Protest and policing

Riots are communities defining what counts as police brutality and to set the limits of authority. It is here, not in the courts, that our rights are established.

Author:

4 June 2020

This is an excerpt from Our Enemies in Blue: Police and Power in America (AK Press, 2004/2015), first published by Roar Magazine.

We’ve been here before.

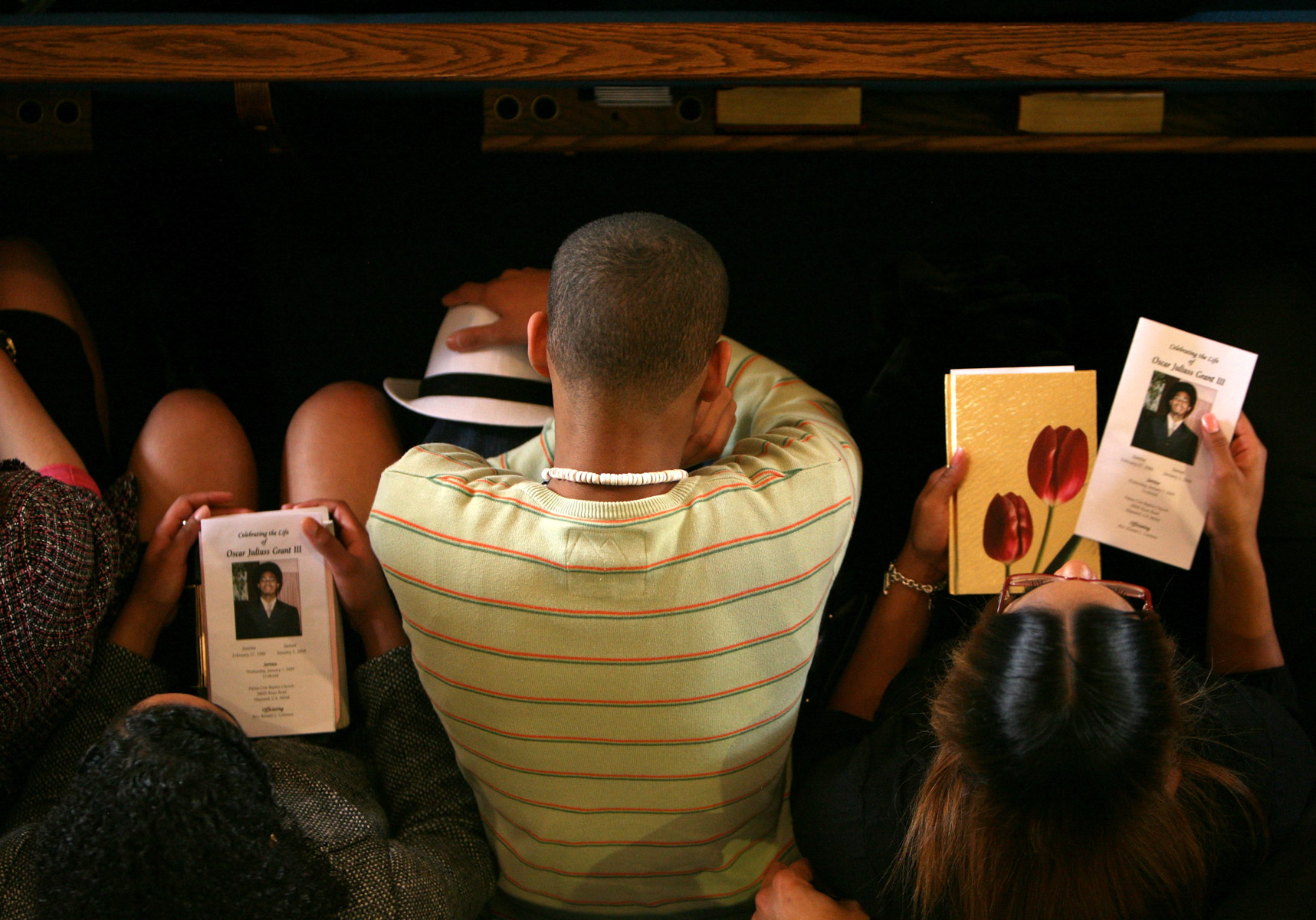

In the first hours of 2009, police boarded a Bay Area Rapid Transit train, responding to a call about a fight. They detained several young men, most of them black, among them one named Oscar Grant. As Grant was lying facedown on the platform being handcuffed, one officer, Johannes Mehserle, drew his gun, shot him in the back, and killed him.

The entire incident was recorded on video from multiple angles. Several witnesses were filming with their cell phone cameras when Grant was shot; afterward, they hid the cameras from police, and then posted the footage on the internet. Within days, demonstrations were organised in Oakland, and quickly escalated into riots – beginning with an attack on a police car parked in front of the BART headquarters. More than 300 businesses and hundreds of cars were damaged in the unrest. Police responded with tear gas, rubber bullets, an armored personnel carrier and more than a hundred arrests, but demonstrations continued for weeks. A year later, Mehserle was tried and convicted, but of manslaughter rather than murder. Rioting resumed. Damages were estimated at $750 000.

Related article:

While clearly a limited victory, the Mehserle verdict remains remarkable. Looking back over the 15 previous years, the San Francisco Chronicle could find only six cases in which police were charged for on-duty shootings, and none of the 13 officers involved were convicted. “If there’s one lesson to take from this,” a participant in the unrest was later to conclude, “it’s that the only reason Mehserle was arrested is because people tore up the city. It was the riot – and the threat of future riots.”

The basics

We are encouraged to think of acts of police violence more or less in isolation, to consider them as unique, unrelated occurrences. We ask ourselves always, “What went wrong?” and for answers we look to the seconds, minutes or hours before the incident. Perhaps this leads us to fault the individual officer, perhaps it leads us to excuse him. Such thinking, derived as it is from legal reasoning, does not take us far beyond the case in question. And thus, such inquiries are rarely very illuminating.

The shooting of Oscar Grant, the beating of Rodney King, the arrest of Marquette Frye, the killing of Arthur McDuffie – any of these may be explained in terms of the actions and attitudes of the particular officers at the scene, the events preceding the violence (including the actions of the victims), and the circumstances in which the officers found themselves. Indeed, juries and police administrators have frequently found it possible to excuse police violence with such explanations.

The unrest that followed these incidents, however, cannot be explained in such narrow terms. To understand the rioting, one must consider a whole range of related issues, including the conditions of life in the black community, the role of the police in relation to that community, and the history and pattern of similar abuses.

If we are to understand the phenomenon of police brutality, we must get beyond particular cases. We can better understand the actions of individual police officers if we understand the institution of which they are a part. That institution, in turn, can best be examined if we have an understanding of its origins, its social function, and its relation to larger systems like capitalism and white supremacy.

Let’s begin with the basics: violence is an inherent part of policing. The police represent the most direct means by which the state imposes its will on the citizenry. When persuasion, indoctrination, moral pressure and incentive measures all fail – there are the police. In the field of social control, police are specialists in violence. They are armed, trained and authorised to use force. With varying degrees of subtlety, this colours their every action. Like the possibility of arrest, the threat of violence is implicit in every police encounter. Violence, as well as the law, is what they represent.

Institutionalised brutality

Despite the official insistence to the contrary, it is clear that police organisations, as well as individual officers, hold a large share of the responsibility for the prevalence of police brutality. Police agencies are organisationally complex, and brutality may be promoted or accommodated within any (or all) of its various dimensions. Both formal and informal aspects of an organisation can help create a climate in which unnecessary violence is tolerated, or even encouraged.

Among the formal aspects contributing to violence are the organisation’s official policies, its identified priorities, the training it offers its personnel, its allocation of resources and its system of promotions, awards and other incentives. When these aspects of an organisation encourage violence – whether or not they do so intentionally, or even consciously – we can speak of brutality being promoted “from above”. This understanding has been well applied to the regimes of certain openly thuggish leaders – Bull Connor, Richard Daley, Frank Rizzo, Daryl Gates, Rudolph Giuliani, Joe Arpaio (to name just a few) – but it need not be so overt to have the same effect.

On the other hand, when police culture and occupational norms support the use of unnecessary violence, we can describe brutality as being supported “from below”. Such informal conditions are a bit harder to pin down, but they certainly have their consequences. We may count among their elements insularity, indifference to the problem of brutality, generalised suspicion and the intense demand for personal respect. One of the first sociologists to study the problem of police violence, William Westley, described these as “basic occupational values”, more important than any other determinant of police behaviour.

Police violence is very frequently over-determined – promoted from above and supported from below. But where it is not actually encouraged, sometimes even where individuals (officers or administrators) disapprove of it, excessive and illegal force are nevertheless nearly always condoned. Among police administrators there is the persistent and well-documented refusal to discipline violent officers; and among the cops themselves, there is the “code of silence”.

Police brutality does not just happen; it is allowed to happen. It is tolerated by the police themselves, those on the street and those in command. It is tolerated by prosecutors, who seldom bring charges against violent cops, and by juries, who rarely convict. It is tolerated by the civil authorities, the mayors and the city councils, who do not use their influence to challenge police abuses. But why?

The answer is simple: police brutality is tolerated because it is what people with power want.

Related article:

This surely sounds conspiratorial, as though orders issued from a smoke-filled room are circulated at roll call to the various patrol officers and result in a certain number of arrests and a certain number of gratuitous beatings on a given evening. But this is not what I mean. Rather than a conspiracy, it is merely the normal functioning of the institution; it is just that the apparent conflict between the law and police practices may not be so important as we tend to assume. The two may, at times, be at odds, but this is of little concern so long as the interests they serve are essentially the same. The police may violate the law, as long as they do so in the pursuit of ends that people with power generally endorse, and from which such people profit.

When the police enforce the law, they do so unevenly, in ways that give disproportionate attention to the activities of poor people, people of colour, and others near the bottom of the social pyramid. And when the police violate the law, these same people are their most frequent victims. This is a coincidence too large to overlook. If we put aside, for the moment, all questions of legality, it must become quite clear that the object of police attention, and the target of police violence, is overwhelmingly that portion of the population that lacks real power. And this is precisely the point: police activities, legal or illegal, violent or nonviolent, tend to keep the people who currently stand at the bottom of the social hierarchy in their “place”, where they “belong” – at the bottom.

Put differently, we might say that the police act to defend the interests and standing of those with power – those at the top. So long as they serve in this role, they are likely to be given a free hand in pursuing these ends and a great deal of leeway in pursuing other ends that they identify for themselves. The laws may say otherwise, but laws can be ignored.

Related article:

In theory, police authority is restricted by state and federal law, as well as by the policies of individual departments. In reality, the police often exceed the bounds of their lawful authority and rarely pay any price for doing so. The rules are only as good as their enforcement, and they are seldom enforced. The real limits to police power are established not by statutes and regulations – since no rule is self-enforcing – but by their leadership and, indirectly, by the balance of power in society.

So long as the police defend the status quo, so long as their actions promote the stability of the existing system, their misbehaviour is likely to be overlooked. It is when their excesses threaten this stability that they begin to face meaningful restraints. Laws and policies can be ignored and still provide a cover of plausible deniability for those in authority. But when misconduct reaches such a level as to provoke unrest, the battles that ensue do not only concern particular injustices, but also represent deep disputes about the rights of the public and the limits of state power.

On the one side, the police and the government try desperately to maintain control, to preserve their authority. And on the other, oppressed people struggle to assert their humanity. Such riots represent, among other things, the attempt of the community to define for itself what will count as police brutality and where the limit of authority falls. It is in these conflicts, not in the courts, that our rights are established.