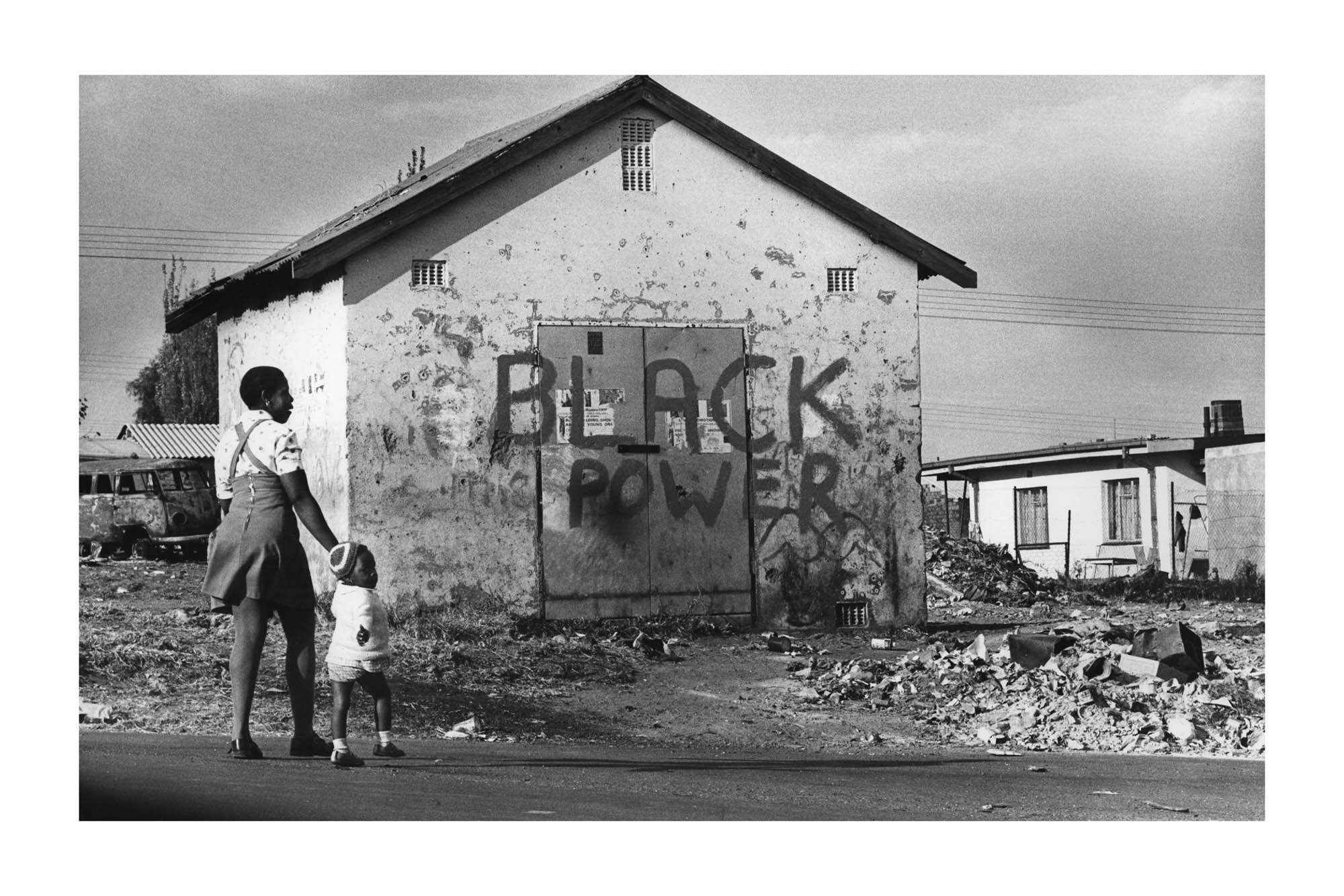

Peter Magubane, a photographer against apartheid

While documenting the country’s most brutal moments and protecting other journalists, Magubane was shot, beaten, tortured and jailed. He is now 87 and is an icon of photography.

Author:

17 June 2019

On 16 June 1976, photographer Peter Magubane went into Soweto at the break of dawn. The protesting children came up the street to meet him, and said, “Stop! We want no pictures.” Magubane replied, “A struggle without documentation is no struggle,” and asked for other photographers, black and white, to have the right to document. The youth listened and allowed him to go ahead.

At that point in his career, the 44-year-old Magubane had been tortured, made to stand on bricks for 120 hours, been put away in solitary confinement for a record 586 days, had his home in Soweto burnt down by police trying to destroy negatives and had just come out of a five-year banning order.

The 1976 uprising became the defining work of his career. His Young Lions coverage made the front page of The New York Times, as he followed the event’s echoes around the country.

Related article:

In Alexandra on 17 June 1976, a policeman used a truncheon to break Magubane’s nose while destroying the spool of his film. He was more furious about the loss of work than his nose. “You damn, bloody fool,” he said to the policeman, “you have just lost our history.” He picked up his camera and went straight back into the action, taking remarkable images, such as the now iconic shot of two youths confronting live ammunition holding only a dustbin lid and handfuls of stones.

On 30 May 2019, photographer Ruth Motau along with the Market Photo Workshop honoured Magubane and revolutionary photographer Dr Santu Mofokeng as part of a long-term initiative to give roses to the legends while they live. Mofokeng’s famous work Chasing Shadows looked at the role religion played in sustaining apartheid but poor health meant he was not at the event.

From driver to photographer

Magubane has a firm, assertive, proactive and innovative approach to photography. He grew up in Sophiatown as an only child. His father, a donkey-cart fruit vendor, gave him his first camera, a Kodak Brownie. He started taking portraits at school and when he saw the images of Robert Capa at the Family of Man exhibition at the Rand Show, he decided to become a photojournalist.

Magubane joined Drum magazine as a driver. As part of this golden constellation of writers and journalists, he learnt on the job. Whilst editor Tom Hopkinson encouraged him to get closer to the action during the Sharpeville massacre, Bob Gosani was his direct mentor and showed him the ropes.

Magubane was always a fast thinker. He outwitted the agents of the apartheid government on many occasions by disguising his camera in either a loaf of bread, a pint of milk or even a Bible. Once, when the cops asked him why his passbook was not signed, he asked for a pen and signed it himself. They let him go.

Related article:

In The World of Nat Nakasa, close friend and colleague Nakasa writes about how the two were investigating child labour on the Bethal potato farms when the police arrived. Faced with possible violence, Magubane flipped up the aerial on his light meter and explained it was a live radio transmitter linking the scene to his editor. The journalists got away.

In the late 1970s, Magubane temporarily moved to New York where he worked for Time magazine. The late John Morris, photo editor of Life Magazine introduced him to Cornell Capa, Robert Capa’s brother. Capa helped publish his first book, Magubane’s South Africa (1978). This influenced a generation of South African photographers. João Silva, co-author of the Bang Bang Club, describes Magubane’s South Africa together with Davis Douglas Duncan’s This is War as the educational blueprint for his photojournalism career. As a high-school dropout, Silva relied on those books to see how “genius manifests itself especially during those times of danger,” as he said.

Photographing history, saving lives

Magubane’s images documented many pivotal moments in South African history, including the signing of the Freedom Charter, the Rivonia Treason Trial, the 1976 uprisings, the states of emergency and the Sharpeville, Boipatong, Uitenhage and King Williams Town massacres.

These images immortalised the sacrifice of many South Africans, exposed apartheid and paved the way for transformation. In the field, Magubane was shot 17 times with buckshot and rubber bullets. He often protected fellow photographers from crowds and dangerous situations. Photographer Louise Gubb recalls being in Gugulethu in 1985 with Sarah Leen, the photo editor of National Geographic. Faced with a crowd of angry comrades holding petrol bombs, Magubane was out the car and on the bonnet in a flash shouting: “Stop, these are the people who are taking our struggle to the world.” The comrades listened.

Related article:

Musician and journalist Roger Lucey writes in his memoir, Back in from the Anger (2012), how he nearly became the victim of a necklacing in Venda.

He had arrived in Thohoyandou to film a funeral for news. The crowd of agitated youth mistook him for a plain-clothes policeman and isolated him from his soundman Ian Herman. A news cameraman working for an American broadcaster jumped on the bonnet and started filming as they brought a tyre and petrol.

Suddenly through the crowd came Magubane, jumped on a bonnet of a vehicle, ordered the cameraman off and called for silence. He said in Tshivenda. “If you kill him, you might as well kill me too.” The crowd obeyed.

Magubane’s bravery was also heralded in Leandra where he stopped enraged youths from hacking the entire family of mother, grandmother and daughter of an alleged impimpi to death.

As dramatic as the photographs might have been, Magubane’s attitude was always: “I have got my pictures. I can save a life now. That is more important.”

A cultural world after apartheid

Magubane was never affiliated with any political party. He was there to document.

From 1990-1994 he was Nelson Mandela’s official photographer, photographing his return home to Orlando West and the subsequent world tour. He also helped put together Mandela’s autobiography Long Walk to Freedom (1994) and is thanked in the book.

After democracy, Magubane quit photojournalism and turned to documenting South Africa’s cultures. This was to complete his catalogue, showing him as both a struggle photographer and storyteller. The book Vanishing Cultures of South Africa introduced a new generation to his work.

His granddaughter, performance artist Lungile Magubane, took this book to a grade four show-and-tell. She realised for the first time what her oupa did. “My grandfather changed my perception of what it is like to be black,” she explained. “His bravery in being the way he wanted to be, and needed to be, is emblazoned in the way we live today.”

In 2000, Magubane was joined by a student of liberation history, David Meyer-Gollan. Sensing the importance of documenting the documenter, Meyer-Gollan dropped his career as a film-maker and dedicated his career to Magubane, fulfilling the role of manager, lawyer, archivist, curator and editor.

“Magubane is at one with his subject,” Meyer-Gollan enthused of his mentor and friend. “Nothing is posed or set up. He is real, allowing the subjects to tell their own stories through the images.”

At 87, Magubane is still strong. He advises young aspiring photographers to just create work, noting that he never waited for editors to assign him jobs. It is this attitude that has driven Magubane to publish 23 books so far, with more to come. He is one of the world’s most acknowledged photographers, with nine honorary doctorates to date.

David Goldblatt & Peter Magubane: On Common Ground opens at the George Bizos Gallery of the Apartheid Museum on 29 June.