Betebuciko eSwatini bayala kujutjwa umlomo

Loku lisha lela live, badvwebi bemifanekiso, bacophi bemafilimu nalabanye labenta umsebenti wetebuciko batsi angeke bayekele kukhombisa lobunuku nebudlova lobentiwa nguhulumende.

Author:

26 April 2022

r cities are in the pipeline, while it has also been broadcast by the SABC’s investigative programme, Cutting Edge.

The Unthinkable features disturbing accounts of the violence inflicted on people and the unimaginable pain they endured, which is what inspired the title. For example, says producer and director Comfort Ndzinisa, 36, during one protest soldiers placed burning matter on a man’s body, searing his skin.

“I’ve never seen something like that,” says Ndzinisa. “The soldiers entangled hot tyre wires around his body. This is such an unthinkable act.”

The documentary was produced in partnership with the eSwatini Solidarity Fund, an organisation of local and international volunteers and sympathisers set up to offer financial and psychosocial support to the many who were shot and sustained injuries of varying degrees.

But it was unplanned. Filming began by chance when Ndzinisa, a high school science teacher who usually films for “fun”, was asked by a friend from the fund to edit some footage.

“I asked the friend to do a retake because the initial interview was not filmed [in] landscape [format],” he says. He then joined the fund’s team on the ground to film and “from there the footage got bigger and bigger. There were more people involved, more organisations involved. It was sort of an archive. It was not necessarily meant to reach the magnitude that it did.”

A stark reminder

A university student, Tibusiso Mdluli, 22, one of the fund’s field volunteers, explains that the documentary crucially highlights the brutality of the security forces. For example, she recalls that at the end of 2019, when university students were protesting for allowances, “there were students beaten [by police] while wearing towels, coming from bathing”.

Ndzinisa reminds one that the struggle for freedom and democratic reforms in eSwatini is nothing new. “It is not the first time the forces have been unleashed on people, it is not the first time there’s been unrests, except that it has taken a much more noticeable scale. It is intense.”

Mdluli emphasises that it is important for emaSwati to document their experiences. “Our struggles have been sort of erased. I get the sense that people in the international community do not know so much about Swaziland.”

Another field volunteer with the fund, Gugulethu Makhanya, 40, who was instrumental in the documentary’s conceptualisation, says the filmmakers hoped to put faces to the injured as well as the families of the many who died.

“We hope people can have an insight into what is exactly happening. It is very important for the outside world to know and see the atrocities,” says Makhanya.

To date, the number of those who died and those injured is still debated, mainly because of censorship and the inability to meet some of the victims. But for Ndzinisa, the vivid reminder of the violence captured in the documentary renders the actual numbers moot.

“It vaporises the argument – you can’t argue about the numbers anymore. Whether it is five people or 100, it looks very bad on the government,” he says.

“If truth be told, it really is protest art. Is it not just like the paintings that artists are doing?” adds Makhanya.

Finger on the pulse

Fashion designer and artist Khulekani Msweli, 37, from Vuvulane, a sugar cane-growing region in eSwatini, says the role of artists in the country is undervalued, yet they “play a very critical role in social commentary, in speaking truth to power and … offering a mirror to citizens of any country”.

“Artists tend to have the pulse of society and have a way of articulating it … to record and preserve those moments,” he says.

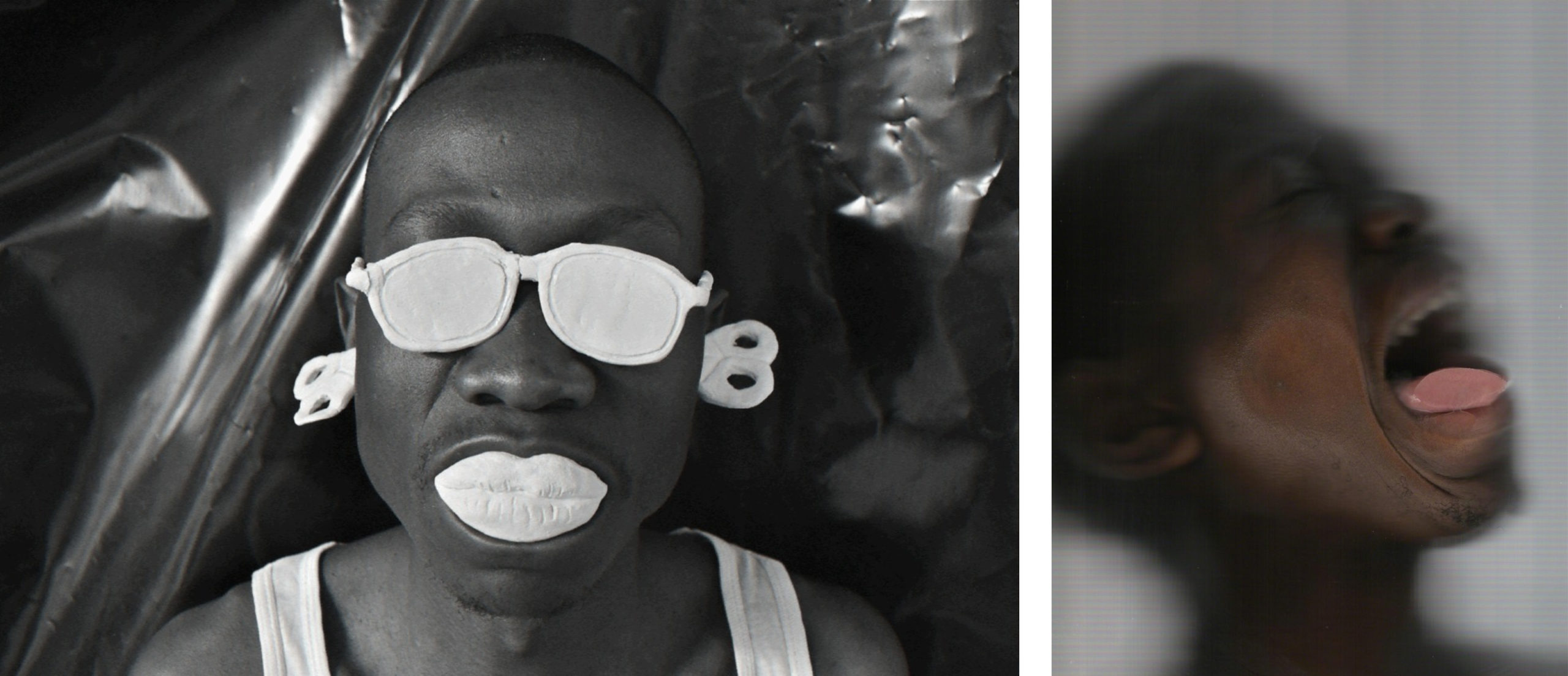

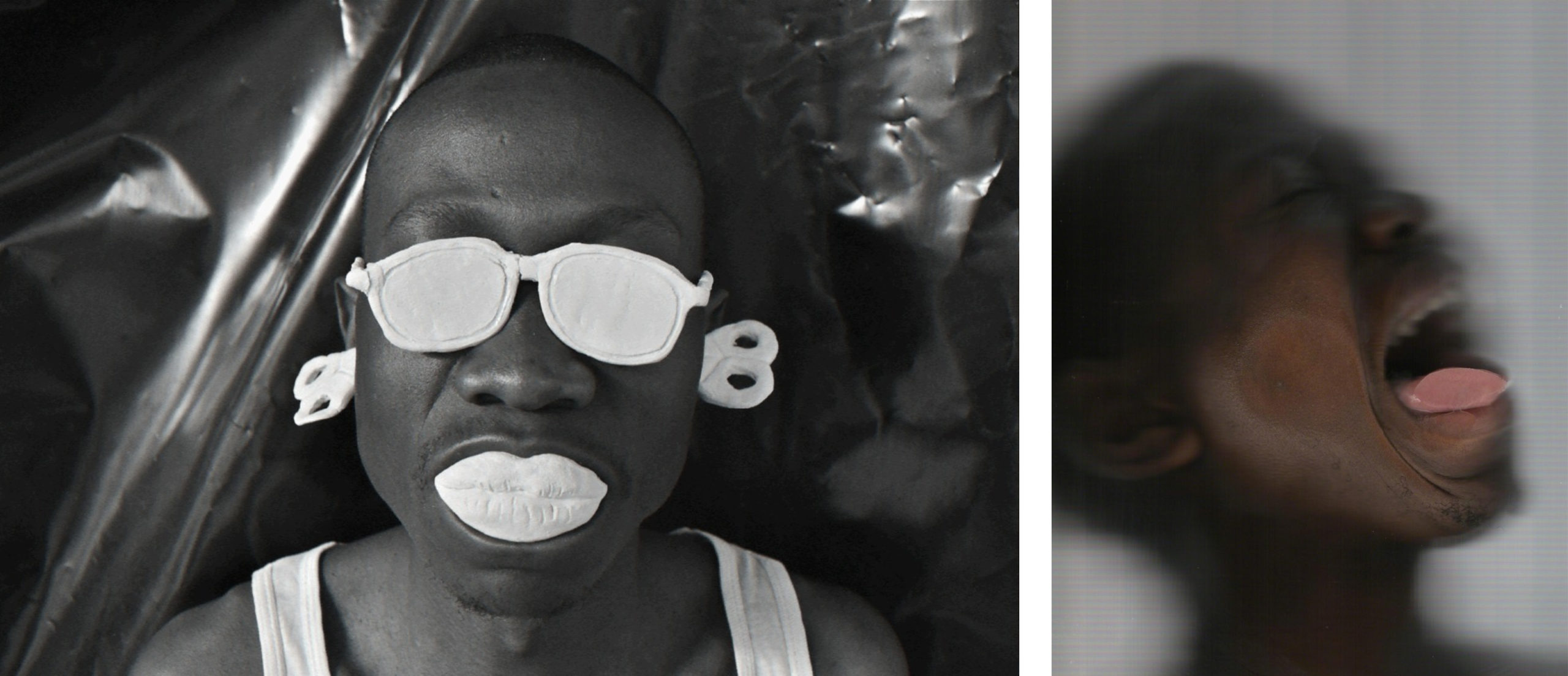

Msweli has crafted many pieces that comment on the regime. One such artwork is the self-portrait See No Evil, Hear No Evil, Speak No Evil, in which Msweli has covered his eyes, ears and mouth, speaking to how it silences radical thoughts and expressions.

“A lot of emaSwati feel gagged. If they speak their truth or speak up to power, they could end up in prison, or they could end up maybe tortured by the police,” Msweli says. “The more we keep on bottling up these issues, we end up being faced with a situation which we are now facing in 2021, where the citizens eventually erupt.”

Those who dare to challenge the regime’s status quo pay a heavy price, he says, but “someone has to say something. We can’t all be silenced [in expressing] our own thoughts through artistic forms”.

Msweli reflected on how silence can end up in death with a 2017 photographic work titled Silence I, in which his face with a wide-open mouth is pressed against a surface.

Quietly speaking out

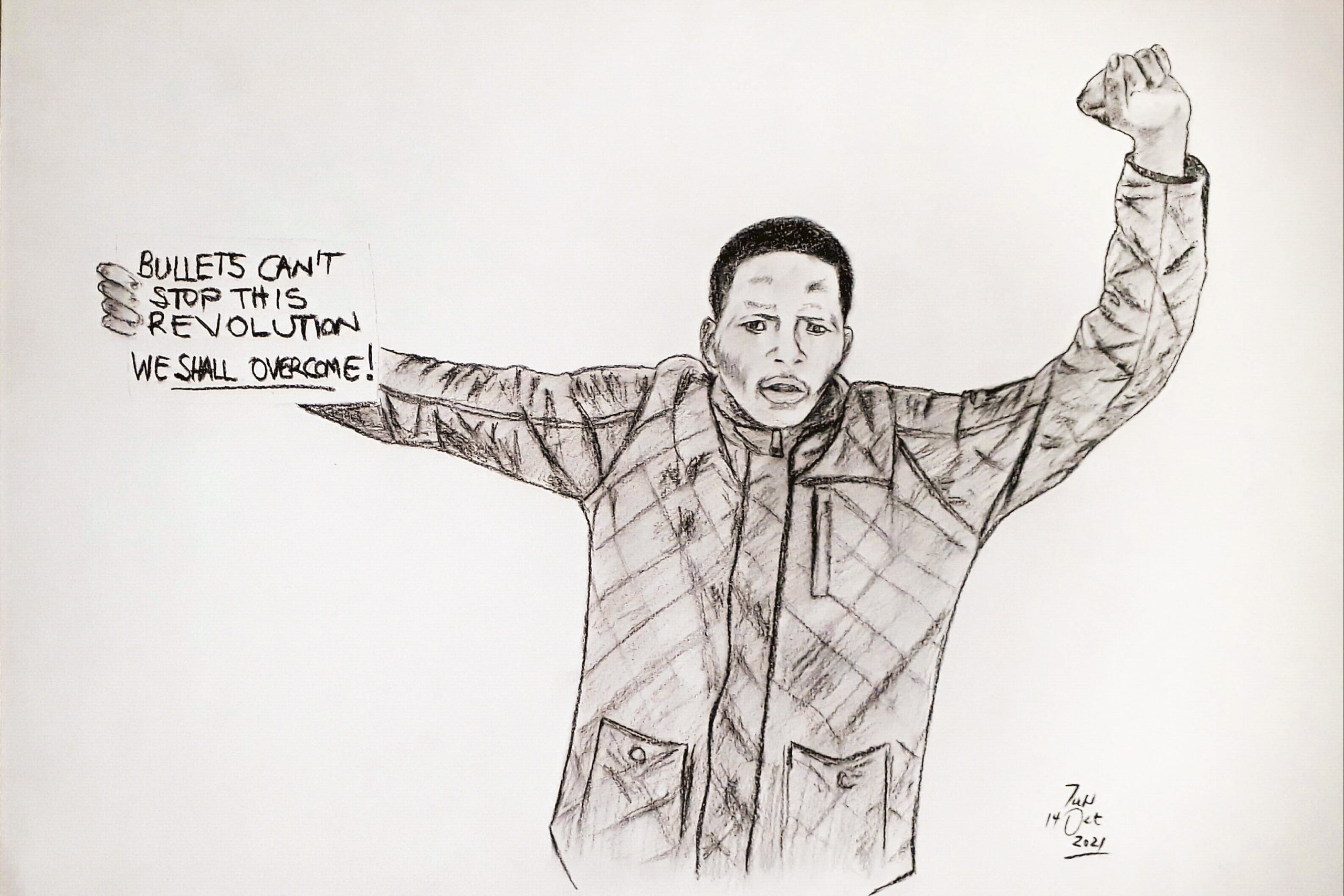

Another artist who says the population is being silenced is Tutu Mkhabela, 42, who comes from the rural area of kuMalindza. Mkhabela is self-taught, and his work is mostly done in graphite and pencil. “I was born in a family of artists. I grew up looking at my elder brothers’ sketches and I was like this is something I’d like to do,” he says.

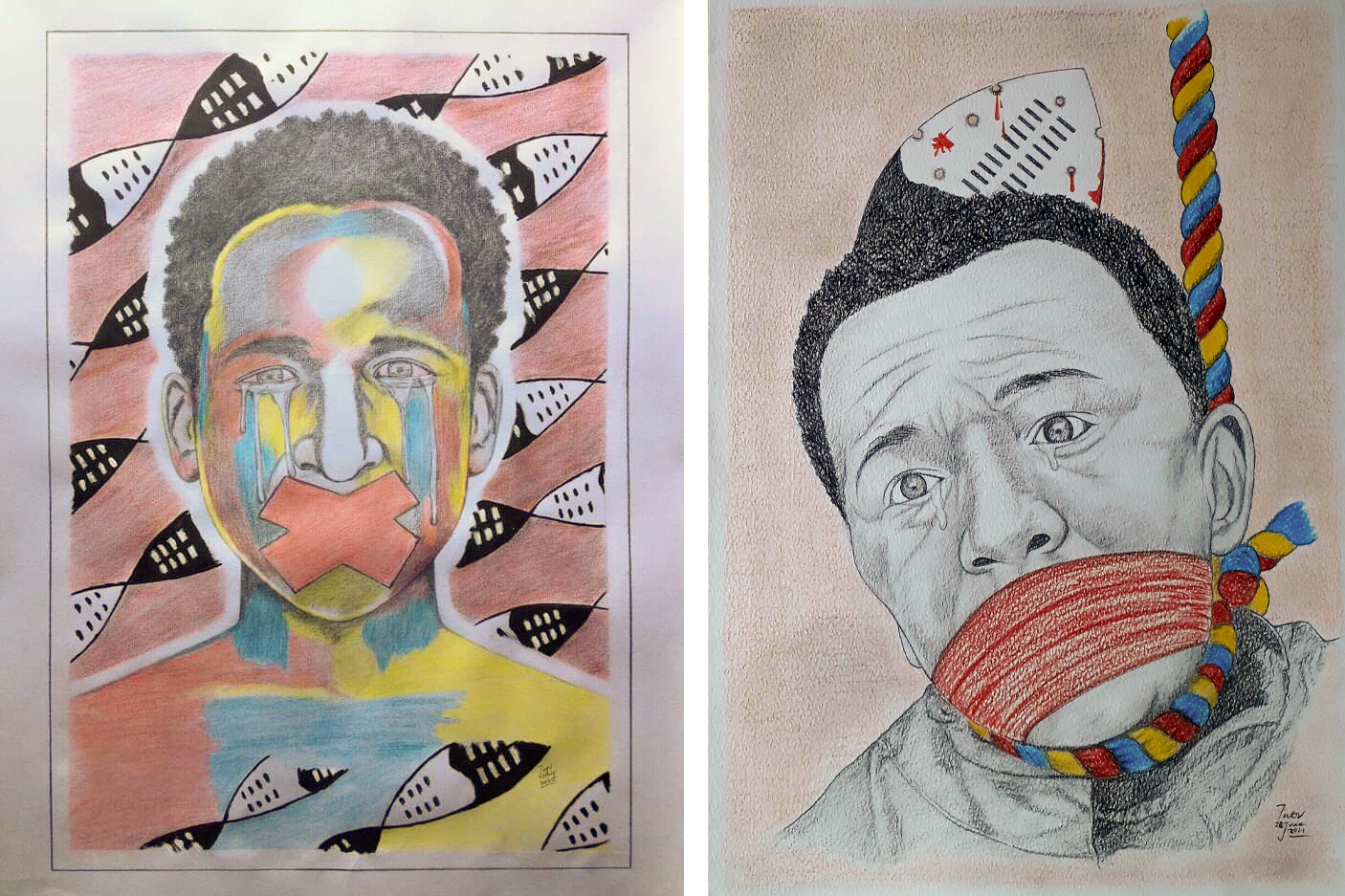

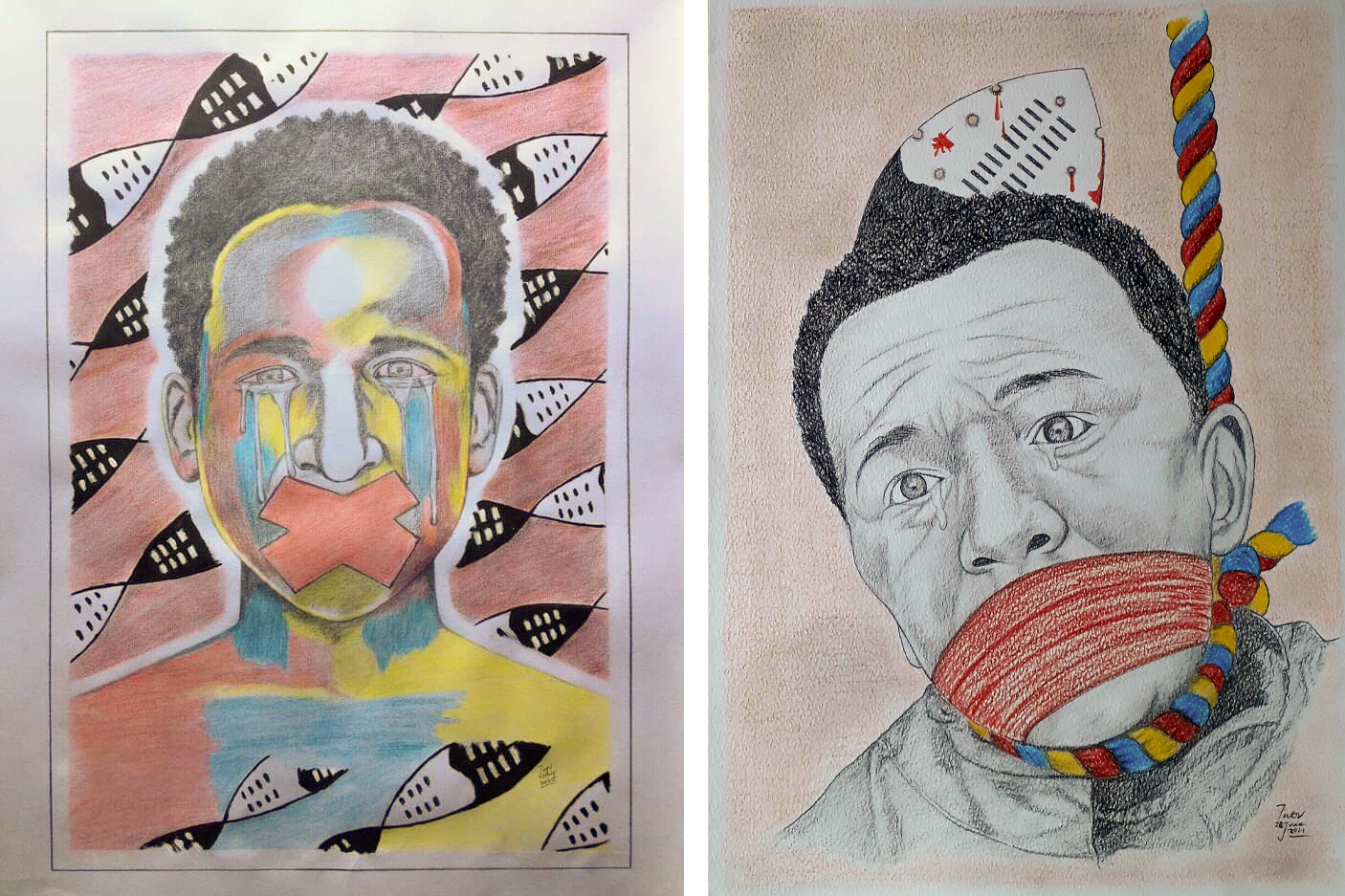

Like Msweli, he has also done a work that speaks to being muzzled, titled Forced Silence. It was exhibited at the Yebo! Art Gallery in Ezulwini in 2017 under the banner of “eSwatini Now”.

“People of this country used to call it a peaceful country,” says Mkhabela. “I believe it wasn’t peaceful. It was quietness, forced silence. We have something to say but we can’t speak because we are forced not to say anything … about the political situation of the country.”

Mkhabela’s artworks also hit hard at King Mswati III’s security forces. One of them features a map of the country pierced by a bullet. It is inspired by the teachers shot on 30 October while en route to the capital of Mbabane to demand a salary review. “There are people who still support the current system,” says Mkhabela. “I wanted to show that the nation is divided.”

He has another piece titled Patriotic that depicts a man being strangled by a rope bearing the colours of eSwatini’s flag. “There are patriotic people [who] are hanging on a patriotic rope while they are muzzled. There are a lot of people in rural areas who have no income, they are poor, but you can’t tell them anything about the regime. You can be killed if you say something bad about the regime,” Mkhabela says.

“The shield behind the person’s head is supposed to be protection, but you can see it has bullet holes, which means the protection is not practical anymore as the government is shooting its own citizens.”

Oppressed on many levels

Another drawing, titled Blood, Sweat and Tears, depicts a woman with a headwrap who has blood on her face. This is in reference to impoverished emaSwati who have been subjected to economic terrorism by the regime and forced to accept exploitative jobs, yet they are the main producers of the country’s wealth – which Mswati claims for himself and his cronies.

“I was thinking of the women who work in factories, especially in Matsapha … you will be surprised there are people who earn very little,” says Mkhabela, who has worked in factory conditions that he compares to “enslavement”.

Although Mkhabela, Msweli and others make art critical of the regime, they say they have not yet experienced any brutality from it. This is mainly because, says Mkhabela, “artists are not taken very seriously in the country. [The government thinks] it is people playing with pencils. That is how they take art anyway, unless you draw the queen or the king or the prime minister.”

Despite the underwhelming support these artists get, they aren’t about to stop documenting the uncomfortable realities, or showing the viciousness with which the regime treats its own people. This is revolutionary work propelled by being alive and sensitive to injustices, they say.

“For a nation not to appreciate or allow for critical theory or critical conversations to happen around history and how things became what they are now is short-sighted,” says Msweli. “It is through history where we start piecing things together, seeing the mistakes which were made, seeing also the paths that were taken and to better or improve what was laid out before.”