Part two | How Koeberg’s history impacts today

Apartheid ideology determined who could live and work around the nuclear power station. It’s something to think about as the government moves to extend the life of the plant.

Author:

23 March 2022

It is well understood that the decision to build a nuclear power station in South Africa was as much about military concerns as it was about energy supply. Koeberg provided the perfect cover for the apartheid state to further its uranium enrichment technologies, to provide fuel for Koeberg and the necessary ingredients for nuclear weapons.

There is also little doubt that the apartheid government felt that the construction of a nuclear power station made a powerful political statement about what could be achieved despite growing international isolation. As a 1966 editorial in the Cape Argus newspaper put it, “there is something about nuclear power stations which makes them infinitely desirable to the South African way of thinking. Perhaps it is prestige.”

read more:

A similar sentiment was expressed in the government’s propaganda publication South African Panorama when reporting on the start-up of Koeberg. “South Africa proved yet again that technologically it is among the world’s top countries … South Africa’s brainpower has proved itself in step with the rest of the world.” The fact that the French designed and initially operated the station mattered little.

What is less well known about Koeberg’s history is how apartheid ideology shaped urban development around the power station, who built the plant and who would work there. The racialised history of the power station’s development is worth considering as we face the prospect of its life being extended.

Population control

The first indication that Koeberg would make an impact on apartheid urban planning came at a meeting of the site investigation committee in May 1970. Attendees expressed concern about Mamre because it was being considered as a “large coloured settlement of the future” and would influence attempts to control population growth around the power station. The development of Mamre featured repeatedly in the committee’s discussions. It gives a powerful insight into the casual way in which people were subjected to forced removals and how such removals influenced urban development.

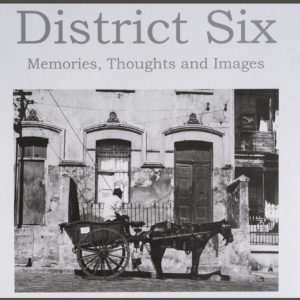

The site investigation committee noted in August 1971 that a new “industrial development area” was proposed to “serve the coloured group area of Mamre”. In a letter from Cape Town’s chief city engineer to the national director of local government, the chief engineer noted that the “Cape magisterial district” had shown a net loss of population of 0.5% per annum over the past decade, “largely due to movement of people out of District 6”. He was unable to say how quickly the Mamre development would grow “as so much will depend on the rate of depopulation and repopulation of District 6”. (The deputy city engineer described the forced removal of District 6 residents as “decentralisation and … resettlement”.)

Related article:

The chief engineer noted that as many as 500 000 “coloured people … may be settled in Mamre” while drawing attention to “the European sector which would be necessary to support the proposed industrial development”. Two years later, the AEB said that if upwards of 500 000 “coloureds” were settled in the area it would have an impact on settlement in other areas around Koeberg. The AEB told the City that any significant development of Mamre “might have political or social implications which you would wish to consider”. It appeared to be warning the City that “white” developments in the area in which the AEB wished to control population growth may have to be sacrificed if the population of Mamre increased as anticipated. Given the dictates of apartheid urban planning, this is an eventuality that had serious political ramifications.

It is not known how the “development” of the Mamre area – subsequently known as Atlantis – was impacted by concerns around its location relative to Koeberg, or how “white” developments within the area of population control around Koeberg were influenced. It may well be that Mamre’s “development” was slowed by the AEB’s concerns, meaning that people who were forcibly removed from Cape Town ended up elsewhere, notably the Cape Flats.

The ‘banality of evil’

The apartheid state was deeply concerned about who would build and work at Koeberg. In 1975, a year before construction began, Eskom made assurances to the Cape divisional council and the Cape provincial administration about labour.

The company said it would build “Bantu quarters” on the site for between 1 000 and 3 000 men, who would be regarded as “temporary inhabitants”. Eskom said it was aware “that the semi-dense bush may create law-and-order problems” and told the Cape governments that it would take the necessary security measures. It assured all parties that no provision had been made for “Bantu operating staff”.

For their part, representatives from the Cape governments called on Eskom to create “recreational and shopping facilities” at the “Bantu quarters” to “prevent an influx of Bantu in Melkbosstrand at weekends”.

Eskom said it was difficult to quantify how much “coloured” labour was needed, but that it would be in sufficient supply because of the Atlantis development, where “coloureds will be able to purchase their own homes at economic and sub-economic levels”. It said semi-skilled “coloureds” could work at the plant, but only if transport to get them to and from Atlantis was provided.

Related article:

These assurances from Eskom were apparently still not enough for one local National Party member of Parliament. He voiced his concerns publicly in 1976 about “black penetration” into traditionally “white” and “coloured” areas by the labourers at Koeberg. The minister for economic affairs at the time assured him that “Blacks” would be properly managed by a white supervisor and would leave the site as soon as it was complete.

As for “whites”, Eskom said it was creating the town of Riebeeckstrand, which was to be completed by 1980. It was designed for 200 homes spread across 850 000m² of land, resulting in large average residential erf sizes of 875m².

How the day-to-day workings of apartheid influenced the construction of Koeberg provides a classic example of how – to use Hannah Arendt’s phrase – the “banality of evil” operates. It shows how mid-level bureaucrats casually implemented the evil of apartheid in the spheres of urban planning and job reservation. One of the most devastating episodes in South Africa’s urban past, the destruction of District 6, is described as “depopulation” or “resettlement”, while all the skilled jobs at Koeberg were reserved for “whites” who were generously accommodated near the power station.

Eskom regularly states how proud it is of Koeberg, seemingly oblivious to its apartheid history. It is time Eskom and the National Nuclear Regulator reflect on its dark history and look to cheaper, more environmentally friendly, decentralised and locally owned sources of renewable energy rather than extend the life of the power station. In doing so, they can consign the ageing plant to history, where it belongs.