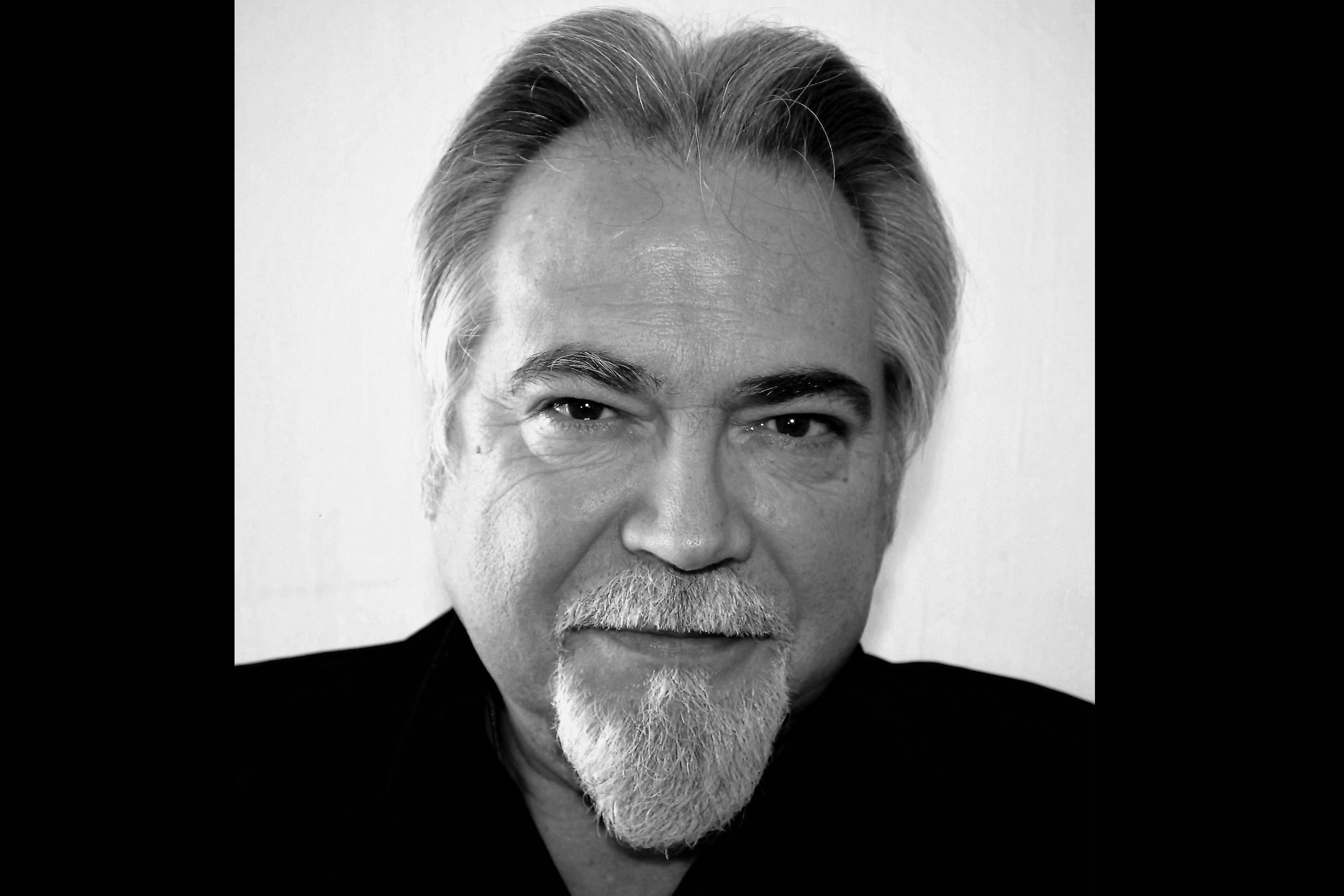

Part two | Patric Tariq Mellet on culture and identity

The Lie of 1652 is a decolonised history of land in South Africa. This is part two of a Q&A with the author, in which he speaks about cultural genocide and identity in the country.

Author:

28 October 2020

In The Lie of 1652: A Decolonised History of Land, writer, heritage activist and former liberation movement cadre Patric Tariq Mellet provides a critical analysis of how African identities, including those of the Khoe and San people, were de-Africanised, leading to what he refers to as the Khoe and San’s “cultural genocide”.

On his site, Camissa People: Cape Slavery and Indigene Heritage, he writes: “My family were poor working people from what was regarded as a grey area community of people who were classified during the apartheid years as ‘coloured’, ‘Indian’ and ‘white’ in the same family. Both my grandmothers were classified ‘coloured’ and my paternal grandfather an Afrikaner with strong Camissa lineage and my maternal grandfather was an Englishman. My family contradicted the official segregationist paradigm as we did not neatly fit into these labels.”

Related article:

In the second part of Yvone Phillis’ interview with Mellet about his book, he speaks about how identities were reconfigured and socially engineered to justify the dehumanisation, exploitation and violence of colonialism and apartheid. He calls for a consideration of land that first considers people holistically, one that is not part of what he calls “an elite bubble” defined by capitalism.

Yvonne Phyllis: You say there was a cultural genocide of the San and Khoe people. Why was this ‘cultural genocide’ important for the colonial and imperial system?

Patric Tariq Mellet: The starting point of this is a particular doctrine that arose from the papacy. The papacy had a doctrine called Terra Nullius, the empty land doctrine. Basically what the papacy said is that Europeans, in going out and exploring the world, wherever there were non-Christians, there were no people, it was an empty land.

So when the Europeans came around South Africa, they encountered various peoples at different times and in different places. The Europeans thought of Khoe and San people as what the Enlightenment period called “noble savages”. The “noble savage” was considered to be half human and half beast, that it was a “pre-human” race. So the Europeans’ argument was that South Africa was actually free of people, only these groups, half animal, half humans, who are now being threatened by an invasion of a foreign alien black people. And that the Europeans, in fact, were doing a favour to these half people, the Khoe and San, by protecting them from these black alien invaders. So, a peculiar, twisted way of looking at the whole history and heritage. As I said to you before, South Africa had many different ethnicities living across the country by the time the Europeans turned up here, but this was the thought process, about how they dealt with indigenous people.

The argument, too, was that these first indigenous peoples that they met had no concept of land ownership, no concept that the land, whether communal or individual, belonged to them. Again, you know, if you read Van Riebeeck’s diary, it shows very clearly the Khoe people articulating land ownership, that they knew exactly that this was their land that was being invaded.

Before the Europeans came here, we had an agricultural economy in some areas, the growing of crops, millets etc, we had animal husbandry, pastoralism, and we had hunting and gathering. What the Europeans always tried to do was to ethnicise these different modes. The reality is that in all of these groups, all of these modes existed, and not just one mode or another.

So, you began to have the stereotyping of people, which has been overlaid on our whole approach to history. The nature of the three or four groupings of people that the Europeans first came in contact with – the San, the Khoe, the Gqunukhwebe and the Xhosa – was such that all had a thriving socioeconomic infrastructure, and with that infrastructure there were different cultural modes. Some were in the early stages of kingdom development, others had a much more flat type of political infrastructure of elders and counsellors, in fact, quite democratic.

If we look at it, there were guides and counsellors and spiritual leaders within the communities, people had a very good idea of rotating cattle seasonally, so that there was time for grasses to rejuvenate and so on. They had been attuned to the value of water, all of these things were there. The European says there was no civilisation, there were just these part-beast creatures around. The distortion of our history starts from that place. So, one has to understand what that early society really looked like, how it was assaulted. The cultural genocide, which I call ethnocide, is the destruction of the ethno-cultural ancestral heritage formations, particularly among the San and the Khoe.

Phyllis: You say some of the racial categories that we use today, such as ‘coloured’, were socially engineered by colonialists, that they are about de-Africanising African identities and are not a true reflection of African identities. Could you expand on this?

Mellet: I wrote my first book about a decade ago, called Lenses on Cape Identities, in which I demolish the notion that identity was something singular and elaborated on the fact that as human beings, from the day we are born to the day we die, we collect and we discard identities. There are many different facets to those identities. There’s a gender facet, there’s a working-class facet to it, there’s a faith facet, there’s many things. What happens in nationalist societies is that people tend to think of identity as race, ethnicity, colour. I broke through that mythology with that book.

The 195 roots of origin of people who are labelled ‘coloured’ today… a very insulting label, a label that implies bastardisation and so on. For me, I saw in my community how lost people are. You know, people going on all sorts of tangents around identity politics. They’re missing the beauty, they’re missing the core identity.

Related article:

It wasn’t just people classified as coloured that were de-Africanised, all Africans in South Africa were de-Africanised in the sense that there were probably up to 200 social identities, social ancestral cultural identities in South Africa. So they took about 70 or 80 of these, and they forced these into 10 rigid linguistic nations. That was de-Africanisation in its true sense. They took more than 50 African identities among those who they called ‘coloured’ and completely obliterated it, and assimilated just about everybody that was not white, but they could not fit into the 10 silos and they called this ‘coloured’.

And it was a deliberate social engineering process that they used to do that. I keep telling people, apartheid did not start in 1948, the entire colonial system up until 1910 and then post-1910 was the manipulation of this thing called race. Through manipulating this, they were able to divide, divide and conquer, divide and rule. That is the logic behind what they were doing and what they still do.

Phyllis: You say that ‘recognising the class criteria of poverty is the main guarantor for the empowerment of the black poor’. I want to relate this to the land question. In terms of access to land in South Africa, whether we talk about urban land or rural land, is there an element of elite capture?

Mellet: If we look at just the figures, 92% of South Africans are people of colour, 8% of South Africans are people of European descent, white. The land, if we go back to 1985, there were over 180 000 white farmers mainly. Today, there are 25 000 white farmers, mainly. A small element of black farming. What we’ve seen is an attrition rate based on a range of factors, the development of superfarms at the expense of smaller farms, but also white farmers’ kids didn’t want to be farmers. They got an education and they went off.

South Africa, in terms of its growth and all of that, requires 200 000 more farmers – and they can only come from the black population – in terms of food security and agribusiness. Those factors, which are pretty much common sense factors, are not thought about. The second thing is that most of these white farmers did not get a standard of living simply from the farm. They utilise their farms as collateral with the banks, to be able to live luxurious lives. So the banks own most of this farmland, but we’re not talking about that subject at all.

Related article:

To address your question, these two observations tell me that the whole land question is in an elite bubble. It’s in the bubble of those who could afford to or were accepted by the banks to basically underwrite their lifestyles, through surrendering their bond, or taking out a bond or mortgaging their property for money at the bank. The other farming method is these huge cooperatives, almost like a super corporate body that runs the farms, these are the farms that do a lot of the export and so on. The concept of small artisanal or craft farmer doesn’t really exist in South Africa. There’s a pocket here and there or an individual here and there in their family that has this type of farming. So our agrarian scenario in South Africa is elite already. What you now have is emerging new elites, who want a cut of that same system. That isn’t restorative justice, that is simply the elite sharing the pie with wannabe elites.

Phyllis: What change would you like to see to ensure that land is not in an elite bubble, as you say?

Mellet: There should be a plan about how we change the farming landscape, in all its many facets. That is the decolonisation path that we need to be taking. So that instead of people being all in an overcrowded slave town, those people will actually have farmsteads. I see this in Thailand all the time. Before 1948, they were in the same position. They didn’t have land. They didn’t have farms. Thailand’s got, you know, 13 million, 14 million small artisanal craft farmers, in other words farmers who do the work themselves on smallish, manageable farms.

I want to see real agrarian reform transformation in South Africa. At this very particular point in time, I see nothing stopping us from doing that. And this isn’t a wholesale takeover of the 25 000 farmers’ farms. It is a scenario where you’re saying we would like a part of your farmland that assists the development around each town with the development of craft farming.

I don’t see the struggle around the land as struggle around real estate. It’s not about transferring real estate from one elite to another. Land is much more than earth. It’s about livelihoods. It’s about social cohesion, identity, all of these things. Our people are in hopelessness at the moment. We need to bring hope. Where is the big plan? There’s no big plan. We also create silly phrases, the phrase that is being used is ‘expropriation of land without compensation’. By using this silly phrase you make a victim out of those who actually expropriated. The real issue is restoration of the land that was expropriated without compensation.

There is also the need of land in the urban environment. The urban built environments are as much a slave town. What we have is people crowded into dormitory areas with no infrastructure, the built environments are miserable. The schools are miserable. There are no community centres. There are no recreational facilities. And people are living on top of each other as back-yard dwellers or they are living in shantytowns on the outskirts without all the basic amenities.

I mean, in my area of Cape Town, every year floods flood up people, every year the windy season causes shack fires. People are living miserable lives. How can we call it freedom? How can we call it liberation?

So, the things that drove me as a young person, to become a freedom fighter, to join the liberation movement, are still here with me now. So why shouldn’t I be behaving as I did then as a young person? We are not employing ideas. What we have are small coteries of people organised into political parties. What we have is party power, there are pyramid schemes of patronage. We don’t have people power, and the direct translation of the Greek demos kratos is people power, it is democracy. We don’t have democracy, we have party power.

Our problem is not one of lack of know-how, and it’s not lack of money. What we have is a mortgage system in the banking environment, and a realtor system in terms of control of land, who dominate this, to deliberately exclude the poor from decent homes and housing.

Related article:

Again, it’s about lack of restorative memory, because the concept of restoration that we have is weird. It’s very middle class and upper class-oriented thinking, it’s people who’ve bought into the system. And what is the system? It is the capitalist system.

What we need in South Africa is a government that is for the many and not the few, as simple as that. It’s about creating a hegemony in our society of the many, as opposed to the present hegemony of the few. It’s as simple as that. For me, an African socialist communitarian system is what we need, that addresses our needs. And it has to clash with the upper classes, we can’t avoid that. That clash doesn’t have to be violent but it can be disruptive, and we need to keep this up as continuous throughout society. We need to think all of this through. But, I really also need to say that we must start to hone in on where the problem really is.

To my mind, the biggest problem is the banking system that we have, and the private land, real estate industry that we have. We’ve got to clash with that. In the city of Cape Town, the government’s got a lot of land, and these aren’t next to [shack] settlement areas, they represent real integration of the population into the built environment of Cape Town. Why is this land remaining idle and not being used innovatively to create housing development and new built environments? People also need better schools. Covid-19 actually exposed how terrible our schools are, when we were being told regularly by the ANC, ‘Pat us on the back, we have done marvels for education.’ It was disgusting, what we saw.

When we think of land, we must think holistically about people. What are our social needs or medical needs, our recreational needs, etc, in an urban environment? And not just accept people putting up matchbox houses that break and crumble within two, three years, and where the bulk of that money hasn’t gone into the community and has gone into some thug’s pocket.

I am socialist-minded in the way that I look at things. I would like, however, to see us less orientated around the European socialists, communists constructs and begin to think about African socialism. In other words, you know, I like the phrase that the Chinese use, they talk of socialism with Chinese characteristics. I would like to see socialism with African characteristics. And this means that our intellectuals, even organic ones like myself who have come from below, that we start to give a vision and a picture to people of something unique, and we don’t just bash out 19th and 20th-century mantras and dogmas and so on. We need to take cognisance of failures in the left arena in Europe.