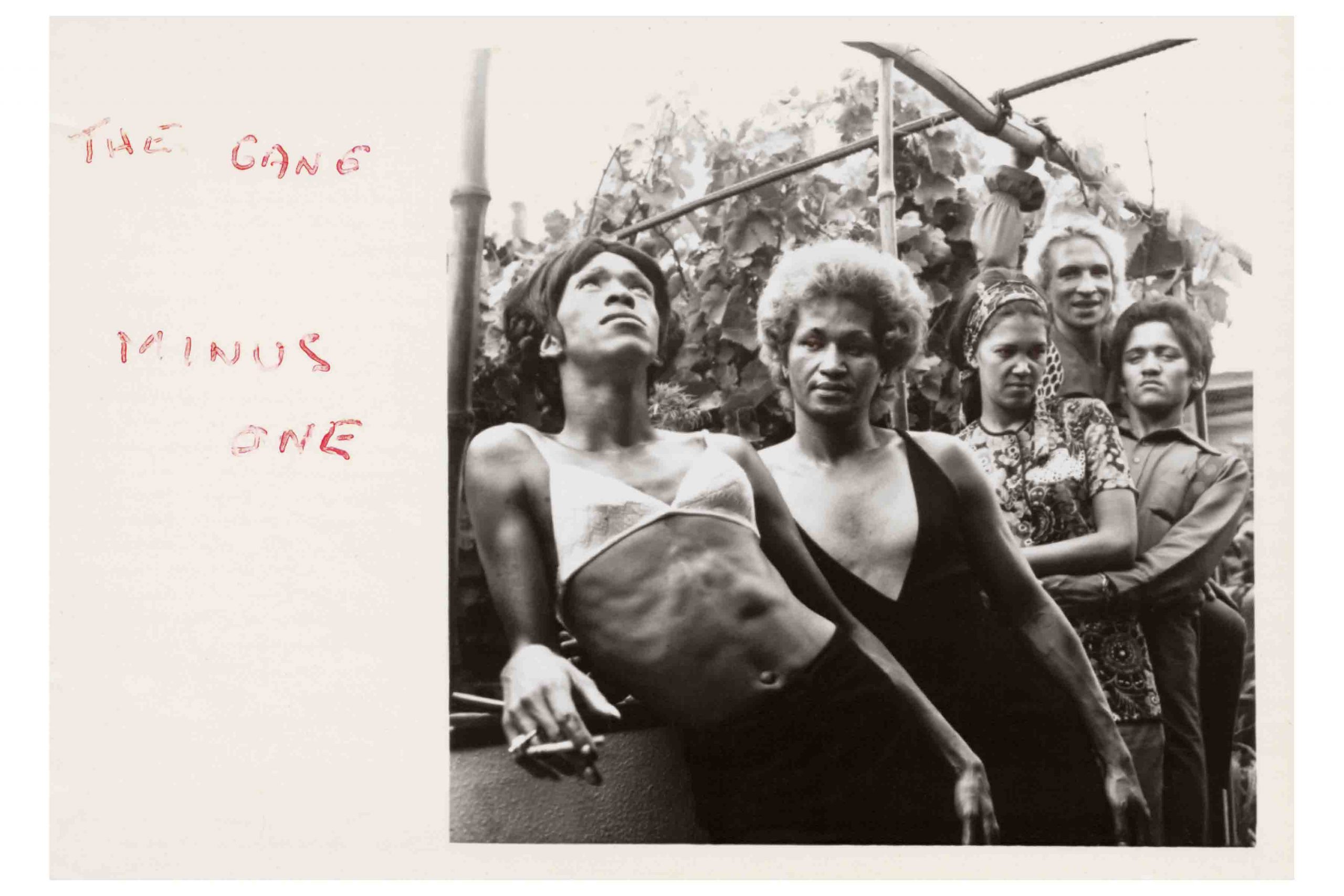

Photographed mostly by friends and sometimes by more professional photographers, these images give us a glimpse into Kewpie’s family life, and into the time she spent with friends and neighbours at bars and beaches and in her two salons, Yugene’s Hairtique and Salon Kewpie, where they would mix their own hair dyes using tea leaves, vinegar and henna. We are taken through her drag days, where she performed at District Six’s Ambassador Club under the name Doris Day and later Capucine, inspired by the French actress and model.

I felt honoured to be taking in this vast life, meeting a queer ancestor for the first time. As director of GALA Archives Keval Harie says, the exhibition is important “particularly for young, black, queer people in South Africa, because it provides us with a sense of visibility, and visibility is important in knowing we have always existed”.

Black queer futures and documenting ourselves

“I was just me. And I used to dance and sing around, and people came to love me for being that energetic person.”

“Black queer possibilities look like defining things for ourselves,” said gender activist Letlhogonolo Mokgoroane in his address at the 2018 Simon Nkoli Memorial Lecture, which honours Nkoli’s contributions to a life of LGBTIQA+ activism. “We should really ask ourselves: what does black queer futures look like? The answer to the question will be different for each person, because queer is not monolithic and that is its beauty. Black queer futures, for me, entails creating our own narratives. It is doing the work of intentional archiving our histories, our present, our joy – whatever they may look like.”

This is something to take with us as we enter spaces of remembrance and move to create our own histories. Kewpie did this work intentionally, shaping her life as she wanted. When talking about personal narratives of identity, fluidity and desire, scholar Ruth Ramsden-Karelse described the Kewpie collection as “vast, complex and contradictory in ways. She worked to create her own spaces of freedom within restriction.”

Young queer people can see themselves in many of these images: documentation allows us to see love, community and find significance in the insignificance of queer people simply being themselves. Once we look behind us, we see the connections in the lives we often feel we live in isolation. In a history almost erased, this archive represents not only Kewpie’s material history, but also acts as a reclamation of space and existence. It is an intentional inscription of ourselves.

“Everything that we can do to erase the erasure and to give voice where there was silence, that’s what we’re doing with this archival work every day,” writes gender scholar KJ Rawson. Archiving is political. It allows those of us who are purposefully sidelined and silenced to realise we are worthy.

From individuality to community

“That is how they adopted you with that love of being you. Not as being queer, that moffie or that gay. But they came to love you as that human being.”

With her fluid gender identity, Kewpie allowed me to see parts of myself while still seeing her as she was, filled with love, community and purpose. “Kewpie’s legacy raises important and necessary questions for the LGBTIQ+ community in terms of issues of identity,” Harie says. “We need to move beyond binary approaches of identity and support communities, particularly the trans community, and focus on being gender affirming. That is the power of Kewpie’s story.”

Peeking into her life, I felt inspired to find more of our queer icons. Our histories need to be continuously honoured in this way. We owe our history to those whose names we are not yet familiar with – all of whom are worthy of being archived.

The Kewpie: Daughter of District Six exhibition is running until 31 July 2019 in both gallery spaces at the Market Photo Workshop in Newtown, Johannesburg.