Papers from the Left

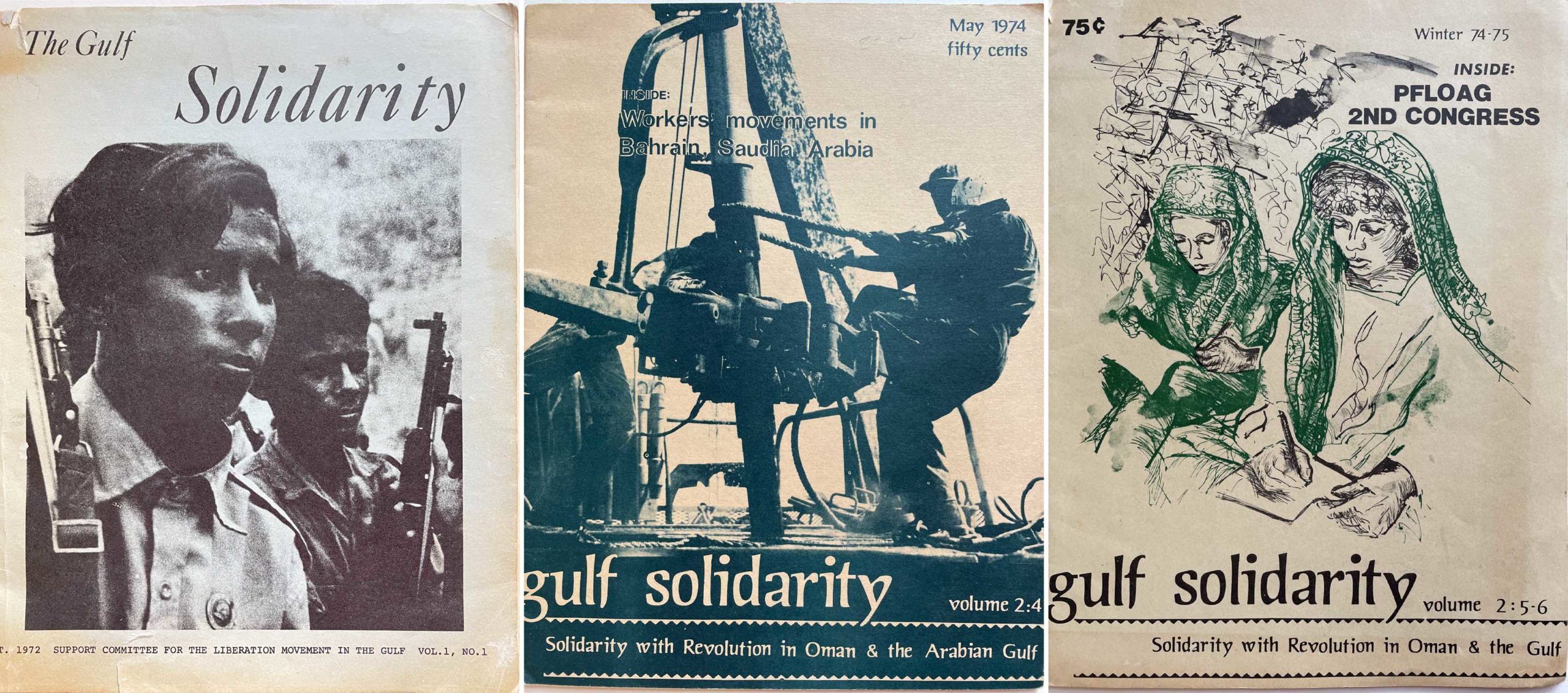

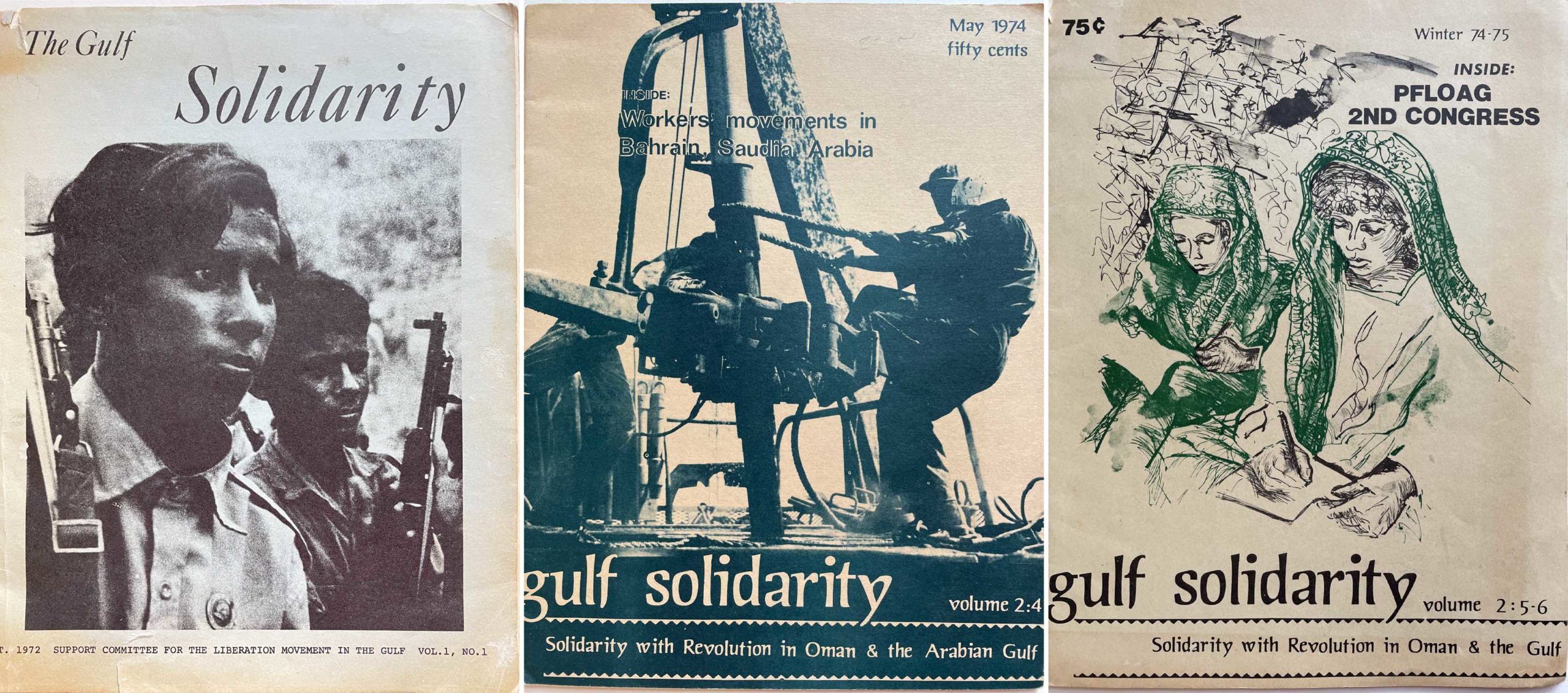

Revolutionary Papers is a forward-thinking archive of anti-colonial zines, newspapers and flyers that taps into popular print culture to offer historical context and present-day relevance.

Author:

1 June 2022

“Post-colonial print culture is kind of trendy these days. There’s all these materials, but what are people doing with them? Other than framing them and putting them up on display as if they’re these freeze-framed, beautiful, aesthetic pieces?” asks historian Koni Benson.

She is one of the co-founders of Revolutionary Papers, a digital archive that focuses on anti-colonial and anti-imperial periodicals. It brings together publications – including cultural and political journals, zines, newspapers and flyers – from revolutionary struggles in the Global South. As co-founder Mahvish Ahmad said at the launch, it’s about celebrating “anticolonial dreams” and those who were “daring to dream on the ground and while running”.

The idea started as a conference, with a public call for such papers. “These were live, living movements trying to do actual things, so what was the movement? How was it produced? From when to when was it produced? Who produced it? Where did it circulate? And those are questions that are not easy or obvious,” says Benson.

The feminist collective that founded the platform is made up of Benson, Ahmad and their colleague Hana Morgenstern. Ahmad is an assistant professor at the London School of Economics, Benson lectures history at the University of the Western Cape (UWC) and Morgenstern is a lecturer in postcolonial and Middle East literature at the University of Cambridge.

Their shared work as activists brought them together. Ahmad was studying at UWC, where she met Benson. She had worked as a journalist for many years, founding a magazine called Tanqeed, and was involved in political organising around state violence in Pakistan. Benson’s work mobilises for public services and organised resistance to forced removals, housing, water and educational struggles, while Morgenstern focuses on communist party magazines in pre-partition Palestine. It is their Left-focused, progressive politics that motivates their Revolutionary Papers collaboration.

Covid rethink

In 2018, the team imagined hosting a conference after receiving a funding grant. But when the pandemic intervened, the idea went back into incubation where it grew into a fully fledged project and website.

Unlike many other digital archives, Revolutionary Papers is not aiming to create a trove of content that may become unmanageable or difficult to navigate. Rather, their approach is simple. Each paper is documented by year, language, region and theme with a brief synopsis.

The collective then provides meaningful engagement through what it calls Teaching Tools. These take an in-depth look at select papers, give insight on ways to dig deeper into the journals and unravel the political context of each publication.

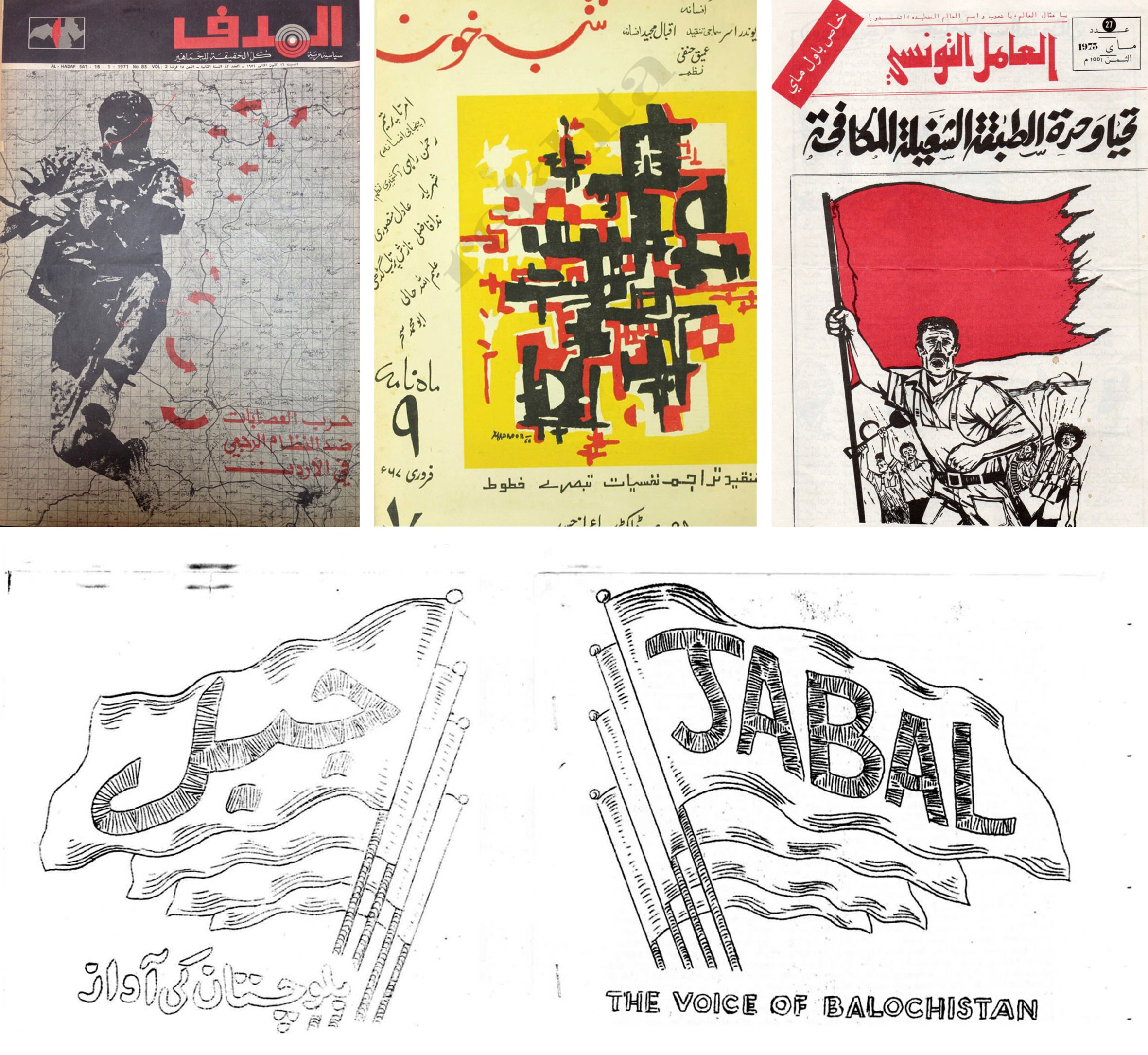

Jabal, The Voice of Balochistan, for instance, is an underground bulletin that was published in English and Urdu between 1973 and 1977. A group of urban Marxist-Leninists from outside the province who were allied with the Balochistan People’s Liberation Front – the movement that launched an insurgency against the central Pakistani government – created it.

Ahmad unpacks the history and context of Jabal and her research is beautifully illuminated by the zine’s text. The publication also features hand-drawn illustrations of fighters in the mountains. Importantly, these tools also invite input from those directly involved with these struggles. For instance, Ahmad’s co-author Mir Mohammad Ali Talpur was involved with the distribution of Jabal in the 1970s.

Crossing boundaries

The Teaching Tools are about the politics of using this material. “How do you take these texts and then put them into conversation with what’s going on now?” Benson asks. Demonstrating this, for Mapping the Social Lives of the Namibian Review she collaborated with scholar and musician Asher Gamedze and performer and writer Nashilongweshipwe Mushaandja while including insights from social movements, artists and high school and university students.

“We’ve talked a lot as a group about the importance of this project crossing a lot of boundaries. So being transgressive in various ways, crossing academia-activist boundaries, crossing the university walls, crossing also regional boundaries,” says Ahmad. “There’s a lot of talk about Global South stuff, but very little attempt to actually have these different regions really speak to each other.”

The ethics of archiving is another important matter. “There’s a lot of really contentious stuff around archives like this,” says Ahmad, referencing the way archives are collected and centralised physically, or collected from one country but stored in another.

“What we want to do is be quite purposeful … There’s this tendency with social media in a TikTok-ish kind of way, where you just show an image and it’s like fetishism of the anti-colonial image, but you don’t know what the history is or what the politics are. So we want to counteract that with the teachings and continue developing them,” she adds.

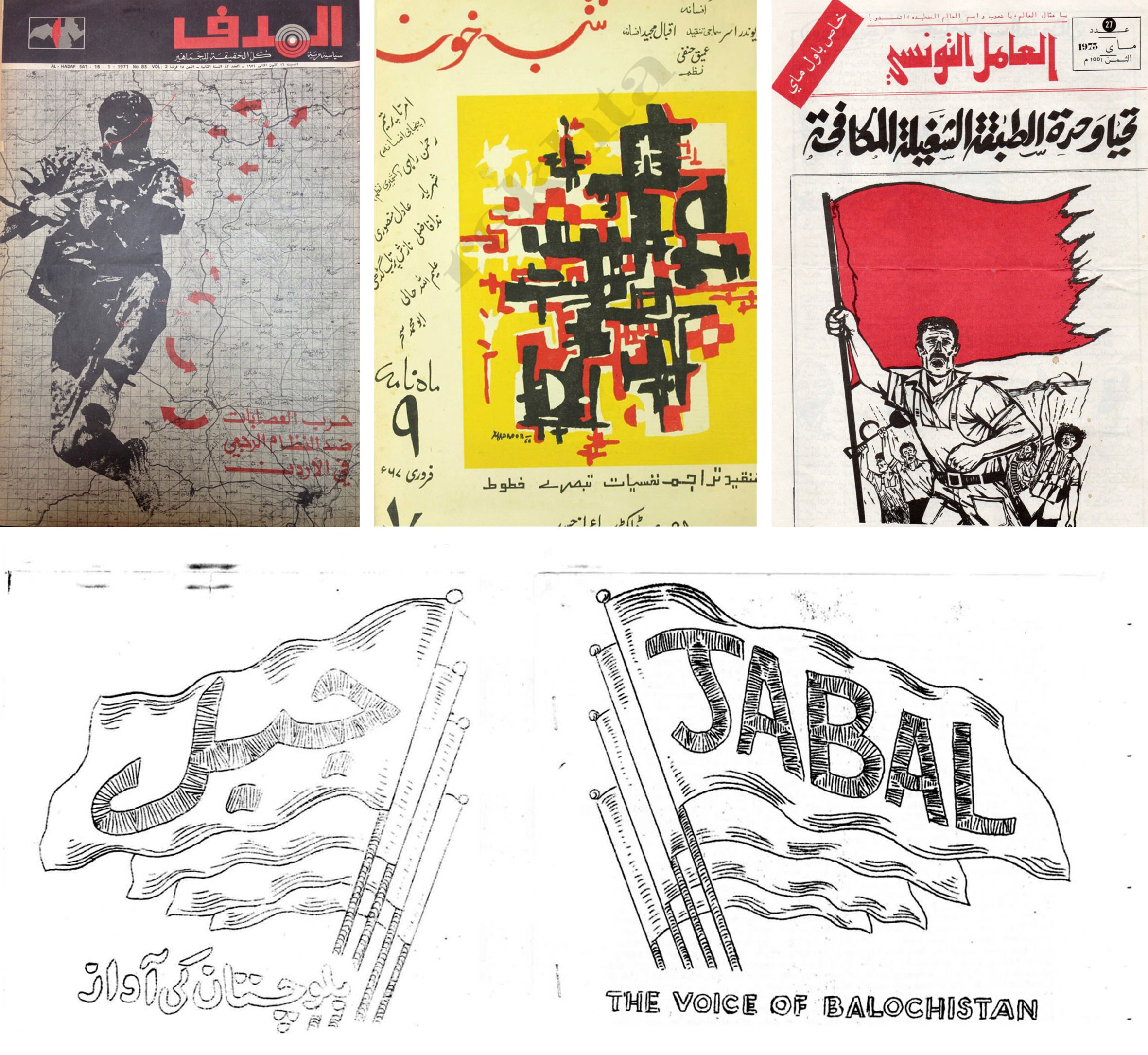

After being pushed back two years, the conference finally took place at the end of April over three days at the Salt River Community House in Cape Town. Its focus was various periodicals, examined in panel discussions with presenters from all over the world.

On the first night, art and music featured as an extension of the papers. This included a photographic exhibition called Quiet Dog Bite Hard: Clandestine Networks of Revolutionary Papers curated by Phokeng Setai, sonic lectures by Nombuso Mathibela and Michael Bhatch, and songs by Soundz of the South and Sara Kazmi that focused on protest music from South Africa and South Asia, respectively. The Surplus bookstore, Chimurenga magazine, The Interim People’s Library and Pathways to Free Education were present in the foyer.

‘The old Left’

“It was really like a big reunion,” says Benson. “It was the old Left in terms of our mentors, people from the underground from the 1970s and 1980s. There were fallists, artists, current activists, housing assembly activists, water activists and academics.”

The conference was an affirmation and further motivation for the team, realising the amount of material available, acknowledging the people who are “living, walking archives” and finding that there is an audience for this kind of work. “It exceeded my expectations in that we had short presentations but long conversations,” says Benson. “And I felt people were really listening to each other. I learnt so much.”

While the platform’s roots are in academia, the intention is to be a practical education and research tool for scholars, organisers and movements. Revolutionary Papers currently hosts rare publications from Kenya, Libya, Oman, Ghana, Ethiopia, Tunisia, Haiti and the Caribbean among others.

The collective is holding steadfast to its aim of archiving such papers not only as images but with meaningful context and ways to learn from them. Its members are also looking beyond periodicals, to manifestos and posters. For now, the project involves more than 40 university-based researchers, editors, archivists and movement organisers from around the world. “Our dream is to collaborate with very grounded and present archives that maybe don’t have all the funding,” says Ahmad.

Now that their first conference is over and a substantial number of journals have been archived, the first phase of the project is complete. Some of the existing Teaching Tools on the website will be translated, and plans include collaborations with community archives, libraries, collectives and authors from around the world.

“I really think that history is a call and response. And if it’s not activated in the present, it doesn’t mean anything. It will sit in a book that will get lost forever,” says Benson.

Correction 1 June 2022: This article has been corrected to reflect that the conference focused on various periodicals from around the world – and not solely African periodicals.