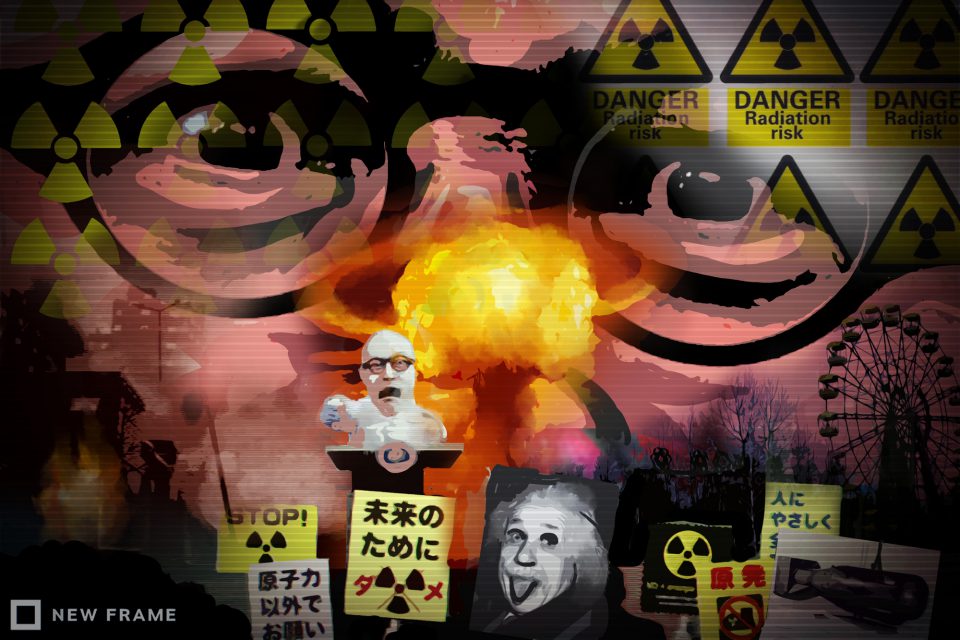

Political Songs | You Can’t See It – Rankin Taxi

‘Missile envy’ ensures that nuclear power remains the ultimate symbol of masculinity despite its danger to humanity, as Rankin Taxi encapsulates in the song he was forced to update after Fukushima.…

Author:

23 August 2019

“My warhead is bigger than yours!”

There’s nothing that shouts global masculinity louder than “missile envy”. The term is the title of an influential 1984 book by Australian anti-nuclear peace activist Helen Caldicott, dating back to the Cold War when, according to her feminist critique, nuclear proliferation was driven by male ego with very Freudian undercurrents. And like a lot of male boasting about sexual prowess, it’s not subtle.

In the 1980s, American academic Carol Cohn spent a year working among civilian nuclear strategists, war planners, weapons scientists and arms controllers. “What struck me was how removed they were from the human realities behind the weapons they discussed,” she wrote recently in The New York Times.

“This distancing occurred in part through a professional discourse characterised by stunningly abstract and euphemistic language – and in part through a set of lively sexual metaphors.

“The human bodies evoked were not those of the victims; instead, there were conversations about vertical erector launchers, thrust-to-weight ratios, soft lay downs, deep penetration and the comparative advantages of protracted versus spasm attacks — or what one military adviser to the National Security Council called ‘releasing 70 to 80 percent of our megatonnage in one orgasmic whump’.”

Related article:

It hasn’t changed post-Cold War. Just look at the current proponents who have it – Russia, India, Pakistan, the United States, Israel, North Korea and their aggro, macho leaders – to see that nuclear power remains the ultimate symbol of masculinity. In 1998, Indian politician and Hindu chauvinist Bal Thackeray justified his country’s explosion of five nuclear devices with “we had to prove we are not eunuchs”.

Anti-nuclear opposition gets belittled by linking it to “womanhood” or “femininity”. As gender activist Ray Acheson told the Nuclear Age Peace Foundation: “There is the denial of people’s – especially women’s – lived experiences of the weapons, that is, denial of others’ perceptions of reality. Such denial is characteristic of patriarchy and psychologically abusive relationships.”

Politics in a picture

There’s a mundane, official picture that the Kremlin released at 4pm on Thursday 28 August 2014 that illustrates the relationship between those who have nuclear, and those that want it, extremely well.

Titled “Vladimir Putin held talks with President of the South African Republic Jacob Zuma, who is in Russia on a working visit”, the picture of the two men was taken in Moscow earlier that day, seated in a colossal, opulently furnished room in the Russian president’s residence.

The bland accompanying statement made no mention that it was the fourth time they had met in just 15 months, excluding apparently regular telephone conversations. Also, no word that they were scheduled to have two more private, in-person talks before the end of 2014 or of the additional meetings that were to follow the next year, some related to the Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (Brics) economic bloc.

Zuma’s low-key, six-day visit to Russia came after a strenuous election campaign, and just months after the release of the public protector’s report that found the president and his family had unduly benefitted from upgrades to his Nkandla homestead to the value of R246 million.

Back to the picture of the two powerful presidents… At home, Zuma normally oozed masculinity, coming across as more macho than a double cab, 4×4 bakkie with truck nuts parked illegally on a pavement outside Tshwane’s Loftus Versfeld rugby stadium on match day. But not that day next to Putin. A tired-looking Zuma’s posture makes him look weak, his knees look knobbly in his dark blue suit, his feet close to each other, his toes pointing awkwardly inwards.

Dressed in a good dark charcoal suit, the decade younger Putin’s legs are wide apart, his feet in quality black leather shoes firmly planted a metre apart on the gold-patterned carpet. It makes him look like a virile, confident and powerful Mafia don on home turf.

Related article:

But it’s no surprise, as political scientist and author of the book Sex, Politics, and Putin: Political Legitimacy in Russia Valerie Sperling wrote in a blog post for Oxford University Press: “A key element of Vladimir Putin’s legitimation strategy has been the cultivation of a macho image. His various public relations stunts subduing wild animals, playing rough sports, and displaying his muscular torso, drew on widely familiar ideas about masculinity.”

During Zuma’s meetings with Putin, nuclear must have featured prominently. Last year, former finance minister Nhlanhla Nene told the Zondo inquiry into state capture that he believed Zuma fired him in 2015 because he refused to endorse a nuclear deal with Russia. It would have cost R1.45 trillion, the equivalent of 90% of South Africa’s budget, reported Business Day.

If fulfilled, Zuma’s missile envy would have put the country into even deeper trouble. Fortunately, President Cyril Ramaphosa told Putin at a private meeting during last year’s Brics summit in Johannesburg that South Africa couldn’t afford it. We’re lucky because nuclear, it seems, breeds repeat offenders. Or people who can’t learn from others’ mistakes.

Musical response to disaster

In Japan, parents have been a major driving force against nuclear. On 11 March 2011, a massive earthquake hit Japan’s coast, the most powerful the country has ever experienced. What became known as 3/11 unleashed a tsunami that killed more than 19 000 people, mainly through drowning.

The destructive power of the tsunami triggered a triple meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant on the country’s northeast coast, making it the most devastating nuclear accident since the Chernobyl disaster on 26 April 1986.

Related article:

Tens of thousands of people had to be evacuated from Fukushima for fear of radiation. A tiny number of them have been able to return to their homes, eight years later.

After 3/11, anti-nuclear protests saw parents and grandparents with placards demanding “Protect our children”. In her book, The Revolution Will Not Be Televised: Protest Music After Fukushima, musicologist Noriko Manabe wrote that several musicians active in the anti-nuclear movement are parents to young children.

Veteran Japanese reggae artist Rankin Taxi’s daughter was seven when Chernobyl happened. This accident was his motivation to write the song You Can’t See It, and You Can’t Smell It Either. Rankin Taxi became concerned about the potential of radiation to cause cancer in children and felt that Japan should put children’s health first.

Do I want to die from radiation? No way!

It’s only a leak, but it can’t be stopped. No way!

Do I want to be hated by children to be born in the future? No way!

Rankin Taxi told Manabe: “I thought an accident as huge and horrible as Chernobyl would never happen in Japan. Nuclear plants here in Japan were supposed to be safe. But at the same time, I thought – well, what if the worst were to happen?”

It’s safe, it’s safe!

It’s safe, because I’ve decided it is!

It’s safe, even if it’s leaking a lot of water!

It’s safer than Chernobyl!

Even if there’s an earthquake, it’s safe…

As long as we control the media, it’s safe…

It’s safe until there’s an accident!

And then came Fukushima. Rankin Taxi reworked the song to reflect the disaster.

In May 2011, Rankin Taxi and the Dub Ainu Band’s new version of You Can’t See It, and You Can’t Smell It Either was released on YouTube. Commercial radio stations didn’t want to play it because of corporate censorship. The lyrics had changed from “What if there were an accident?” to “We have had a serious accident”.

In Manabe’s book, Rankin Taxi says it was a “sad indication” of the continued domination of pro-nuclear forces over the 22 years separating the two nuclear events.