Prisons are for profit, not our safety

In Abolition Geography, contemporary thinker Ruth Wilson Gilmore looks at crime, incarceration and alternatives that focus on social upliftment rather than the prison-industrial complex.

Author:

Photographer:

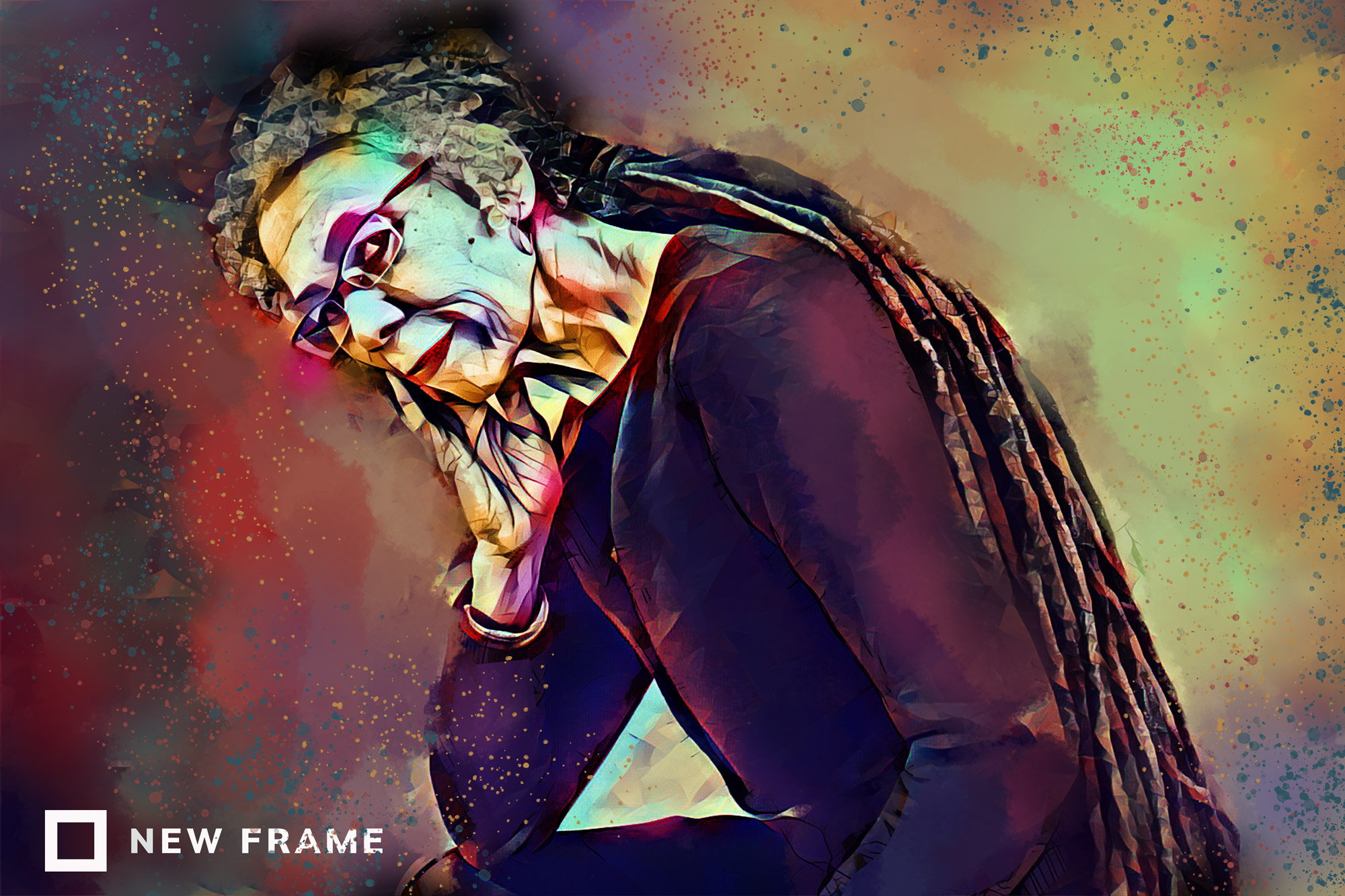

Illustrator: Anastasya Eliseeva

1 July 2022

American scholar and activist Ruth Wilson Gilmore is one of the most important contemporary thinkers on the key political issues of crime, police power and justice. In her 2007 book Golden Gulag, she demonstrated how the capitalist state responds to problems of rising inequality and unemployment by incarcerating and criminalising impoverished people.

Instead of making society safer by isolating dangerous people from it, her research shows that the “prison-industrial complex” of militarised police and jail contractors is dedicated only to its own perpetuation – and massive profit. Her work has focused primarily on the United States, but as she says in an interview with the Antipode journal, American tactics of social control have a global reach and influence.

Alongside activists like Angela Y Davis, Gilmore was one of the founders in 1998 of Critical Resistance. This abolitionist group holds that not only is the current system of police and prisons repressive, but it is also wasteful of public resources and fundamentally incapable of creating public safety. Critical Resistance has been involved in campaigns such as organising against the construction of new prisons and calling instead for political and economic interventions to address the root and branch causes of insecurity.

Related article:

In the aftermath of the Black Lives Matter movement and the explosive George Floyd protesters of 2020, abolition has gone from being perceived as a marginal, radical idea to receiving major media attention.

Gilmore’s writing and public discussions have made her something of a pop culture icon, with Jay-Z citing her work in a Time interview. Other fans started the charming Ruth Wilson Gilmore Girls Twitter account, which combines her quotes with screenshots from the 2000s television series – a surprising but effective way to raise public consciousness about abolition and alternatives.

Tectonic forces

Her new book, Abolition Geography: Essays Towards Liberation (Verso 2022), collects writing and discussions from the 1990s to the present. Introduced by a stimulating essay by Brenna Bhandar and Alberto Toscano, it ranges from theoretical chapters originally published in academic journals to public speeches and interviews conducted with other scholars. This anthology format allows the reader to see how Gilmore introduces, experiments with and then develops ideas in real time, taking us from the 1992 Los Angeles riots to the 2021 neo-fascist attack on the US Capitol building.

The book uses political and social geography to explore how the spaces of daily life are constructed by power and money. For Gilmore, the material force of the police officer’s nightstick or the ominous thud of the slamming jail door have a deep history. They are the contemporary expressions of an economic system that goes back to the horrors of the Atlantic slave trade and thrives on racial, class and gender domination. Underpinning this is a social control ideology that sees the impoverished as synonymous with crime and chaos – people who need to be kept in line by the security state.

Related article:

Abolition Geography allows us to see how her personal life has intersected with great political and social clashes. Born in 1950 in New Haven, Connecticut, she explores how the city’s main employer, the Winchester rifle company, both provided jobs for skilled Black labourers such as her father in a highly segregated era while also manufacturing arms that were used in wars of colonial and commercial expansion. Rather than simplifying these contradictions, she highlights them as a way of showing how all our lives are shaped by tectonic forces of history.

Gilmore’s youth and education coincided with the mass movements of the late 1960s and early 1970s. In the US, she says, Black liberation struggles, the anti-war counterculture and the feminist and ecological challenges to patriachal domination of people and the planet collectively suggested that a very different form of democracy was being born. This sparked furious repression by the US police and security agencies. As part of their Cointelpro counter subversive operations, the FBI planted informants and inflamed tensions between radical groups. In 1969, Gilmore’s cousin John Huggins, a Black Panther Party leader in Los Angeles, was shot and killed by members of the US Organization, a direct product of this counter-subversive strategy.

Radicals, punks and miscreants

The backlash against the long 1960s was ultimately resolved in the form of both neoliberal economics (which included the rollback of social safety nets and collective organisations, and an increased official hostility to working people and the impoverished) and neoconservative ideology. Ronald Reagan and other leaders offered a solution that painted “decent” people as under threat from radicals, street “punks” and other miscreants.

The solution was an indefinite expansion of prisons and militarised police (such as the Los Angeles Police Department inventing the concept of special weapons and tactics units, or SWAT teams, for urban counterinsurgency in the wake of the 1965 Watts uprising ) to keep this imagined criminal underclass behind bars.

But as she conducts extensive research over the 1990s and 2000s, endlessly travelling the California highway system, she uncovers a very different picture. Instead of being driven by public safety, prisons are used for collective “social warehousing”. As deindustrialisation and rampant inequality intensify while state support and social solidarity decline, more people are pushed into the margins and work in illicit economies such as the drugs trade.

Related article:

While the US prison system occasionally nets a bona fide villain, like a Jeffrey Epstein or a Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzman, far more inmates are people who fell on hard times and got into trouble with the authorities, often for non-violent and drug-related crimes and misdemeanours.

They are put into penal institutions that are effectively universities of crime, ruled by the sadism of guards and gang violence. In stark contrast to taking problems of violence and dysfunction “off the streets”, the authorities deepen them. They lock inmates, their families and communities into multigenerational cycles of conflict with the state while simultaneously preventing them from bettering their situations.

And when it comes to problems such as interpersonal violence and domestic abuse, the current system fails to provide material and social support to victims while neglecting more effective violence-reduction strategies.

Liberation work

Mass incarceration is, however, very good for the bottom line of the prison-industrial complex. Prisons are expensive to build and maintain and receive lucrative government contracts. This is why parts of the construction, service and security industries have a vested interest in having as many people behind bars as possible.

Gilmore discusses how this concept was inspired by president Dwight D Einsenhower’s farewell address in 1961, in which he warned that the Cold War had helped create a “military-industrial complex” of defence contractors and political interests with a vested interest in permanent warfare. Even an arch-capitalist like Einsenhower saw the dangers of this system, warning in an earlier speech that “every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired signifies, in the final sense, a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and are not clothed”.

Related article:

She extends this to today’s prison-industrial complex and the proliferation of expensive “wars” on crime and drugs that are by their nature intended to never end. Not only is this highly cynical, but it also precludes more innovative solutions to insecurity. Problems rooted in poverty, addiction and social decay are denied the deeper social interventions they need in place of a crude and often actively sadistic regime of police and prisons.

The alternative, says Gilmore, is the work of liberation. As her years of activism and scholarship have shown her, the police and prisons of today are not decent institutions that have been corrupted. They were set up to work exactly like this from their inception.

At the same time, things such as crime and violence are real social problems that need to be robustly addressed. But the state and the security industries legitimise their expansion through this visceral appeal. After all, no one wants to be a victim of theft or attack. But the “solutions” they pander work not to solve problems but to perpetuate them.

Social support over prisons

As Gilmore says convincingly, this means concepts of abolition and community self-defence (as discussed in Geo Maher’s book A World Without Police) are not utopian slogans but pragmatic and realistic. In the face of a spiralling social, economic and ecological catastrophe, it’s clear that the police and prisons are not going to protect us from an era of crisis.

Related article:

Discussing her activist past in a humane and relatable way, Gilmore says abolition means the actual, immediate work of creating public safety from below. From her perspective, continuing housing struggles are a form of abolition work in that they are fighting to make life more stable and peaceful for the communities involved.

But it also means the longer-term project is building alternative social systems – ones that favour social support, conflict resolution and the creation of more stable societies – and not more cages.