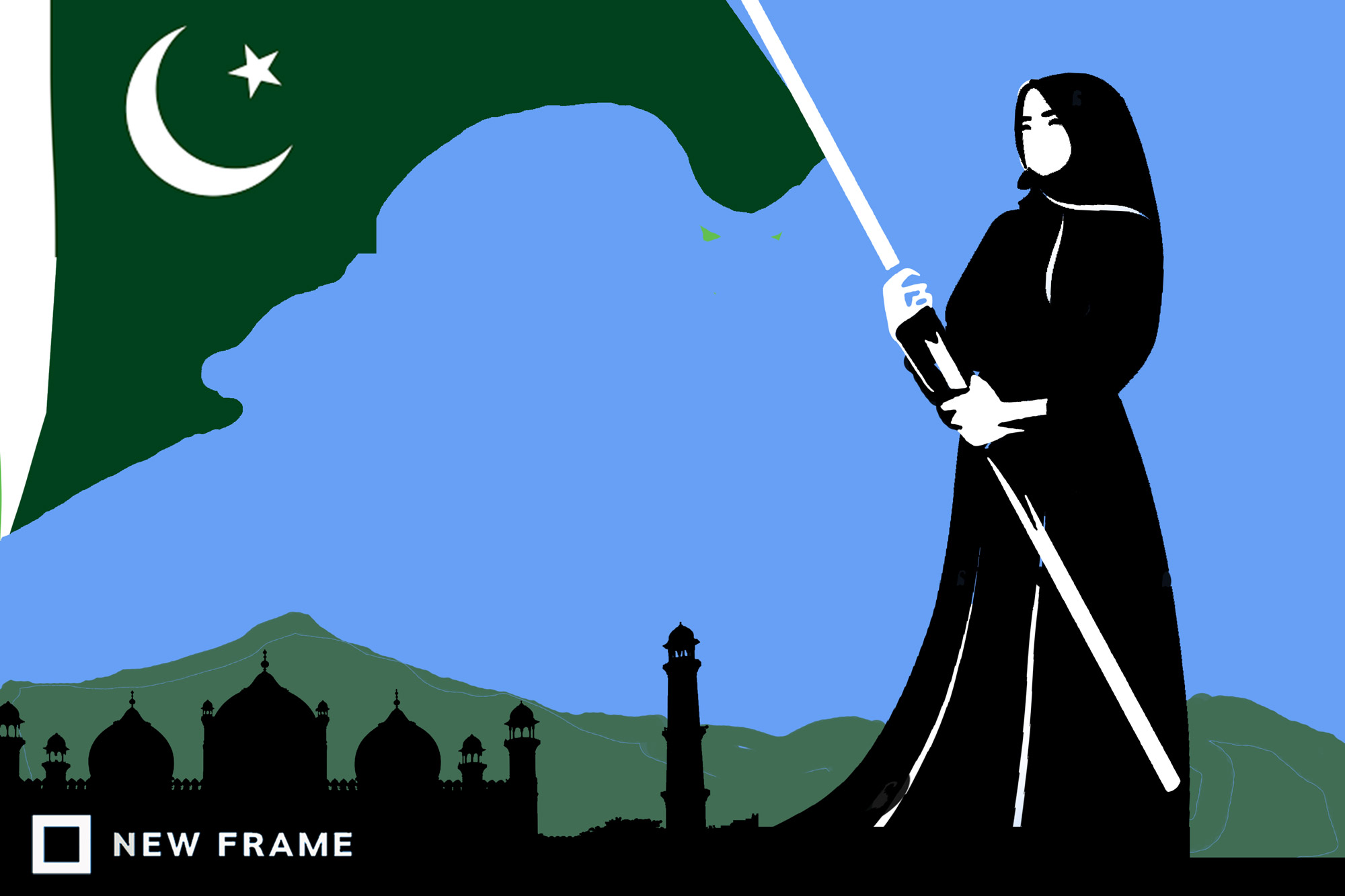

Pakistan’s rising feminist movement

Collective action is shaking up the male-dominated social order in the Muslim-majority nation and rewriting the narratives around gender-based violence, body politics, sexuality and consent.

Author:

15 March 2022

A new, assertive feminist movement has swept Pakistan in the past five years. Led by a younger generation of women, it is confronting entrenched patriarchy in the country and demanding radical reforms to protect the rights of other marginalised communities and gender minorities.

What began as an annual march to observe International Women’s Day on 8 March has evolved into a sustained campaign for social, political, economic and judicial reform. This iteration of Pakistani women’s rights amplifies voices and raises awareness through rallies in major cities including Karachi, Lahore and Islamabad. It makes extensive use of digital platforms for wider mobilisation and uses graphic posters and placards, performance arts, poetry and songs to advocate for different conceptions of femininity.

Related article:

Pakistan’s Aurat March, or Women’s March, was first organised in the business city of Karachi in 2018 to highlight the problems women face in the country. The march came about after feminist collectives and women’s rights organisations – such as the Women Democratic Front and the Women’s Action Forum – established a non-hierarchical steering committee, which is not affiliated with any social or political outfits, under the banner Hum Aurtein (We the Women).

The movement combines online and offline action, mobilising women from different backgrounds through social media campaigns using funds generated largely through crowdsourcing.

The city chapters release a declaration of demands every year on social media that reflects the theme of that year’s procession.

A judicial overhaul

The movement’s initial demands were an end to everyday violence against women, non-binary people and religious minorities; economic justice through the implementation of labour laws and the recognition of domestic work as unpaid labour; reproductive justice for women, non-binary people and all sexual identities; and environmental justice, including better access to water and land and an end to corporate exploitation.

The demands this year are for radical and comprehensive structural changes to Pakistan’s judicial system. The movement wants to replace the “superficial” gender representation through mere numbers to ensure housing, healthcare, economic and psychosocial support for victims of violence, as well as more funding for survivor-centric welfare institutions.

The theme of the Aurat March’s 2022 manifesto is Asal Insaaf, or Reimagining Justice. Instead of short-term fixes such as capital punishment and chemical castration, it calls for systemic reforms that prevent patriarchal violence. “Over the past year, like the years before it, we were exposed to violence: violence in the form of the pandemic, violence due to state policies and negligence, violence at home and violence in the streets,” says the Aurat March Lahore Manifesto.

Related article:

The manifesto stresses the need to create a “culture of care” that goes beyond the individual and in which communities support each other rather than blame the victims. The organisers consulted relevant communities – families who have experienced enforced disappearances, domestic workers, survivors of sexual violence and religious minorities – to draft the manifesto.

The younger generation is looking for alternative, feminist futures. “This exercise in reimagining is necessary because in our five years of organising we have come to the conclusion that women, trans, khwaja sira [gender-ambiguous] and non-binary individuals have no confidence in the legal system’s ability to provide emancipation,” it says.

Shockingly high numbers

Pakistan is ranked 153 out of 156 nations in the World Economic Forum’s 2021 Global Gender Gap Report, ahead of only war-torn Iraq, Yemen and Afghanistan. According to the country’s Human Rights Commission and the Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences, 90% of women have experienced some form of domestic violence at the hands of their husbands or families, while 47% of married women have experienced sexual abuse, particularly rape. Pakistan is the sixth most dangerous country in the world for women, according to the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

Women have a 22% lower literacy rate than men, make up just 22% of the labour force and receive only 18% of the country’s labour revenue. Women account for only 5% of senior leadership positions in the economy.

Related article:

Afiya Shehrbano Zia, a feminist scholar who has written about women’s sexuality and body politics in Pakistan, says the Aurat March’s two main contributions to women’s movements in Pakistan have been the rise of a young leadership and a rude breaking of the silence around sexuality. “It has done so in bold, creative and voluntary ways rather than being politically motivated or project-driven,” she says.

Other academics have drawn a similar conclusion. They say Pakistani feminists regard the Aurat March as a vehicle for focusing on women’s issues, bringing the topic of women’s oppression into the public realm and including voices from different sectors of society: urban, rural, working class, housewives, young and old, artists, thinkers, etc.

“It represents all ideologies of feminism: liberals demanding personal liberties, welfare and legal provisions; radical feminists who want to break the shackles of patriarchy; and socialist feminists seeking freedom from capitalism and patriarchy,” write scholars Syeda Mujeeba Batool and Aisha Anees Malik.

Violent opposition

Opposition to the Aurat March has risen in parallel with its popularity and influence, labelling it Westernised, anti-Islamic and anti-national. March organisers and participants face persistent misrepresentation, blasphemy accusations and threats from the ruling establishment and orthodox elements of society.

Some detractors allege that marchers are elitists who reject grassroots communities and advocate for Western values. Others see campaigners as a foreign-funded threat to Pakistan’s cultural beliefs. The first two Aurat Marches garnered harsh criticism and online abuse of the attendees, who were chastised for using poster slogans that contradicted Pakistani culture, values and religion. Some counter-protesters at the Haya March (Modesty March) in March 2020 threw stones at Aurat March participants. Some of the organisers have received threats of violence, death and rape.

Notable slogans from the march that are the focus of criticism, having been widely adopted, are mera jism meri marzi (my body my choice), khana khud garm karo (warm up your food yourself), mein awaara, mein baddchalan (I loiter, I’m characterless), “divorced and happy” and “anything you can do, I do while bleeding”.

Pakistan’s Federal Minister for Religious and Minority Affairs Noorul Haq Qadri wrote to Prime Minister Imran Khan in February asking him to ban the Aurat March nationwide. He suggested that 8 March be observed as International Hijab Day. Earlier, religious outfit Jamiat Ulema-i-Islam-Fazl (JUI-F) openly threatened to stop the march by using “batons”.

Related article:

The high courts in Islamabad and Lahore dismissed petitions to ban the march last year, saying the right to assemble peacefully is guaranteed in the Constitution.

Many say the patriarchal backlash proves that Pakistani women’s efforts to regain their agency are deflating bloated, misogynistic male egos. Journalist Durdana Najam writes that what Pakistan witnessed at the 2019 Aurat March was different to other women’s marches. It was bold and radical and the slogans in particular unsettled many. “The jarring reality of women crossing all bars to bring down the barriers between them and their male counterparts was not something Pakistan had the appetite to digest.”

Although wider Pakistani society has praised the Aurat March highly, Zia says it has also been subjected to critical scrutiny, including by other feminist scholars. She says the first Aurat March was criticised in 2018 for its disengagement with the state and ambivalence over the role of religion and reliance on social media rather than political purpose.

Such criticism was further highlighted in a 2020 study by scholars Rubina Saigol and Nida Usman Chaudhary, who pointed out historic tensions in the campaign. These included core concerns over political goals, issues of generational differences and the inclusion of themes of sexual orientation.